Chapter 6.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 6.2

Hebrew-Yiddish language question

The Hebrew language was mostly written and used for rabbinic correspondence, court decisions, and community regulations, as well as for works dealing with theological and philosophical questions. In printed form, such Hebrew texts were called sifrei kodesh (holy books). With the rise of the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) in the early nineteenth century, secular books in Hebrew began to appear, including original works in the sciences and philosophy, translations of secular literary works, newspapers, and modern poetry and prose. Even though Hebrew was a written language, literacy in that medium was limited. In other words, many Jews might be able to read and understand the texts, but they could not write in Hebrew. The latter skill was for the most part limited to the rabbinic elite. Although biblical Hebrew was the basis for traditional Jewish education, it was not taught according to grammatical rules. Instead, a melamed, elementary school teacher, provided biblical word combinations and sentences with Yiddish explanations, in order that students would memorize each biblical verse together with a canonical interpretation (pshat — plain meaning). Thus, children absorbed Hebrew words with an entire set of connotations and semantic field stemming from the rabbinic tradition, but with the corresponding interpretations in Yiddish.

One of the leaders of the Jewish Enlightenment in eastern Europe, Yitshak Ber Levinzon from Kremenets, sharply criticized this practice. He argued that Hebrew was a language suitable for any kind of discourse. Moreover, as a language of prestige, Hebrew should be the vehicle for creating an enlightened Jewish culture based on general education. Levinzon's major work on this subject, Teudah be-Yisrael (Testimony for the Jews, 1827), was published with the support of the tsarist Russian government. This is because Jewish printers at the time resisted publishing the works of Enlightenment/Haskalah scholars, which they labeled with the derogatory diminutive Yiddish word bikhelekh (little books).

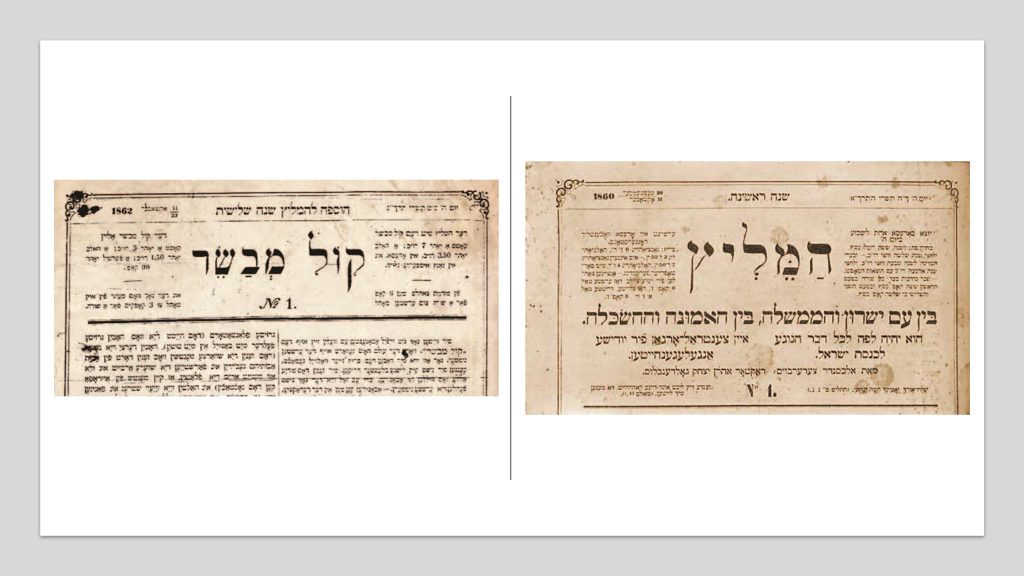

Despite skepticism and even opposition from traditionalist circles, Hebrew slowly moved to the forefront of secular Jewish life, beginning with some tentative efforts in the 1860s, when Alexander Zederbaum launched in Odessa Ha-Melits (The Advocate, 1860–1904), the first Hebrew newspaper in the Russian Empire. It was not until 1880s, however, that the new Hebrew revival really took off. At that time, two decades before Zionism came into being, various groups of Odessa-based intellectuals had already begun speaking Hebrew on a regular basis, writing essays in Hebrew on various modern issues, and presenting Hebrew studies as an integral part of the Jewish diasporan spiritual revival. These groups, called Bnei Moshe (Sons of Moses), Hibbat Zion, and Ahavat Zion (the latter both meaning Love of Zion), had as their most influential figures the critical thinker Ahad ha-Am (pseudonym of Asher Ginzberg) and the poet Hayim Nahman Bialik. Together with the Odessa-based publishing house Moriah, they championed the revival of Hebrew as the desired secular language not only for the Jews of Europe but also for their future homeland — the Land of Israel. It is in this context that the Ukrainian-born Ahad ha-Am subsequently became somewhat of a cult figure in the pantheon of the founding fathers of modern Israeli culture.

The secular promoters of Hebrew as well as the tsarist authorities looked down on Yiddish as a ghettoized mishmash and obstacle on the road to Jewish assimilation into the great and prestigious Russian culture. Therefore, both the Jewish Enlighteners and imperial Russian government, although for different reasons, denied Yiddish the status of a language, dubbing it officially a jargon. Yet even the opponents of Yiddish realized that they needed to resort to that very language if they hoped to push Jews toward cultural reforms. It was with this in mind that Alexander Zederbaum issued in Odessa the first Yiddish newspaper, Kol Mevaser (The Herald, 1862–1872). Written mostly in Ukrainian Yiddish, Zederbaum's newspaper opposed russification, which at the time the tsarist regime was actively promoting. Hence, the authorities discouraged the use of Yiddish, as they did Ukrainian, and outlawed Yiddish-language theatrical performances.

With the rise of various Jewish political parties in the Russian Empire, party leaders ranging from Bundists to Folkists to Zionists were forced by practical reality to address their followers in Yiddish, the mother tongue of 97 percent of the empire's Jews. Yiddish-language newspapers published in Russian-ruled Poland and Lithuania, with a circulation in the hundreds of thousands, found avid readers among Ukrainian Jews. For the socialist-oriented Bundists, Yiddish as the language of the uneducated and poor Jewish proletarian masses was not only the medium of propaganda but also the cornerstone of their Marxist ideology. The Bundists considered Hebrew the language of the oppressors, whether the Jewish bourgeoisie, religious bigots, or Jewish nationalists, all of whom were seen as class enemies of the Jewish proletariat. Hence, while the Zionists modernized Hebrew, transforming it into the language of a renewed Jewish people and adapting it for the new circumstances after emigration to the Holy Land, the Bundists proclaimed Yiddish as the respectable "language of the people" in the diaspora. The politicization of this new, secular Yiddish was manifest in the work of the Czernowitz (Chernivtsi) Language Conference of 1908, the first of its type, which brought together writers and educators, Bundists and Zionists, and prominent cultural figures — all of whom noted the growing popularity of Hebrew among Jewish youth while at the same time being concerned about the deprecation of Yiddish within the ruling circles of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. The Czernowitz conference did call for support of Yiddish literary, educational, and cultural endeavors, but in the end decided to proclaim Yiddish as a Jewish, not the Jewish national language.

The various forms of acculturation that characterized Jewish life in Ukrainian lands throughout the nineteenth century contributed to the politicization of language. In essence, language become an instrument to manifest, shape, and modify new forms of loyalty, whether it be primarily to the state or to one's own people. For Jews in Austria-Hungary, the choice, depending on region, could be Polish, German, Hungarian, Hebrew, Yiddish, or some combination of these rather distinct languages.

The Jews in Austrian Bukovina preferred the Habsburg imperial language, German, and therefore remained on the margins of the Hebrew and Yiddish revival of the second half of the nineteenth century. While a Hebrew printing press was established in Chernivtsi as early as 1835, it produced mostly traditional Judaic classical texts for religious study. Only after the 1870s did it begin to publish secular works in Yiddish and Hebrew. The Israelite German-language Jewish schools in Suceava (today in Romania) and Chernivtsi may have offered Hebrew classes as an obligatory part of the curriculum, but most publications across the political spectrum — Zionist, Marxist-socialist, national-assimilationist — were in German, as were the wide range of local Jewish newspapers, among which were the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums (General Jewish Newspaper), the Jüdische Volksrat (Jewish People's Council), and the Czernowitzer Tagblatt (Chernivtsi Daily Paper).

The situation was more complex in Austrian Galicia. There many Jews felt themselves part of the Polish nationality and chose to read the Polish-language newspapers Ojczyzna (Fatherland) and Przyszłość (The Future). Those Galician Jews who wished to emphasize loyalty to the Habsburg rulers used German, as in the newspaper Der Israelit (The Israelite), first published in Hebrew transliteration and later in German Gothic script. On the other hand, publications that were aimed at a wider strata of the Jewish population and that promoted national-democratic ideas used Yiddish, examples being the early-twentieth-century daily newspapers Togblat (Daily Paper) and Der tog (The Day) and the Marxist-oriented Der sotsial-demokrat (The Social-Democrat). There were also Hebrew-language newspapers, but these were mostly for a male audience of well-educated elites, including three weeklies: Ha-Ivri (The Jew), in Brody; Ha-Mevaser (The Herald), in Lviv; and the Hasidic Mahazikei ha-dat (Guardians of Faith), in Belz. In addition, dozens of Galician and Bukovinian Jewish writers regularly contributed to the Yiddish-language press published in Warsaw in the Russian Empire.

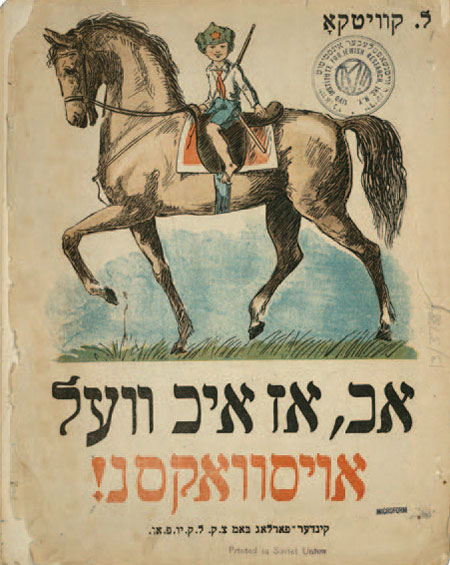

Later, under Soviet rule, the indigenization campaign of the 1920s declared Yiddish to be the appropriate language of the Jewish masses. This campaign led to the establishment of village councils (soviets), based on the nationality principle, where local administration, courts, and education were conducted in the language of the socialist Jewish people — Yiddish. At the same time, the campaign tried to get rid of Hebrew, since the regime considered it a symbol of the bourgeois, religious, and nationalistic class enemy. The Soviet regime also encouraged the further reform and standardization of Yiddish, now considered as the genuine language of the proletarian Jewish masses. Ukrainian-based Soviet linguists (Nokhem Shtif and Elye Spivak) continued the work of the Berdychiv-born folklorist Noah Pryłucki/ Noyekh Prilutski, who already before World War I had laid the linguistic foundations for the study of the Volhynia variant of Ukrainian Yiddish.

The Soviet regime transformed language into a political matter. Almost all the basic words of Hebrew origin were declared linguistic "class enemies" and banished from Yiddish, to be replaced by words with German or Russian roots. A new phonetic spelling was introduced following the principle: write as people speak. Consequently, in those cases where a word proved impossible to banish, it was retained but spelled in such a way that its biblical or Talmudic origin would not be recognizable. Finally, hundreds of neologisms were introduced into Yiddish in order to convey the new Soviet reality, such as oporosn sikh (to farrow) or kolvirt (collective farm). Soviet Yiddish became the language for newspapers, schools and textbooks, translations, and the theater. Soviet enthusiasm for the Yiddish language began to waver during the crackdown on bourgeois-nationalism in the early 1930s.

After World War II and the destruction of the Holocaust, Jews were faced with the closure of practically all Yiddish venues in the Soviet Union. That development, combined with the rampant antisemitic campaigns of the 1950s and increased russification in various spheres of life, left Ukraine's Jews without a single Yiddish-language publication for cultural expression. All that remained was the Moscow-based literary journal Sovetish Heymland (1961–91), where some Ukrainian Yiddish writers who survived the Holocaust and the anti-cosmopolitan campaign of the late 1940s and early 1950s began to publish.

At present, the language situation among Jews in Ukraine is very similar to that in Israel, the United States, and Canada. The rabbinic leaders of Orthodox (Litvak) and ultra-Orthodox (Hasidic) orientation who live in Ukraine permanently use Yiddish for oral communication at home and only sporadically for teaching. On the other hand, Yiddish has entered the secular classroom at a number of higher educational establishments, including the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy National University in Kyiv and the Center for Urban History in Lviv, where it has become part of the Jewish studies curriculum.

Most Ukrainian Jews know several Yiddish words and some remember colloquial phraseological expressions or even recall a Yiddish song, but they do not speak the language. Recent ethnographic expeditions to Podolia discovered that there were still some people who, if asked, could speak Yiddish, the language of their parents, who were part of the pre-World War II Jewish community of Ukraine. The rarity of such examples simply proves that, as a spoken language, Yiddish has almost completely disappeared from public life in Ukraine, even if some elements are retained in popular culture and memory. We have seen how the attempts to revive Yiddish during the last years of the Soviet Union lasted in Ukraine only until the early 1990s. Since then, those efforts have been replaced by much more consistent programs to revive Hebrew, a language of particular importance for those who decided to emigrate to Israel.

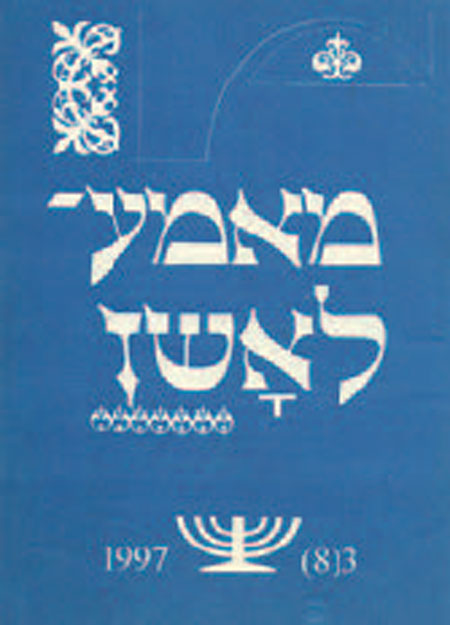

It is therefore no surprise that today Hebrew has became the most popular language of instruction for adult Jewish education in Ukraine. Hebrew-language dictionaries, textbooks, and teaching aids published predominantly in Israel are available and often distributed for free. Also, in post-Soviet independent Ukraine, Hebrew holy books containing traditional texts (sifrei kodesh) produced abroad were brought in by the thousands by newly arrived rabbinic leaders and missionary organizations. A few new Jewish newspapers in Russian and Ukrainian have also included Hebrew texts from time to time for educational purposes. The only periodical with a significant portion of its material in Yiddish is the Odessa-based quarterly journal Mameloshn (Mother Tongue), which since its founding in 1995 has had a limited yet dedicated audience. In the second half of the 1990s, publishers in Chernivtsi issued two Yiddish collections of prose works by the Bukovina Yiddish writer Yoysef Burg, considered "one of the last Yiddish writers of Eastern Europe." It was, however, in the realm of Ukraine's pop culture that Jewish themes have found a particularly receptive audience. This has occurred through performers of klezmer music, who include in their repertoire songs in Yiddish that provide at least some insight into the vanished world of Ukraine's Jewish culture.

Manuscripts and book printing

Slavonic and Cyrillic

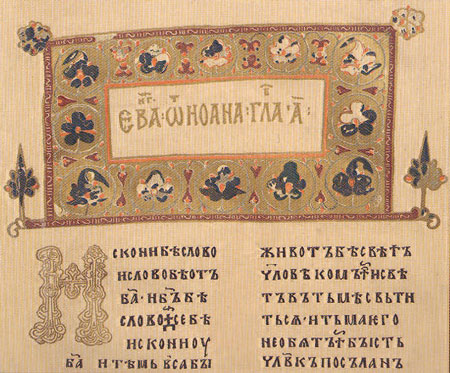

As in other parts of Europe, the earliest centers for the production of the written word in Ukraine were Eastern Christian monasteries, one of whose main goals was to prepare handwritten religious texts for the church. The first important site for manuscript production in Ukraine was initiated by the state through the person of the grand prince of Kievan Rus', Yaroslav I ("the Wise"). Known as "a lover of books," Yaroslav assured that a part of the cathedral church complex at the St Sophia in Kyiv (built in the 1040s) would have a scriptorium (copying center) for the creation of books. Other monasteries throughout Ukraine, the Monastery of the Caves (Pecherska Lavra) in Kyiv being the most prominent, functioned as centers of manuscript production throughout the medieval period. It was at such monasteries that monks created the oldest surviving dated Slavonic book, the elegantly illustrated Ostromir Gospel (1056–57), and the oldest East Slavic historical account, the Rus' Primary Chronicle (begun in the 1040s).

About a half-century after printing with movable type was introduced in Europe (1450s) by Johann Gutenberg, the first religious books intended for the Eastern Orthodox in Ukrainian and Belarusan lands were produced with the new technology. Initially, they were printed outside Ukraine by the founders of Slavonic printing, Schweipoldt Fiol in the 1480s in Cracow and Francis Skoryna in the second decade of the sixteenth century in Prague. It was not until the 1570s that the first printing shop for books in the Cyrillic alphabet was established in Ukraine, by Ivan Fedorov in Lviv. A decade later, Fedorov moved to the estate of Prince Kostyantyn Ostrozkyi, where he and his successors printed numerous books in Ukraine's first center of printing, the small town of Ostroh in Volhynia. Later, in the eighteenth century, the same small building in Ostroh that had housed the Slavonic printing shop was used by the Jewish printer Kliorfain.

The earliest printers faced a problem that remained a challenge for many of their successors as well: how to secure Cyrillic typefaces for printing shops in Ukrainian lands which at the time were ruled by a state, Poland-Lithuania, where the Roman, or Latin, alphabet was the norm. The situation became more complex at the beginning of the eighteenth century, when Tsar Peter I of Muscovy/ Russia, which by then ruled at least half of Ukraine, introduced a revised Cyrillic alphabet called the civil script (hrazhdanka), whose letters were rendered in a simpler, more easy-to-read form than the more elaborate and stylized letters of the traditional Cyrillic alphabet. This meant that, from then until well into the twentieth century, printers had to be equipped to produce books for Ukrainian readers in the "old" Cyrillic script (mostly Church Slavonic religious texts) and the "new" Cyrillic civil script, which eventually became the standard for all publications other than church books.

It is perhaps not surprising that monasteries, which were already earning a good portion of their income by producing handwritten manuscripts, quickly adopted the new technology of printing with movable type. Among the most noted printing centers was the older Monastery of Caves in Kyiv from the early seventeenth century, and the newer Dormition Monastery at Pochayiv in Volhynia, whose printing tradition has stretched unbroken from its sixteenth-century beginnings in the homeland until the present in the United States, that is, after the monks were exiled by the Soviets in 1944 and re-established printing operations in their new home at Jordanville in upstate New York.

Influential books in Ukrainian

Printed books have always had first and foremost a functional purpose — to convey information to the reader. But they may also have aesthetic value as examples in the art of printing and design; or, because of their content, as symbols of pride and patriotism, especially among stateless peoples like Ukrainians who for centuries were engaged in a struggle to prove their very existence as distinct nationalities.

Among the first influential printed books destined for a Ukrainian reading public were those that were religious in character, such as the first complete edition of the Bible in Church Slavonic, known as the Ostroh Bible (1581) after the town in which it was printed; and the Gospel of Peresopnytsya (1555–61), noted for its extensive use of Ukrainian vernacular speech, something quite rare before the nineteenth century. It is a first edition of the latter that is used during presidential swearing-in ceremonies in post-1991 independent Ukraine. Another book of a special significance during this early period was secular in nature, the Sinopsis (1674), attributed to an Orthodox cleric Inokentii Gizel. Originally printed in Kyiv and subsequently reprinted thirty times until the early nineteenth century, it became a kind of basic history textbook in schools throughout the Russian Empire. The reason for its popularity and acceptance among the ruling secular and religious authorities was because it was the first work to present in a systematic manner the view that Muscovy and later the Russian Empire were the successor states to Kievan Rus', and that, therefore, they had a rightful claim to all lands (Belarus, Ukraine, as well as European Russia) which once were part of that medieval entity.

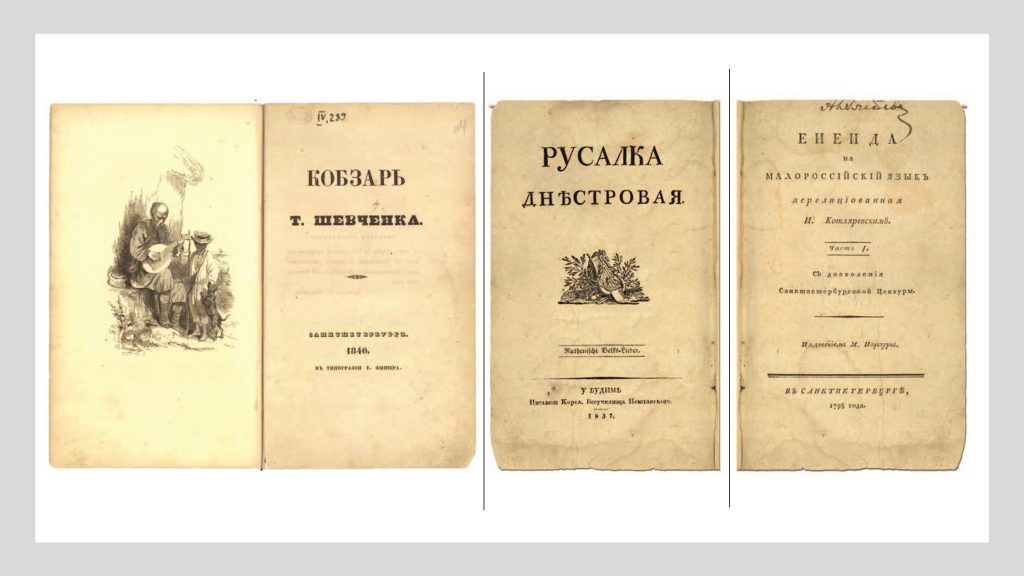

Books were especially important to the national awakenings of the nineteenth century. Among those that since their first appearance became signposts in the evolution of Ukrainian literature as well as the embodiment of ethnic Ukrainian identity were: Eneyida (Aneida, 1798) by Ivan Kotlyarevskyi, the first work of modern Ukrainian literature written in the vernacular Ukrainian; Kobzar (The Minstrel, 1840) and Haidamaky (The Haidamaks, 1841), both works of poetry which created the reputation of Taras Shevchenko as the national bard of Ukraine; and Rusalka dnistrovaya (The Nymph of the Dniester, 1837), considered the first book intended for the Ruthenians/Ukrainians of Galicia that was written in the vernacular language — and in the "modern" Cyrillic script, hrazhdanka.

Publishing and Ukrainian culture

The number of copies of first editions and reprintings of Ukrainian-language books has had important social and national implications. At least until the age of the Internet, books (and newspapers) were the main instruments through which the Ukrainian language and national identity was preserved and promoted. For example, in the relatively tolerant political atmosphere of late-nineteenth-century Habsburg-ruled Austrian Galicia, community-based and privately funded Ruthenian cultural and civic organizations made every effort to produce their titles with the largest printings possible, with some books having print-runs up to 100,000 copies.

In Soviet Ukraine, where the publishing industry was exclusively in the hands of the state, the number of copies of any given title reflected as much political as economic criteria. In other words, when the Soviet government was favorably inclined toward Ukrainian cultural aspirations, as during the 1920s, the print-runs of Ukrainian titles were large enough (sometimes in the millions) to fulfill the needs of the country's reading public, whether or not they were ethnic Ukrainians. Some titles, such as the collected writings of the classics of Soviet Marxist thought — Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin — were published in Ukrainian translation in print-runs of several hundred thousand, even though they usually sat unread collecting dust on the shelves of libraries, large and small, in every city, town, village, school, factory, and agricultural cooperative recreational center. To this day, scholars writing about the nationality policy of the former Soviet Ukraine make use of statistics on print-runs of books in an effort to gauge state policy toward its various nationalities. Print-runs of books are no less an issue of concern to policy-makers and nationality-builders in present-day independent Ukraine. For the most part, book publishing today is driven by economic factors. Hence, even though Ukrainian is the state language, the vast majority of books available in any bookstore are in Russian. This is because publishers in Russia are able to finance large printings of popular literature (crime and love stories, technical how- to-do literature, translations from other languages) and dump a portion of their production in Ukraine, where local publishers are simply unable to compete in producing comparable Ukrainian-language editions. Book production, then, remains an important factor in the ongoing struggle to enhance and promote Ukrainian culture and identity.

Jewish manuscripts and early printed books

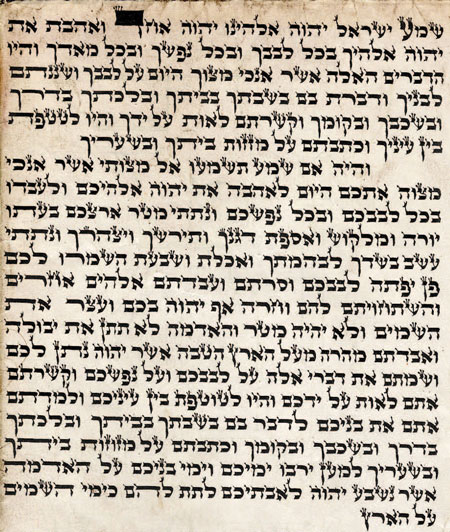

The earliest Hebrew manuscripts used in Ukraine were the Torah scrolls and communal prayer books on parchment or vellum that were brought between the ninth and fourteenth centuries to Crimea by the Jews of Byzantium and to central Ukraine by Ashkenazic Jews from central Europe. Although none of these manuscripts has survived, scholars surmise that Jewish scribes in Crimea used the Aleppo style to write the text of the Pentateuch, while those in Poland-Lithuania used the Ashkenazic style.

Later, in the eighteenth century, there emerged a new style of writing used first and foremost by the Habad Hasidic community. The founding father of the Habad movement (Rabbi Schneur Zalman) linked the shape of letters of the Torah scroll to, and understood them through the prism of, Kabbalah traditions of sanctified letters of the Hebrew alphabet. The so-called scribal style (otiot ha-rav, "letters of the Rabbi") was widely used for Torah-scroll writing in Hasidic communities throughout Ukrainian lands.

Rabbinic books, among the best known being the fifteenth-century commentary of Moshe ben Yaakov of Kyiv on the early medieval mystical work Sefer yetsirah (Book of Creation), were predominantly in Hebrew. Although most Jewish manuscripts composed in Ukraine in late-medieval and early-modern times have not survived, an exception are the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Hebrew-language record books (pinkasim) of Jewish communities and brotherhoods.

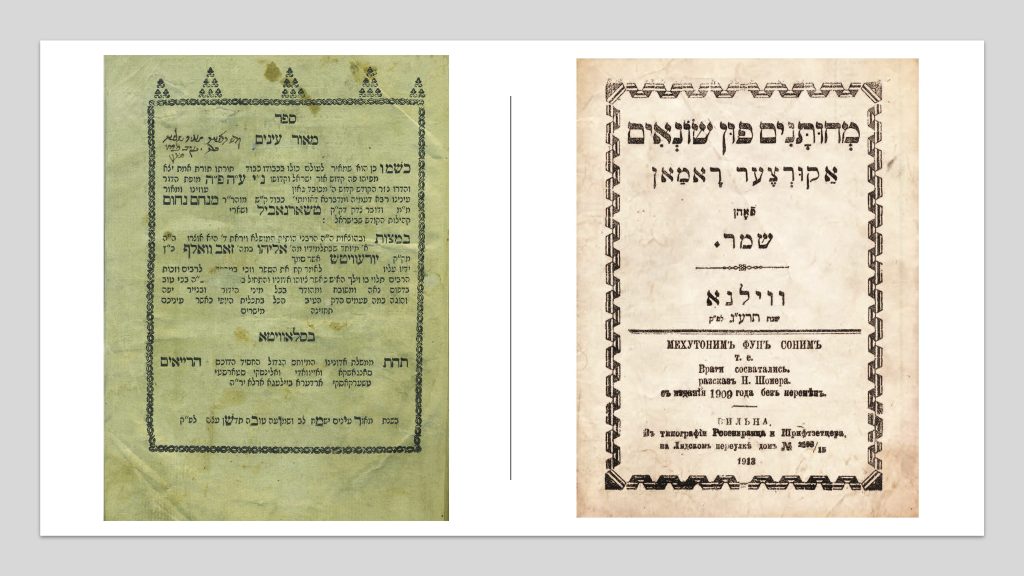

The first European manuscripts written in Yiddish date back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In Ukrainian lands, especially popular were late-eighteenth-century Yiddish-language collections of individual women's prayers (tekhines) and moral tales (maysyos), which quickly made their way into print. Yiddish also appeared sporadically in the record books of the Jewish brotherhoods, although it was rarely used for communal records. The most popular Yiddish composition, Tsene rene, created somewhere near Lublin, was published perhaps as early as 1613 and became the foremost best-seller among the Jews of eastern Europe. Because it was written in Yiddish and emphasized gender roles, the book was particularly appealing to Jewish women and became known as the "women's Bible." The book was therefore issued in more than a hundred editions, adaptations, and reprints produced in various Jewish presses in Ukraine between the early seventeenth and late nineteenth centuries. Printed books in Hebrew and Yiddish began to appear in Ukraine in 1691, following the establishment of a printing press in Zhovkva in Galicia. This printing shop, founded by the Dutch-Jewish printer Uri Fayvesh ben ha-Levi, was one of only three with Hebrew typefaces throughout the entire Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Fayvesh managed very quickly to outdo his competitors, so that by the early eighteenth century his printing press came to dominate the eastern European Jewish book-printing market, producing separate tractates of the Talmud, homiletics, prayer books, and books on Jewish mysticism. Fayvesh's descendants, the Madpis and the Letteris families, founded a number of printing presses throughout Ukraine (Lviv and Sudylkiv) and Poland late in the eighteenth century.

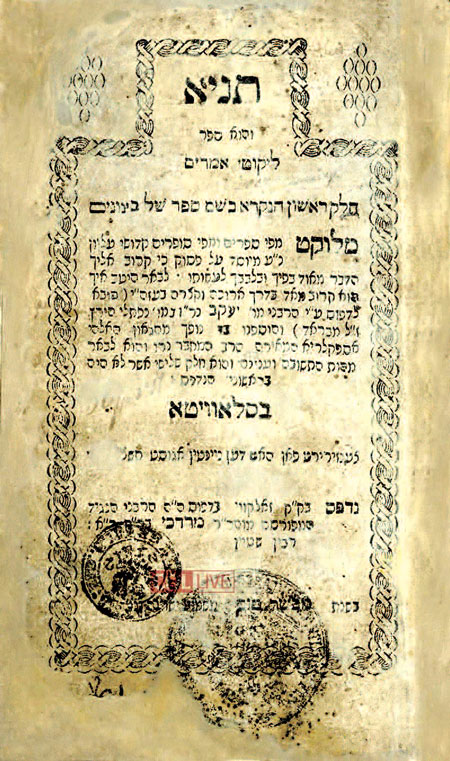

The real explosion of Jewish printing followed the partitions of Poland, when the empress of Russia Catherine II encouraged the establishment of free printing in all new lands that came under her rule. This was a time when the Hasidim in Ukraine were under multiple excommunication bans issued by the Russian Empire's Lithuanian-based Jewish ka- hal. To prove that they were not a marginal group of sectarians but rather at the core of Judaism, the Hasidim responded by establishing several mobile printing presses throughout Ukrainian lands: in Kiev province (Bila Tserkva, Bohuslav), Podolia (Bratslav, Medzhybizh, Mynkivtsi), and Volhynia (Berdychiv, Dubno, Korets, Mezhyrich, Ostroh, Polonne, Slavuta, Sudilkov, Zaslav). These presses published traditional Jewish books endorsed by Hasidic masters (tsadikim). Such activity showed that Hasidism did not dissuade ordinary Jews from the traditional learning of classical Jewish books but, on the contrary, encouraged them to study such books. Aside from works on ethics (musar), the legal aspects of Judaism (halakhah), everyday pietistic behavior (hanhagot), commentaries on the Torah, and Kabbalistic prayer books, they published a hagiography of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov, which appeared in both Hebrew and Yiddish versions.

Among the most influential of the Jewish presses was that of the Shapira brothers in the small Volhynian town of Slavuta. It issued several full editions of the Talmud that encouraged innovative approaches to teaching in nineteenth-century Talmudic academies, as well as prayer books and key Kabbalistic and Hasidic commentaries on various classical books of Judaism.

Publishing industry and Jewish society

Printers were esteemed in traditional Jewish society. In fact, purchasing books in and of itself was broadly conceived as part of a commandment to spread the Torah to the whole world. It is difficult, therefore, to imagine a Jewish household, even a poor one, without a Hebrew book. Hence, it was not uncommon in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ukraine for a poor artisan to have three to four Hebrew holy books (sforim), for a petty merchant or a leaseholder to have from twenty to thirty, a wealthy wholesaler about one hundred, and a rabbi several hundreds. Books were sold unbound, purchased in bulk, and then given to a skillful book-binder, a profession whose widespread nature is reflected in the common Jewish last name, Bukhbinder.

The work of Jewish printing presses in the Russian Empire was disrupted in 1836. As a result of false denunciations, the Slavuta-based Shapiro family of printers was exiled from the Pale of Settlement and all other Jewish printing presses in Ukraine were shut down. Early in the 1840s, however, Tsar Nicholas I allowed a Jewish press to be established in Kyiv, and the Shapira brothers were allowed to return from exile. Instead of Kyiv, they opened a printing shop in Zhytomyr where they employed hundreds of Jewish and non-Jewish workers and published annually between twenty and fifty titles with an average circulation of 2,000 copies per title. The Shapiro printing shop in Zhytomyr had its own paper factory and dominated the Jewish book-printing market in Ukraine until the early 1860s, when Tsar Alexander II issued new regulations that liberalized the press.

By the last third of the nineteenth century, Jewish liberal-minded intellectuals in the Russian Empire realized that the Jewish masses whom they were trying to reach rarely read Hebrew periodicals. They were, however, avid readers of the Yiddish-language Odessa newspaper Kol Mevaser and of publications otherwise dismissively described as shund (trash). Shund was an early example of modern mass culture: cheap soap-opera-style works imitating Russian theatrical dramas and western European, particularly French, "boulevard novels." In an effort to challenge the hegemony of shund (with its hundreds of novels) and to bring their new vision of Jewish culture into Russia's Jewish book market, writers such as Mendele Moykher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem abandoned attempts to write in Hebrew or Russian and instead turned to Yiddish. In fact, the vast majority of writers associated with the origins of modern Yiddish literature and theater were either born or worked in small cities of Ukraine: Starokonstyantyniv, Berdychiv, Zhytomyr, and Vinnytsia.

It was as a result of their efforts that Yiddish secular novels, plays, short stories, and periodicals, all of a high literary standard, slowly but steadily filled the market and changed the standards among Jewish readers in the Russian Empire. The change was most evident in the press. Whereas, for instance, in the 1860s the number of subscribers to the only eastern European Yiddish periodical (Odessa's Kol Mevaser) did not exceed 300, by the first decade of the twentieth century the circulation of daily Yiddish newspapers in Ukrainian lands of the Russian Empire alone exceeded 300,000 copies.

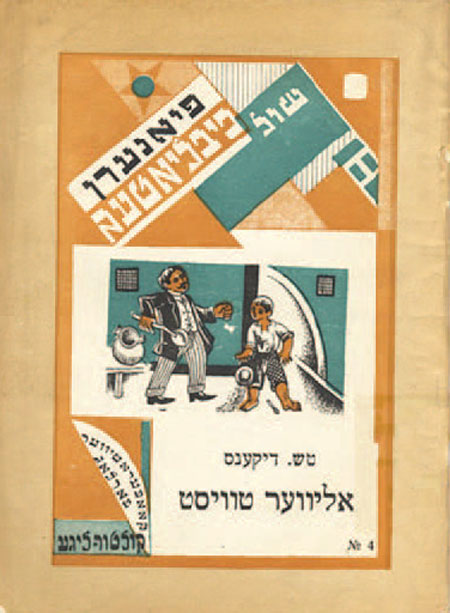

Following the Bolshevik Revolution and the creation of the Soviet Union in what was formerly the Russian Empire, Soviet Ukraine became one of the main centers of the sovietization of Jewish culture. This included reform of the Yiddish language, whose status was enhanced through a wide range of publications. Yiddish printing presses published thousands of copies of world classics — translations from Shakespeare and Cervantes to Dickens and Zola — and throughout the interwar years of Soviet rule dozens of Yiddish books, journals, and newspapers, each with a circulation that often exceeded hundreds of thousands. These publications targeted a broad audience — from lovers of literature and professional teachers to artisans, peasants, and proletarian workers — for whom Yiddish became a vehicle of integration into socialist society. Soviet Ukraine's leading Yiddish periodicals appeared in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odessa.

At the very same time, across the border in former Habsburg-ruled lands by then in interwar Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, there was a Yiddish-language press, although in Polish-ruled Galicia the most popular Jewish periodicals appeared in Polish. Of particular importance for Ukrainian culture in general and for Ukrainian-Jewish relations in particular was Yakov Orenstein (1875–1944), whose prodigiously active publishing house in the Galician town of Kolomyia, and after World War I in Berlin, issued thousands of Ukrainian-language books on a wide range of topics. Orenstein, who called himself "a Ukrainian of Jewish origin," contributed as no one else to Ukrainian book publishing in Austrian- and later Polish-ruled Galicia during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

In Romanian-ruled Bukovina, many Jews, as in Habsburg times, continued to use German, the dominant language of Jewish book publishers as well as the influential Ostjüdische Zeitung (Eastern Jewish Newspaper, 1919–38). There were, however, Bukovinian Jewish publishing houses which produced Yiddish- and Hebrew-language books and newspapers, such as the Yiddish Frayhayt (Freedom) and Tshernovitzer bleter (Chernivtsi Pages), and the Hebrew Ha-Herut (Freedom).

In interwar Czechoslovak-ruled Subcarpathian Rus'/Transcarpathia, Yiddish remained the most popular medium for all socio-political groups, used by, among other publications, the Orthodox weekly Di yidishe tzaytung (The Jewish Newspaper) and the populist Dos yidishe folksblat (The Jewish People's Paper). Even the small Zionist movement in Sub-carpathia published its main periodical Di yidishe shtime (The Jewish Voice) in Yiddish, although it supported the idea of Hebrew as the most appropriate language for Jews.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.