Chapter 7.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 7.1

Literature and theater

Evolution of Ukrainian and Jewish-Ukrainian literature

Linguistic complexity

in the popular mind, literature is usually defined by the language in which it is written. Hence, English literature is in English, French literature is in French, and so on. It is more reasonable, however, to view a literature as something determined not necessarily by its language but rather by the values, experiences, and traditions of the people it reflects or for whom it is written. In fact, for many peoples in Europe, the works that encompass the corpus, or canon, of their respective literatures have often been written in a language that differs from their present-day national language. For example, Beowulf, written in Anglo-Saxon, is considered the earliest work of English literature, works in Persian are part of Turkish literature, and those in Latin dominate the early periods of literary production among Europe's various Romance peoples (French, Spanish, Italians, Catalans) and, for that matter, among Germans, Hungarians, and Poles as well.

It is within this larger European context that the literary traditions of ethnic Ukrainians and of Jews in Ukraine have also been multilingual. Ukrainian literature in the medieval period of Kievan Rus' was written in Church Slavonic. That language in its various local variants continued to be used after Kievan Rus' no longer existed, although during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when most Ukrainian lands were ruled by Poland-Lithuania, many writers used Latin, Polish, and on occasion Greek for literary expression. By the late eighteenth century, Russian became increasingly widespread until it was challenged by the Romantic movement in the early nineteenth century, which gave encouragement to a small group of writers to use a language based on the spoken vernacular of the people, known under its tsarist Russian bureaucratic name, Little Russian, or Ukrainian.

It is from the Romantic period, with its emphasis on language as the defining characteristic of a people, or nationality, that Ukrainian literature came to be associated only with works written in the Ukrainian language. Nevertheless, some Ukrainian authors — understood as those whose works embody the experiences, values, and traditions of ethnic Ukrainians — continued in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to write in Russian as well as in Ukrainian.

Jewish literature in Ukraine is no less multilingual. Like Ukrainians, Jews wrote in a sacred language as well as in the official language of the state where they lived, before eventually adding to the mix a literary form based on the spoken vernacular. Specifically, the sacred language was Hebrew, while the state languages most popular among Jewish writers were Polish and Russian, as well as others in specific historic regions of Ukraine: German, Polish, Hungarian, or Romanian in western Ukraine; and Turkic (written in Hebrew letters) among the Krymchaks and Karaites of Crimea. With the increase of secular literature in the second half of the nineteenth century and the general interest in Jewish national culture, Hebrew became the language of choice for many writers. It was not long, however, before many Jewish authors decided on the vernacular option, that is, to write in Yiddish, the mother tongue of virtually all of Ukraine's Ashkenazic Jewry. While Yiddish was increasingly used in literary works during the first half of the twentieth century, Ukraine's Jewish writers nevertheless continued to use Hebrew, Russian, Polish, German, and in some cases Ukrainian as a means of expression.

The choice of language depended on a number of circumstances, such as geography, family milieu, educational background, personal preference, and specific historical context. Most Jews of Ukraine opted for the language of the state or the empire. Hence, Zeev Jabotinsky and Isaac Babel of Odessa, Ilya Ehrenburg of Kyiv, and Vassilii Grossman of Berdychiv, all residents of deeply russified towns and cities, chose Russian as a means of expression. On the other hand, natives of Habsburg Austrian towns and cities — Karl Emil Franzos of Chortkiv in Galicia, and Rosa Ausländer and Paul Celan of Chernivtsi in Bukovina — preferred German, while Bruno Schulz of Drohobych and Stanisław Jerzy Lec of Lviv, who lived and worked in their native towns when Galicia was under Poland, wrote in Polish. Among the best known of these writers — largely because several of his works have been translated into English — is Joseph Roth, the German-language writer from the far eastern Galician border town of Brody. His several novels and short stories depicted not only the dilemma of traditional shtetl-based Galician Jews caught between the violence of World War I and the challenges of adaptation to the political changes of the interwar years, but also the longing that Jews continued to have for the lost world of Austro-Hungarian peace and social order.

Ukrainian literary production

The emergence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century of literature in the Ukrainian language was in large part the result of the interface between pan-European aesthetic trends and Ukrainian ethno-cultural and national-democratic strivings. Owing to the various stages of colonization, re-colonization, and decolonization that Ukraine went through in modern times, Ukrainian literature often transcended the purely literary boundaries of belles-lettres and instead took on the role of a national revivalist and social-liberation manifesto. At the same time, Ukrainian literature developed in close relation to European literature, using its multiple narrative patterns and genres to convey specifically Ukrainian messages. Often scorned and marginalized as creators of third-rate, peasant-based, backward, and provincial literary works, Ukrainian authors continually sought to prove that they were part of the European literary discourse, that is, that they were a legitimate relative in the family of great European literary traditions and not an abandoned orphan. It is, therefore, not surprising that Ukrainian literati creatively borrowed patterns that opened the European legacy to Ukraine and, in turn, Ukrainian readers to the European literary legacy.

In the ninth century, the Byzantine missionaries Constantine/Cyril and Methodius produced the earliest literary texts that were later used in Ukrainian lands to assist in the conversion of various East Slavic tribes to Christianity. Toward that end, they translated from medieval Greek into Old Bulgarian certain parts of the Gospels that were used in the Christian liturgy between Easter (April or May) and the medieval religious New Year (September) as well for weekly Sunday services. These early texts, now lost to us, are considered the beginnings of Old Slavonic literature in Ukrainian lands and, therefore, the advent of Ukrainian literature. Because those texts were intended predominantly for church services, the language was subsequently called Church Slavonic.

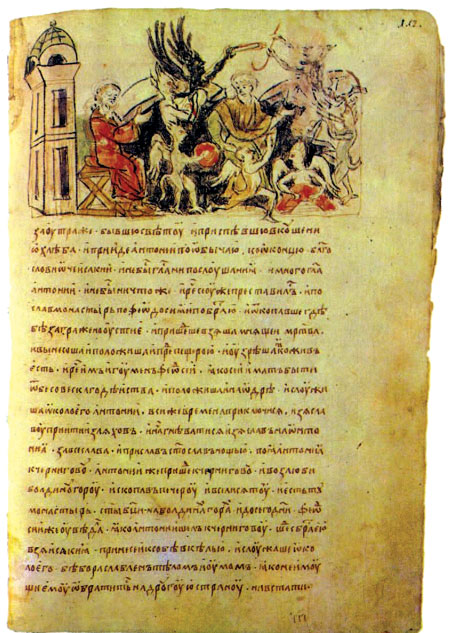

Later translators expanded this core body of texts to include the entire books of the Gospels and other parts of the New Testament. Some of these survived in the form of the eleventh-century Ostromir, the twelfth-century Mstislav and Halych, and the fourteenth-century Reims Gospels. These Church Slavonic translations fostered other kinds of literary development, first and foremost didactic literature, such as the Sermon on Law and Grace (ca. 1050) by Metropolitan Ilarion of Kyiv. The purpose of these was to instill Christian piety, to celebrate the quest for spiritual truth (as opposed to the corrupt mores of the secular rulers of Kievan Rus'), and to promote devotional monastic life in the form of hagiographies (lives of saints). Many of these works were subsequently gathered together in an anthology compiled in the thirteenth century and known as the Kievo-Pecherskii paterik (Patericon of the Kyivan Caves Monastery).

Medieval Ukrainian literature actively absorbed Byzantine Greek cultural patterns. This meant that, from the tenth through fourteenth centuries, dozens of translations of earlier Aramaic, Hebrew, Syriac, and medieval Greek versions of biblical and post-biblical texts (Apocalypse of Abraham, 2nd Enoch, 3rd Baruch, Jacob's Ladder, and others) appeared in Church Slavonic translations. These texts evinced powerful mystical and apocalyptical motifs, and since the earlier versions in other languages have in many cases not survived, the Church Slavonic versions can help us not only to understand the early stages of Ukrainian literature but also to answer questions surrounding the earliest Judeo-Christian mystical traditions.

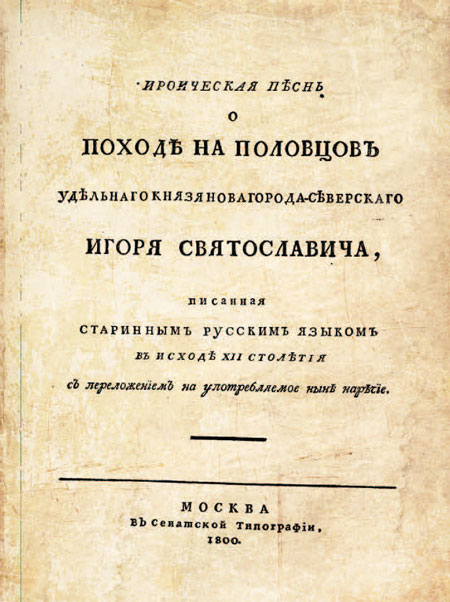

(The Lay of Igor’s Campaign, Moscow, 1800).

Monks at the Monastery of the Caves in Kyiv also created historical narratives in an attempt to justify the new Rus' Eastern Christian polity and inscribe it into the holy history of Christianity. The monk Nestor ("the Chronicler") brought together several earlier chronicles to create a single narrative known as the Povest vremennykh let (The Tale of Bygone Years, or Primary Chronicle, ca. 1100). The tale began by describing the consequences of the biblical flood, along with other key moments of ancient Jewish history, and it explained how with the advent of Jesus the role of the chosen people passed from the Israelites/Jews to the Christians. Most of the chronicle dealt with the "invitation" of the Varangians to what became known as the land of Rus', the story of the "Apostles to the Slavs" Saints Constantine/Cyril and Methodius, the late-tenth-century Christianization of Rus', and the rule of the polity's often warring princes.

The original manuscripts of the Primary Chronicle did not survive, so that what we have is a later more extensive and reworked text. The so-called Hypatian Codex (fifteenth century) created a kind of mega-story (grand historical narrative), which subsequently lent itself to the idea of political continuity between Kievan Rus' and the thirteenth-century principality of Galicia-Volhynia, later viewed by some as a proto-Ukrainian state. Another version of the Primary Chronicle, known as the Laurentian Codex (fourteenth century), aimed to prove that the great city-state of Novgorod in the Russian north, and not the principality of Galicia-Volhynia in the Ukrainian southwest, continued the traditions of Kievan Rus'. Thus, the ongoing heated dispute over who "owns" the past of Kievan Rus', whether modern-day Ukraine or modern-day Russia, was inspired by a literary chronicle from the late-medieval period that is at least five hundred years old.

Perhaps the most influential literary text created in the times of Kievan Rus' was the Slovo o polku Igoreve (Lay of Igor's Campaign) from the late twelfth or early thirteenth century. This anonymous epic poem tells the story of the 1185 raid of Prince Igor, ruler of one of the southern Rus' principalities, against a nomadic steppe people called the Polovtsians. The anonymous author transformed Igor's defeat into a call to unite the scattered Rus' principalities into a single polity, which would help them to withstand future threats from the east. Reading the Lay of Igor's Campaign allows one to reconstruct the complex gamut of medieval Rus' social, religious, and family contexts, which include relations between the prince and his troops, between the Christian Rus' and pagan nomads, between the people and the forces of nature, and between Prince Igor and his beloved wife waiting at home. The Igor story has inspired dozens of later literary versions, including the Ukrainian national bard Taras Shevchenko's "Lament of Yaroslavna" ("Plach Yaroslavny," 1860); several English translations, including one by the renowned Russian émigré author Vladimir Nabokov; and a romantic opera by the Russian composer Aleksander Borodin, Prince Igor (1890). Even the Jewish activist from Ukraine Zeev Jabotinsky was inspired to use The Lay of the Host as the title of his memoir (1928) about the heroic Jewish Legion that fought within the British Army during World War I.

Early-modern authors in Ukrainian lands under Poland-Lithuania wrote their works not only in the official languages of the commonwealth, Polish and Latin, but also in a language called Ruthenian (ruskyi, also referred to as Middle Ukrainian). For example, Metropolitan Ipatii (Adam) Potii composed in Ruthenian and Polish a polemical work called the Antyryzys (1599–1600), a kind of apologia for the newly established Uniate (later Greek Catholic) Church of which he was the first head. About the same time, an anonymous Galician clerical author wrote a complex historical chronicle, Perestroha (Exhortation, ca. 1600), in which he retold tales from many earlier chronicles and sympathetically portrayed sixteenth-century political and religious events such as the emergence of the Uniate Church.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Orthodox members of the Polish nobility feared that Roman Catholicism (and its Uniate allies) would suppress what they considered genuinely Eastern-rite traditions. To prevent this from happening, they established nearly a thousand schools and seminaries, of which the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was the most renowned. Out of this scholastic tradition came new literary genres and trends epitomized by the writings of the polylingual Teofan Prokopovych. When, in 1716, the tsar of Muscovy Peter I invited Prokopovych to St Petersburg to oversee the reform of the Russsian Orthodox Church and its newly created council of bishops (synod), the prelate from Kyiv felt he needed to justify himself in the eyes of the Muscovite church hierarchs who considered him a parvenu. To this end, Prokopovych conceptualized the tripartite brotherly unity of the Slavic peoples (Ukrainians, Belarusans, Russians), invented the concept of the Russian Empire (to replace Muscovy), and advanced the idea of Russia as the only legitimate heir to Kievan Rus'. Hence, the key Russian imperial concepts were actually advanced by a Ukrainian educator and thinker!

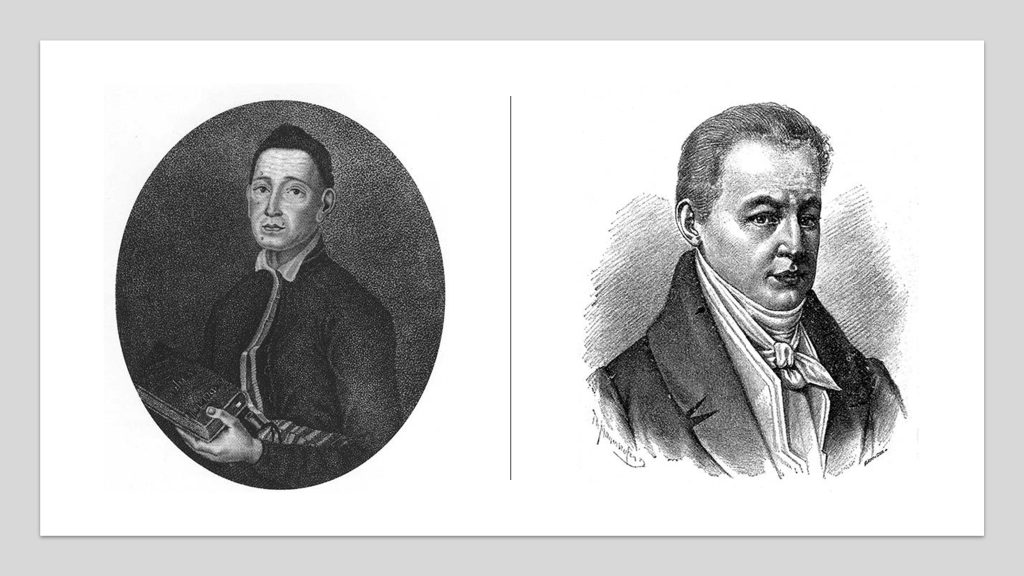

Also trained at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and at several central European universities was the philosopher and poet Hryhorii Skovoroda. In stark contrast to Prokopovych, Skovoroda shunned lucrative positions whether in the church or in secular society. Instead, he moved from place to place with his flute and manuscripts, teaching in eastern and central Ukraine and writing philosophical treatises, parables, and prose in a fusion language of Middle Ukrainian and Church Slavonic intermixed with elements from Latin and Russian. He also composed music and wrote songs that were collected in his Sad bozhestvennykh pisnei (Garden of Divine Songs, ca. 1757). Skovoroda's highly innovative compositions advanced what one might call a "philosophy of life" that included elements of Renaissance neo-Platonism and seventeenth-century mysticism. His thought was based on the centrality of human self-knowledge, which he viewed as the key manifestation of spiritual freedom, and was expounded in works such as "Narcissus, or a Conversation about Knowing Thyself"; "Conversation of Five Co-travelers about Genuine Happiness in Life"; and "A Talk about How Easy It Is to Be Gracious." Owing to highly problematic relations between Skovoroda and the official Orthodox Church in what was then the Russian Empire, almost none of his works were published during his lifetime. Hundreds were circulated in manuscript, however, and after Skovoroda's death some appeared in published form. Drawing on dozens of contemporary philosophers and religious thinkers, Skovoroda's writings had an enormous influence on the subsequent development of Ukrainian literature, in particular on its leading nineteenth-century representatives, Ivan Kotlyarevskyi and Taras Shevchenko. Modern Ukrainian literature can be said to begin with Ivan Kotlyarevskyi, who wrote the heroic-comic epic poem Eneyida (Aeneid, 1798). In this work, Kotlyarevskyi presented the epic post-Trojan War events described by the Roman poet Virgil, in which Ukrainian Cossacks became the protagonists rather than the ancient Trojans and Romans. Relying heavily on the tradition of French heroic-comic poems, Kotlyarevskyi wrote his parody in a colloquial Ukrainian language peppered with peasant idioms, Cossack verbiage, and the profane speech of contemporary seminary students. Not only did he satirize the various strata of the Russian imperial society to which he belonged, he also lifted Ukrainian to the level of Virgil's Latin epic poem and, in a mocking, tongue-in-cheek manner, presented Ukrainians as an ancient people. This manner of delivering politically provocative messages in mocking form came to be associated in Ukrainian literature with his name (kotlyarevshchyna).

Romanticism presented new opportunities for Ukrainian writers. The Romantic poets of Germany preached that the Volk, ordinary rural people, embodied the absolute truth, that their folklore (tales, epic narratives, songs) represented the highest literary value, and that the poet's mission was to reveal the Volksseele, the soul of the people, by using folklore as a conduit. Under the impact of these ideas, three Galician writers — Markiyan Shashkevych, Yakiv Holovatskyi, and Ivan Vahylevych — turned to collecting Ukrainian folklore in Austrian Galicia. In their collection Rusalka dnistrovaya (The Nymph of the Dniester, 1837), they included folkloric texts, translations from European literature, and philological studies. The fact that they used the Ukrainian vernacular and a simplified form of the Cyrillic alphabet for the first time in Austrian Galicia frightened the Habsburg authorities, who, at a time of conservative reaction to revolutionary ideas, saw any kind of change and innovation as a threat to the established social order. Most important, it was the Galician Ukrainian writers' discovery of the beauty of Ukrainian folklore that made their collection an epoch-making event.

On the other side of the border in the Russian Empire, Taras Shevchenko placed Ukrainian literature firmly on the European literary map as nobody before or after him was able to do. A peasant-serf who eventually became an outstanding painter, Shevchenko arrived in the imperial capital of St Petersburg to discover European and Russian Romanticism and imbue it with new meaning. In his Kobzar (The Minstrel, 1840), Haidamaky (The Haidamaks, 1841), and Try lita (Three Summers, 1845), Shevchenko employed Romantic patterns to reveal what he defined as the rebellious and freedom-loving soul of the Ukrainian people, to celebrate its violent yet justified resistance to social oppression, to mock the ruling elites (whether Russian, Ukrainian, or Polish), and to bemoan the fate of Ukrainians, a widowed and orphaned people suppressed for centuries both socially and culturally. Shevchenko emerged as a poet-messiah who, like Byron fighting for the Greeks or Mickiewicz advocating for the Poles, came to redeem his people through poetry, using the rhythms and meters of Ukrainian folklore to convey the subversive, anti-imperial message of Ukrainian revival and liberation. Shevchenko's life experience — he was persecuted, exiled, and for a decade confined to army barracks — allowed him to take on the image of a national bard, a Christ-like martyr sacrificed for the sake of his own people.

Shevchenko's friend Panteleimon Kulish, who wrote, like Shevchenko, in Ukrainian and in Russian, realized that his message would be much stronger if evidence could be marshaled to prove the distinct ethnic and cultural character of the Little Russians (as ethnic Ukrainians were known at the time), who had no choice but to live under Moscovite and Russian rule. An ambitious though contradictory public figure, Kulish published newspapers, journals, and almanacs to convey his message. He also wrote historical studies and novels glorifying — and thus creating in literary discourse — the notion of the troublesome Ukrainian past. Most important, he published several studies on Ukrainian ethnography and folklore, and co-authored the first Ukrainian translation of the Bible.

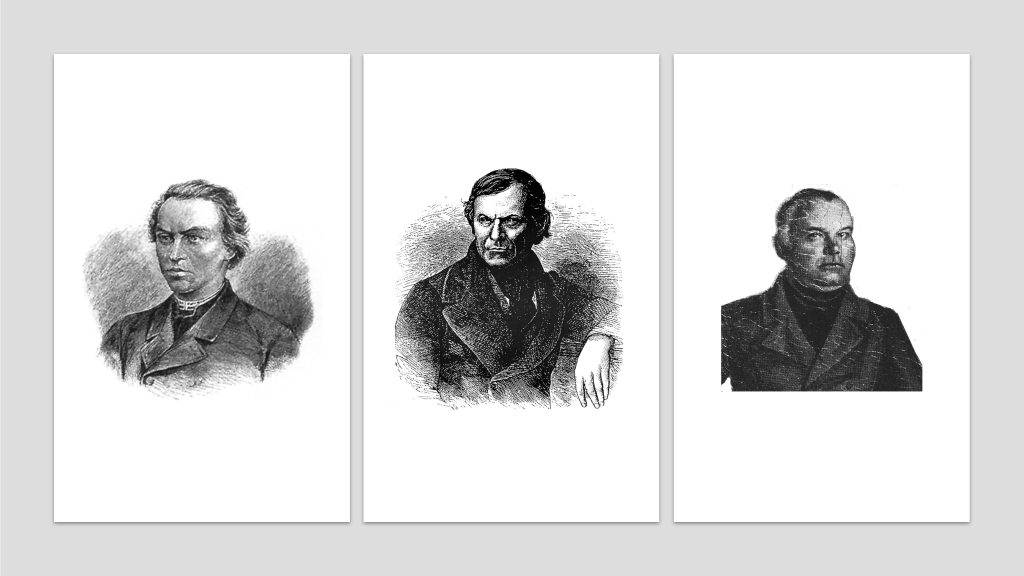

In the second half of the nineteenth century, two trends informed Ukrainian literary endeavors: political populism and literary naturalism. Writers like Ivan Nechui-Levytskyi, Marko Vovchok (pseudonym of Mariya Vilinska), and Panas Myrnyi crafted realistic images of contemporary ethnic Ukrainians: former serfs liberated but with insufficient land, who then became impoverished and often had to move to large urban areas, where they were forced into the role of poorly paid blue-collar hired workers, seamstresses, and prostitutes. These writers adhered to the aesthetic principles of Émile Zola, with his emphasis on the social milieu as the major force shaping an individual's character. Although focused on the enslaving impact of their social milieu at a time of urbanization and industrialization, they also captured the unique process of ripening national self-awareness embodied by their protagonists in late imperial Russia.

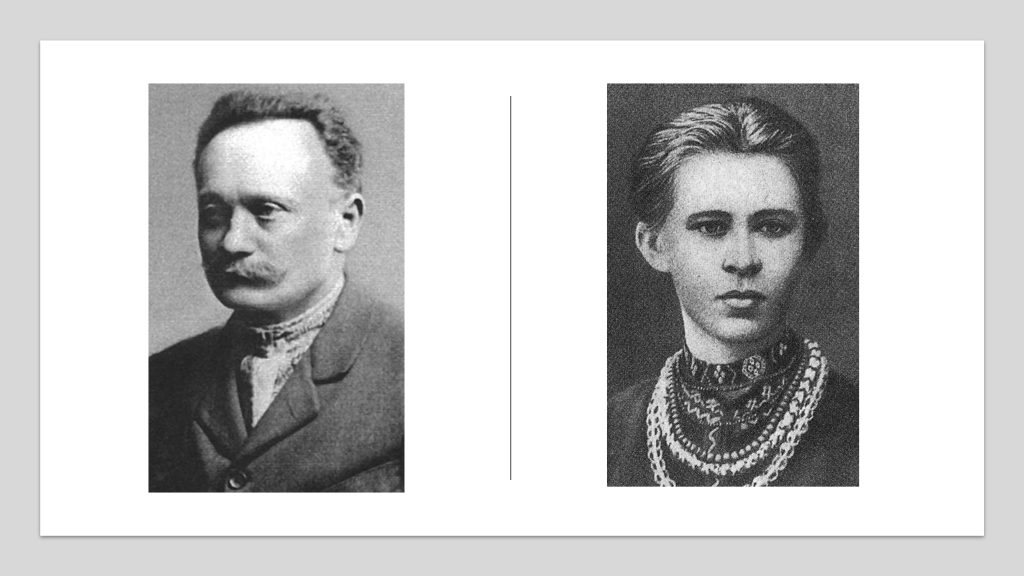

In Ukrainian lands within the Austrian Empire, the dominant literary figure was Ivan Franko. He moved from populist-realism to a social-democratic vision of the Ukrainian future with pronounced nationalist underpinnings. The phenomenally prolific Franko worked in virtually every genre — journalism, literary criticism, translation, philology, and the study of history and folklore — although it was as a novelist and a poet that he acquired national renown. His novels, such as Boryslav smiyetsya (Boryslav Is Laughing, 1881), stylistically combine French naturalism with elements of Marxist class analysis in their depiction of the rising oil industry in East Galicia, the pauperization of the Ukrainian masses, and the emerging class struggle among the new Ukrainian proletariat. In his poetry, however, Franko reveals himself as more a revolutionary romantic than a social realist. His poetic verses courageously called for the Ukrainian people to demolish what he saw as the overwhelming burden of social oppression, regardless which power, imperial Austria or Russia, was the cause.

Meanwhile, in the Russian Empire Lesya Ukrayinka was also caught up in revolutionary romantic fervor. A poetess of unsurpassed lyricism and masterful artistic sensitivity, she drew heavily from her prodigious knowledge of European literature, particularly Greek mythology and European modernist drama. She created plays in which her non-conformist and highly idealistic male and female characters defied the corrupt reality of contemporary society, challenged social conformism, and, if necessary (like Mavka in "The Forest Song," 1912), paid with their lives for their courageous and lonely choices.

But what was the price of such defiance and how could it be translated into action within real social circumstances? The answer is found in the writings of perhaps the most important Ukrainian playwright of the early twentieth century, Volodymyr Vynnychenko. He placed uneasy ethical dilemmas before his characters not in some folkloric or historically distant past, but in most unusual contemporary situations: the criminal underworld, a prison cell, a Ukrainian village caught in revolutionary upheaval, and encounters among revolutionaries of differing political orientation. Yet how could one's ethical integrity be preserved when circumstances required immediate action? The negotiation of values was far from being just a literary question for Vynnychenko. As one of the three top leaders of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic, he tried to work in the political world but failed. Thereafter, he settled as an émigré writer in France. While he spoke out against the Soviet regime, he disappeared from the Ukrainian literary horizon for more than half a century.

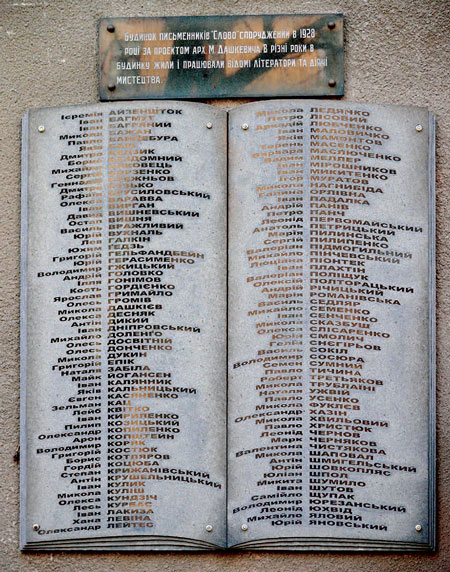

The period of Ukrainianization and national communism that characterized Soviet Ukraine during the 1920s created exceptional opportunities that resulted in a period of literary renaissance. Among the leading writers during the renaissance was Mykola Khvylovyi (pseudonym of Nikolai Fitilev). He exemplified the very essence of utopian national communism, which he saw as offering an opportunity to abandon old Ukrainian folklore-based patterns and open Ukrainian literature wide to European modernistic influences. Mykhailo Semenko and Mykola Bazhan framed their poetry in the form of a productive conversation with Russian and European futurism, while Ivan Kulyk, sympathetic to the proletarian masses, introduced the rhythms of Afro-American musical folklore into Ukrainian poetry. No less proletarian-minded was Yurii Smolych, who, following British examples, employed the narrative techniques of science fiction. At the same time, Maksym Rylskyi, Mykola Zerov, and Yurii Klen (pseudonym of Oswald Burghardt) explored the legacy of French symbolism and transformed it into their own style of Ukrainian Neo-Classicism, while Valerian Polishchuk experimented with Austrian modernistic story-telling techniques. The literary renaissance connected with the period of Ukrainianization was a particularly fascinating time when writers of different ethnic origins — Russian, German, or Jewish — made a home for themselves in Ukrainian cultural circles.

When, in the 1930s, the Soviet regime under the increasingly powerful Stalin decided that socialism could be built in one state and that leftist internationalist ideas were superfluous, these wonderful literary developments came to a halt. Dozens of Ukrainian literati were arrested, accused on the bogus pretext of being enemies of the people and subversive nationalists, sentenced to long terms in prison, and in some cases executed. Most of those who avoided arrest, poets such as Maksym Rylskyi and Pavlo Tychyna, were intimidated to such a degree that they never again lived up to their own previous achievements. The subsequent generation of writers, such as Mykhailo Stelmakh, Natan Rybak, Oleksandr Korniichuk, and Oles Honchar, who came into their own in the 1940s and 1950s, worked within the parameters of the only endorsed stylistic trend: socialist realism. They, like all writers, were obliged to glorify the class struggle of the pre-revolutionary proletariat and create positive examples for present-day socialist workers who should feel optimism for a bright Communist future. Their stylistically quite sophisticated, yet artistically non-engaging, works avoided any dialogue with contemporaneous European literary trends.

It is, therefore, no surprise that the most important and innovative Ukrainian literary texts of the 1940s and 1950s appeared not in Soviet Ukraine but in the diaspora. Writers such as Ihor Kostetskyi (pen-name of Ihor Merzlyakov), Ulas Samchuk, Yurii Kosach, and Ivan Bahryanyi (pseudonym of Ivan Lazovyagin) chose as their subject matter the reconstruction of the recent past of which they were witnesses and victims. Drawing on elements of European (German and French) existentialism, Samchuk created the epic novel Mariya (1934) about the Great Famine/Holodomor in Ukraine; Bahryanyi explored in novels the Great Terror of the 1930s; and Yurii Kosach looked to the distant past in a series of stylistically innovative historical novels on the seventeenth-century Cossack revolts. Kostetskyi, perhaps the most talented among these diaspora literary figures, established himself as the founding father of the Ukrainian absurdist style, which preceded and foreshadowed the writings of Samuel Beckett.

During the short period of the so-called political Thaw in the Soviet Union, the generation of the 1960s boldly challenged established ideological restrictions and revived the artistic experiments of the 1920s with an emphasis on Ukrainian symbolism, the historical past, and folklore. Hryhir Tyutyunnyk drew upon the tradition of Ukrainian Baroque in his rural short stories, while Yurii Shcherbak in his urban novels explored ethical aspects of existentialist literature. The most important breakthroughs, however, came in the poetry of Vasyl Symonenko, Lina Kostenko, Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, Leonid Kiselev, and Moisei Fishbein, among others. Breaking with the canons of socialist realism, these poets placed the suffering thinker concerned about his land and culture at the epicenter of their imaginary realm, thereby openly rejecting what they considered the colonialist conditions of their contemporary Ukrainian homeland. Ivan Dzyuba, the prolific literary critic and philologist of philo-Semitic convictions, was among the key thinkers of this informal 1960s group.

Once the period of the Thaw ended with arrests and other forms of government repression, some of the representatives of the 1960s generation, such as the poet Dmytro Pavlychko, adapted to the new political situation. Others refused to capitulate, the most profound and rebellious among them being Vasyl Stus (nominated in 1985 for the Nobel prize). Aside from his literary work, Stus was active in the dissident movement and publicly protested the Soviet government's persecution of the nationalist-minded Ukrainian intelligentsia. Unsurprisingly, these poets (with the exceptions of Symonenko, beaten to death by the security organs in 1963, and Stus, who died in prison in 1985) were at the forefront of the new political strivings on the eve of and immediately after the declaration of Ukraine's independence in 1991.

In independent Ukraine, censorship was lifted and the now antiquated socialist-realist writers lost their readership. Moreover, the state no longer promoted their works. Instead, the works of dozens of writers from the 1920s and 1930s who had been exiled or executed were returned to readers through extensive posthumous publications. Numerous diaspora writers and poets also made their way for the first time to readers in Ukraine, and even into the curricula of secondary schools and colleges. Although in recent years book-market sales have dropped precipitously (Ukraine's population ranks among the lowest in Europe in terms of reading), new Ukrainian writers can nonetheless incorporate western European literary trends into their works. The result has been a new generation of writers who can be classified as post-modernists (Yurii Andrukhovych, Serhii Zhadan, Oleksandr Irvanets); feminists (Oksana Zabuzhko); national chroniclers (Mariya Matios, Valerii Shevchuk, Yurii Vynnychuk); satirists and humorists using the fusion language surzhyk (Bohdan Zholdak, Mykhailo Brynykh); and fantasists, often writing in Russian (Andrii Kurkov). Also, by the outset of the twenty-first century, the previous barrier between the diaspora and the literary world in Ukraine has disappeared. For example, the poet Vasyl Makhno freely travels between Chortkiv in Galicia and New York in the United States, allowing him to create urban verse that explores different cultures, countries, urban profiles, and human types.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.