Chapter 7.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 7.2

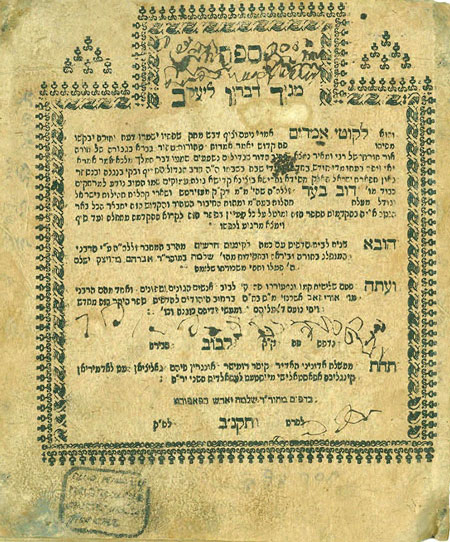

Jewish literary production

Before the era of liberalism and the secularization that characterized the second half of the long nineteenth century, the most widespread genres of literary creativity in traditional Jewish communities of Ukraine were books for individual and group study, liturgy, and religious education. These included rabbinic responsa, commentaries on the classical Judaic texts, legal codices, ethical treatises, theological compositions, tractates on Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism, and, of course, prayer books. They were predominantly written in Hebrew, the major mode of written communication among Jews. The earliest such works by authors in Ukrainian lands date from the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

Some of these books became so influential that Jews used their titles as the equivalent of the names of the authors, while the authors themselves were referred to by the names of their books. For example, Joel Syrkes, who served in the early seventeenth century as a rabbi in Medzhybizh, published what became a famous collection of responsa titled Bayt hadash (New House). In this work Syrkes proposed many adjustments to religious law, including permission to read secular books on the Sabbath, allowing women to wear men's clothing in severe weather conditions, and the idea that Jewish doctors would not be violating the sanctity of the Sabbath if they needed to attend to their Christian clients. Later generations referred to Syrkes as B" H (pronounced bakh) after the abbreviated name of his book; thus, the Bakh wrote, the Bakh said, the Bakh maintained, etc. This manner of referring to an author by emphasizing his work and de-emphasizing his person was quite common in traditional Jewish culture.

Among the most famous of rabbinic responsa was the Noda bi-Yehudah (Known in Juda) by Yehezkel Landau, an influential eighteenth-century rabbinic scholar who studied in Brody and eventually moved to Prague. Landau endorsed the study of secular subjects, argued for allowing autopsies in certain cases (otherwise forbidden in Judaism), introduced regulations to protect women in divorce cases, and vehemently fought against sectarian trends in Judaism, in particular the Sabbatean and Frankist movements (see chapter 2). In the nineteenth century, the most significant responsa was the six-volume Shoel u-meshiv (Answer and Reply) by Joseph Nathanson, the chief rabbi of Lviv. Its decisions endorsed a new technology for making Passover matzo and allowed the use of foods and clothing mechanically produced at newly established factories owned by Gentiles, which the rabbi himself went to oversee.

Ukraine was the birthplace of a number of mystical texts of primary importance. Among these were the early-sixteenth-century Shoshan sodot (The Rose of Secrets), a commentary by Moshe of Kyiv on the medieval Sefer yetsirah (Book of Creation); the mid-seventeenth-century Sefer karnayim (Book of Beams), by a prominent Kabbalist from Volhynia, Shimshon of Ostropolye; and the enormously popular Kabbalistic prayer book Shaarei Tsion (Gates of Zion, ca. 1650s), composed by the famous chronicler Natan Hannover. It was in the early eighteenth century that the most important books on Kabbalah were published for the first time at the Zhovkva (Polish: Żółkiew) printing press in Galicia.

The rise of Hasidism brought about a wide variety of new books and genres, particularly since Hasidic masters were striving to undermine the criticism of their opponents (mitnagdim); they aimed to show that Hasidism significantly enriched Judaism, that it enhanced Judaic values, and that the Hasidim were not sectarians. Among the best-known works that resulted from these polemics were commentaries on the oral and written Torah, such as the Toldot Yakov Yosef (History of Yakov Yosef, 1780), the Magid devarav le-Yaakov (A Preacher's Words to Jacob, 1781), and the Kedushat Levy (Sanctity of Levy, 1798). These books introduced the esoteric and secret meaning of Judaic books and rituals; they showed how personal piety might produce miracles and how Kabbalistic meanings made complex aspects of Judaic ritual transparent and understandable; and they were instrumental in bringing new followers to the Hasidic masters (tsadikim), now seen as the pillars of Jewish traditional life. About the same time, new genres of Hasidic writings appeared, including sipurey maysiyos (stories of wondrous deeds), popular tales, and at times rather sophisticated allegories usually in Yiddish, either about or by wonder-working Hasidic tsadikim. These works, many of which were published by the newly established printing presses in Ukraine's shtetls, had a significant impact at the time not only on the Hasidic masses but also later on twentieth-century Jewish thinkers of whom Martin Buber, Solomon Schechter, and Abraham Joshua Heschel were the most prominent.

The enlightened maskilim of eastern Europe who did not like the Hasidic masters sought to disrupt their impact by disseminating ideas of the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah. They called for innovative secularized education and were particularly critical of the Hasidic masters. For example, Heshbon ha-nefesh (Moral Accounting, 1808), a treatise by an author from the small border town of Sataniv in Russian-ruled Podolia, Mendel Lefin, took the view that reliance on a Hasidic master was a corrupt practice and simply reflected the gullibility of the Jewish masses, a shortcoming that he proposed to overcome through individual self-perfection. Another enlightened educator, Joseph Perl from Ternopil in Austrian-ruled Galicia, went even further in a work, Megaleh temirin (Revealer of Secrets, 1819), which is considered the first Hebrew-language novel. In this satirical composition, Perl "collected" fake correspondence between Hasidic followers obsessed with finding and destroying an anti-Hasidic composition. Other challenges to Hasidism came from the pen of Yitshak Ber Levinzon, one of the most important enlighteners active in Ukrainian lands under the Russian Empire. His Teudah be-Yisrael (Testimony for the Jews, 1827), which insisted on the necessity of a secular approach to teaching Hebrew, was followed by an anti-Hasidic satire, Divrei tsadikim (Words of the Righteous, 1830).

Two unparalleled compositions by Jewish enlighteners (written in the 1820s–1830s but published much later) paved the way for a new way of thinking. One was the Hebrew treatise More nevukhei ha-zman (A Guide for the Perplexed of Our Time, 1851) by Nahman Krochmal from the Austria's Galician border town of Brody, who used key concepts of German philosophy (Herder and Hegel) in order to prove that the Jews were a nation, not a religious tribe, and that they possessed a unique Volksgeist (national spirit). In other words, they belonged to that group of historical peoples who had a future. Such a reassessment triggered a Jewish national revival which, in turn, had a major impact on Heinrich Graetz, the founding father of Jewish historiography, and on Theodor Herzl, the founding father of the Zionist movement.

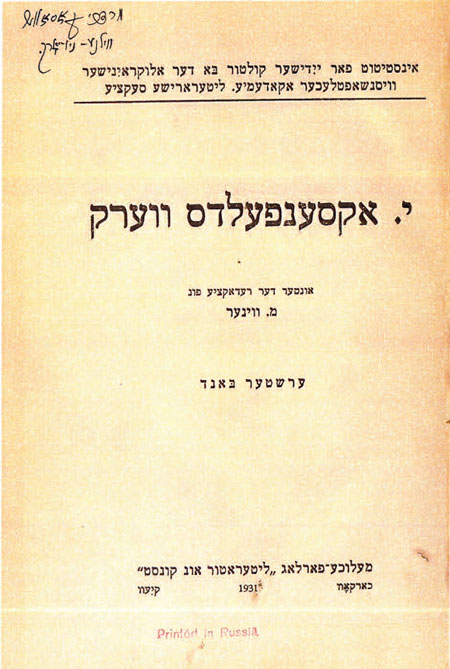

The second of Ukraine's influential Jewish enlighteners and a harbinger of a major literary change was Yisroel Aksenfeld from Nemyriv. In works such as the novel Dos Shterntikhl (The Headband, 1861) and the play Der ershter yiddisher rekrut (The First Jewish Conscript, 1862), Aksenfeld drew a poignant portrayal of the traditional nineteenth-century Jewish shtetl, permeated with scintillating humor and characterized by precise ethnographic detail expressed in rich Yiddish language. Aksenfeld's stylistic and linguistic innovations preceded the more famous Mendele Moykher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem by more than a quarter of a century.

The Reform Era launched in the Russian Empire by Tsar Alexander II in the 1860s and at the same time the emancipation of the Jews in the Habsburg Empire under Emperor Franz Joseph created socio-cultural conditions that encouraged literary genres best expressed in the newly emerging Jewish press. The appearance of Russian-, Yiddish-, Hebrew-, Polish-, and German-language newspapers provided dozens of new avenues for enlightenment-minded individuals who sought to reform contemporary society, whether Russian and Austro-Hungarian societies as a whole or their specific Jewish component. Since the Jewish reading public in both empires was primarily Yiddish-speaking, authors who turned to Hebrew (Mendele Moykher Sforim) or to Russian (Sholem Aleichem) were soon forced to face reality. If they wanted to have an impact on their readers, they would have to use Yiddish. This was a time, the mid-nineteenth century, when Jewish secular literary culture (journalism and belle-lettres) was expressed in all eastern European languages as well as in Hebrew and Yiddish.

The choice of language signified newly manifested cultural loyalties and represented the literary culture in which a writer would invest his or her talent. Because of the various linguistic choices, several Jewish literatures emerged in Ukrainian lands of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires during the second half of the nineteenth century. Hundreds of publications in different languages and in practically every genre of literary creativity appeared.

Some writers introduced Jewish motifs when writing in languages other than Hebrew and Yiddish, while others immersed themselves entirely in the larger Russian, Polish, German, or Ukrainian literary tradition. Still others created what could be considered works of Jewish literature written in the non-Jewish languages of central and eastern Europe. For example, those who sought integration into the imperial Russian milieu, like the Odessa writer and publisher of the newspaper Razsvet (Dawn) Osip Rabinovich, chose Russian as his medium. His example was followed by dozens of writers, among whom the most notable were Isaac Babel and Zeev Jabotinsky from Odessa, Ilya Ehrenburg from Kyiv, Vasilii Grossman from Berdychiv, Boris Yampolsky from Bila Tserkva, and the entire Odessa school of Russian-Jewish satirists ranging from Ilya Ilf to Mikhail Zhvanetskii.

The multilingual reality of nineteenth-century Ukrainian lands raises several questions. How should the writers who chose to express themselves in Polish, Russian, and German be classified? And how does one measure the meaningful presence of Jewish themes in their works? While critics have conflicting views on this issue, there is a consensus that literature in Yiddish and Hebrew, the languages used most often if not exclusively by Jews, should be considered Jewish literature.

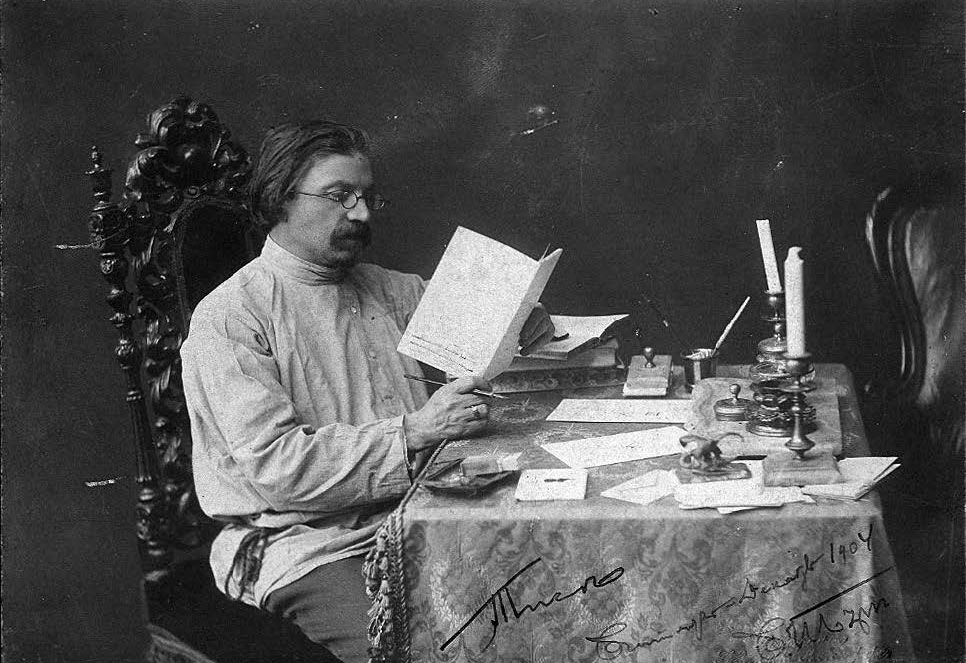

The period known as the fin de siècle (the three or four decades before the outbreak of World War I in 1914) witnessed a blossoming of Yiddish-language and the beginnings of Hebrew-language literature. The towering figure during these decades was Sholem Aleichem (b. Shalom Rabinovitz), who used popular spoken Yiddish filled with idioms and colloquialisms to create tragicomic images of the quintessntial (though imaginary) shtetl that he called Kasrilevke. In his many prose works, Sholem Aleichem also crafted the prototype of a self-reflecting, entrepreneurial, comical, and poignantly unlucky Jew trying to make both ends meet and provide for his family. He not only portrayed the encounter of the vulnerable "little Jew" with the outside world — ranging from London to Odessa and marked by an environment of antisemitism, assimilation, revolutionary politics, radicalism, and violence — he also celebrated the warm humor and Jewish wisdom with which his characters reacted to that outside world. This combination of humor and wisdom also characterized the works of two writers, both connected to Bukovina: the Yiddish poetical fables of Eliezer Shteynbarg (Durkh di briln/Through Eyeglasses, 1928) and the grotesque fantasy of Itsik Manger (Di vunderlekhe lebns-bashraybung fun Shmuel-Abe Abervo/The Wonderful Autobiography of Shmuel-Abe Abervo, 1929).While Yiddish-language Jewish writers grappled with the relations between the traditional shtetl and the rise of ever larger cities, Hebrew-language writers boldly placed their characters at the threshold of modern urbanized life. Hayim Nahman Bialik from Zhytomyr and Shaul Tshernichowsky from a village in the southern Ukrainian steppe region both sought to recreate in their Hebrew-language poetry Slavic and European literary legacies ranging from neo-Romantic imagery to a syllabic tonic metrical system. Influenced by the rise of Zionism, they pondered the uneasy relation between the old European Jewish centers and the rejuvenated realm of Jewish immigrants to the land of Israel. In addition, Tchernichowsky penned unparalleled Hebrew translations of Finnish (Kalevala), Old Rus' (The Lay of Igor's Campaign), and American (Hiawatha) literature, thereby actively absorbing their imagery and meter into the growing secular Hebrew literature.

Other Hebrew writers in Ukrainian lands, such as Mikhah Yosef Berdyczewski from Medzhybizh and Yosef Hayim Brenner from Novi Mlyny near Chernihiv, were particularly sensitive to European influences. Under the impact of the fin-de-siècle fixation on human disease, the criminal underground, and the instability of the individual psyche and libido, Berdyczewski explored marginal characters and situations among Jews, whereas Brenner investigated the clash, reflected in graphic language, between people's expectations and the brutal reality in World War I Ottoman-ruled Palestine. The Nobel Prize laureate Shemuel Yosef Agnon (b. Czaczkes) from the eastern Galician town of Buchach, who later lived in Germany and Israel, combined an interest in the Galician shtetl with concern about the hopes and fantasies of Jewish settlers in Palestine. In novels such as Oreah natah lalun (A Guest for the Night, 1939) and Edo and Enam (1950), Agnon portrayed the imminent disappearance of eastern European Jewry and soberly assessed the unrealized messianic expectations of Zionism for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

The fate of Hebrew-language literature took a decided turn for the worse in the Soviet Union. This is because the ideologists of the new revolutionary worker's state considered the Hebrew language a medium of the wrong ideology (nationalism), the wrong worldview (religion), and the wrong class (bourgeoisie). On the other hand, they saw Yiddish as a genuine folk language that was appropriately proletarian and atheist. Therefore, in the 1920s, the Soviet authorities created incomparably favorable conditions for the development of Yiddish culture, literature, and the press. Yiddish writers and poets who had left the country during the political and social turmoil following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution now returned and established themselves first in Kharkiv and later in Kyiv.

In both those capital cities of Ukraine, Yiddish-language Jewish poets and writers who were natives of small towns and villages across Soviet Ukraine — Leyb Kvitko from Holoskovo near Odessa, Perets Markish from Polonne, Itsik Fefer from Shpola, Dovid Hofsteyn from Korostyshiv, Dovid Bergelson from Sarny — enjoyed enormous prestige and a mass following. Many, however, were forced to abandon their experimental innovations with style and imagery, and instead work within the artistic guidelines of socialist realism and its overwhelming concern with the class struggle and Communist ideology. In the end, while these writers may have achieved literary success, they often did so at the expense of artistic integrity. For example, Dovid Bergelson had earlier produced several outstanding prose works (such as Nokh alemen / When All Is Said and Done, 1913), which explored the alienation and existential crisis facing the individual. During the Soviet period, by contrast, he adopted the socialist-realist approach, as in the epic novel Bam Dnyepr (On the Dnieper, 1932), in which the main character, a Jewish youth and most likely a future urban proletarian, is portrayed as at odds with his corrupt shtetl environment.

After World War II, the world of Jewish literature changed dramatically. The only remaining significant Hebrew-language poet in the Soviet Union, Hayim Lenski from Soviet Belorussia, died in the gulag. Almost all the other distinguished Jewish writers and poets, such as those active in the Soviet Union's Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, were arrested in 1952, accused of espionage and "rootless cosmopolitanism," tortured, and executed. As the Kyiv-based literary critic Myron Petrovsky put it: Hitler murdered Jewish readers, while Stalin murdered Jewish writers. Nevertheless, by the second half of the twentieth century, the very few survivors of the late-Stalinist era anti-cosmopolitan campaign were able to publish some works in Yiddish. Among them were gulag survivors from Soviet Ukraine, Nosn Zabara from Rohachiv in Volhynia and Gershl Poliakner from Uman, who in novels such as Galgal hakhoyzer (The Revolving Wheel, 1979) and Geven amol a shtetl (There Once Was a Shtetl, 1990) connected the world of Sephardic Jews from Spain with that of Ashkenazic Jews from eastern Europe. By the last decade of the twentieth century, the most prolific Yiddish writer in Ukraine was the Bukovinian Jew Yoysef Burg. He began his literary career before World War II and continued to publish after the war, producing numerous novels, short stories, and sketches, such as Dos lebn geyt vayter (Life Is Going On, 1980).

Jewish-Ukrainian literary cross-fertilization

Regardless of their language of expression, Jewish writers in Ukraine remained loyal to Ukrainian and Jewish themes. The German-language Emil Franzos, for example, was perhaps the first writer to portray Jews and Ukrainians in Galicia and Bukovina. Mendele Moykher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem poked fun at the mutual cultural stereotypes of the Other among Jews and Eastern Orthodox. Mendele, in particular, used long quotes in Ukrainian (transliterated with Hebrew letters) to create a hilarious imaginative Yiddish-Ukrainian linguistic environment for his characters. The Russian-language Vasilii Grossman portrayed the precarious fate of the two Soviet peoples, Ukrainians and Jews, by creating direct parallels between the Holodomor and the Holocaust. One of the most powerful examples of literary multilingualism was Piotr Rawicz, a Lviv-born Jewish writer, who spent two years in Auschwitz as a "Ukrainian" prisoner. In his French-language novel Blood from the Sky (1961), he created an image of a Galician Jew who is trying to escape deportation to the death camps by using forged papers and presenting himself as a Ukrainian intellectual. He manages to escape precisely because of his profound knowledge of the Ukrainian language and literature, which he uses to dupe the Nazis.

Several works of Ukraine's Jewish writers not only proved to be of the highest European caliber, they at the same time enriched Polish, German, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and Ukrainian literatures. Despite their language preference and choice of association with either the imperial or stateless colonial culture, many authors were attached to Ukraine. Thus, the Zionist Zeev Jabotinsky argued repeatedly in his numerous feuilletons against Russian chauvinists while underscoring the greatness and beauty of the distinctly Ukrainian literature and language. The Hebrew writer and Nobel Prize winner S.Y. Agnon consistently returned in his imagination to his native Buchach, which reappears under various names in novels and short stories. Sholem Aleichem immortalized in his Yiddish narratives the inhabitants of Anatevka, filling his prose with dialogues in Ukrainian transcribed in Yiddish. Ultimately, the Russian-language Vasilii Grossman was the first among Soviet writers to equate the Holodomor and the Holocaust and to portray Ukraine's tragedy as a state-orchestrated famine, doing so long before anyone in the Soviet Union even dared think about any similarity between those tragedies in the lives of the two peoples. The loyalty of Jewish writers to Ukrainian themes went far beyond the requirements of couleur locale or of images from a nostalgic childhood and represented instead a high level of solidarity and empathy toward things Ukrainian.

The few multilingual Jews who turned to the Ukrainian language and sought integration within the country's intelligentsia and culture did so precisely at a time, the 1920s, when ethnic Ukrainians were experiencing a national revival. As they were rejecting previous romantic and positivistic aspects of nationalism, they were forced to reassess stereotypes and, in the process, reimagine the Jew.

To be sure, ethnic Ukrainian writers had to grapple with a formidable set of anti-Jewish stereotypes expressed in existing literary works that were inspired by the early-nineteenth-century historic work, Istoriya Rusov, with its powerful xenophobic invectives, as well as ballads carefully edited by romantic-minded poets and presented as genuine folklore. In the most controversial of his works, Haidamaky (The Haidamaks), the national bard Taras Shevchenko went far beyond the romantic stereotypes, showing sympathy to an individual Jew and bemoaning the tragedy of a Ukrainian rebel dragged into a bloody whirl of violence. Later, realistic writers such as Panas Myrnyi may not have been sympathetic to what they called Jewish exploitation; nevertheless, they too portrayed individual Jews, particularly women, as sharing values and culture with rural ethnic Ukrainians. Two of the country's most prolific and widely read authors, Lesya Ukrayinka and Ivan Franko, sought to mobilize the Ukrainian people under anti-imperial mottos, all the while drawing parallels between the historical fate of modern-day Ukrainians and the Jews escaping Egyptian bondage. By the early twentieth century, dozens of Ukrainian writers across the political spectrum, from the left-wing nationalist Volodymyr Vynnychenko to the Soviet anti-nationalist Yurii Smolych, presented Jews in a nuanced, often contradictory, yet humane fashion. For them, Jews like ethnic Ukrainians were victims of history.

This rediscovery of Jews and the affinities between the two peoples were far from merely literary. Ukrainians and Jews also discovered each other through intense literary and personal relations. Late in the nineteenth century, several Jews, mostly from Yiddish-and Russian-speaking families, joined the narrow circles of Ukrainian intelligentsia in Lviv, Kharkiv, and Kyiv, where they found themselves among avid supporters of the Ukrainian socialist-and national-democratic movements. Ethnic Ukrainians reciprocated. Panteleimon Kulish, for example, supported Kesar Bilylovskyi, who was of Jewish descent, and thought highly of his lyrics, some of which became popular Ukrainian songs. Likewise, Ivan Franko supported Grigorii Borisovich Kerner, who wrote under the pseudonym Hrytsko Kernerenko. Bilylovskyi sought to integrate Oriental and Jewish motifs within his Ukrainian prose and poetry. Kernerenko wrote several poems about Taras Shevchenko and essays on the Ukrainian national bard's poetic legacy, which, however, the tsarist censors found too suggestive and banned from publication. Nevertheless, Kernerenko persisted and is now remembered as the first to consider the fate of Ukrainian philo-Semitism and to coin images of Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement in poetic form.

In post-revolutionary Soviet times, many more Jewish writers, scholars, and cultural activists chose Ukrainian as their language of literary expression. Particularly salient among them were the poets Ivan Kulyk, Leonid Pervomaiskyi, and Naum Tykhyi; the playwright Leonid Yukhvid; the prose writers Natan Rybak and Yukhym Martych; the historian and philologist Osyp Hermaize; the literary historians Ieremia Aizenshtok and Oleksander Leites; and the musicologists Abram Gozenpud and Moisei Beregovskii.

The 1920s, in particular, were years of highly fruitful cooperation between Ukrainian literary figures of different ethnicities. The head of the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture, Yoysef Liberberg, lectured at Kyiv University in what one of his students described as a "fine Ukrainian language." The critic and scholar of comparative literature Oleksandr Leites and the Yiddish writer David Feldman were instrumental in establishing an innovative literary group which brought together writers of Ukrainian and Jewish origin committed to a new vision of socially engaged proletarian art, a trend that they called vitayism — active romanticism. Many of these literati and scholars not only shared their enthusiasm for the policy of Ukrainianization, they also took to the same stage at the Blakytnyi House of Writers in Kharkiv, which was used for literary recitals and "cold readings." Many even lived in the same residences, the best known of which was the Kharkiv House of Writers (Slovo), where more than sixty poets and novelists shared accommodations under the same roof in a large apartment building (for example, Pervomaiskyi, Sosyura, Kvitko, Fininberg, and Tychyna).

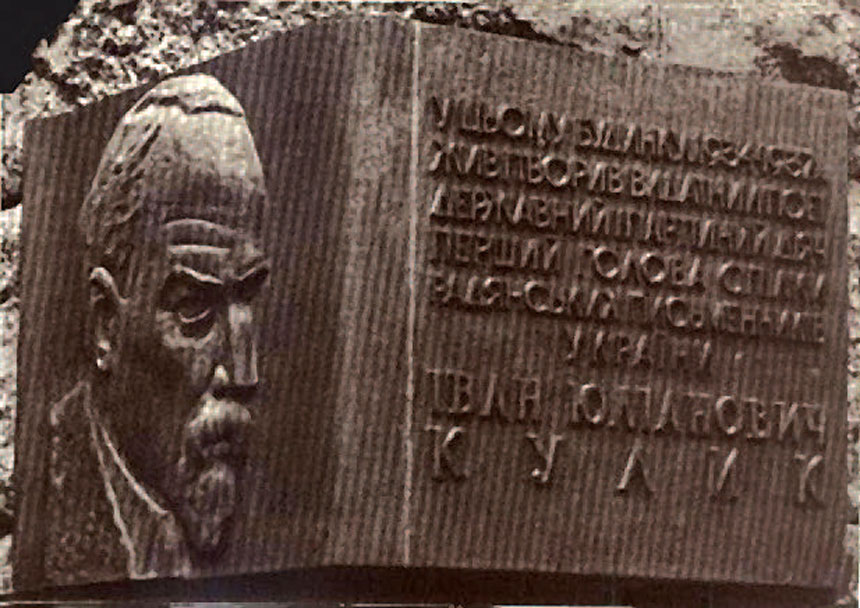

One of the most influential Ukrainian poets of Jewish descent during this period was Ivan Kulyk (b. Yisrael Iudovych Kulik). At a young age before World War I, he had fallen in love with all things Ukrainian. He eventually wrote in Ukrainian four books of poetry, two volumes of narrative prose, and innumerable journalistic essays in socialist-oriented American, Canadian, and Soviet Ukrainian newspapers, and he compiled the first Ukrainian anthology of American poetry (1927). For the Bolshevik utopian Kulyk, the very existence of post-revolutionary Soviet Ukraine, in whose government he served, symbolized his country's liberation from colonial oppression. In that context Ukrainian represented the language of national revivalism and proletarian emancipation. Kulyk's Ukrainocentric (and eccentric) Communist utopianism could not survive the right-wing turn of Stalin's Soviet Union, however. In the 1930s, he was arrested, accused of Ukrainian nationalism, and shot. But before this happened, he encouraged and supported several young poets and writers, among them two of Jewish descent, Savva Holovanivskyi and Leonid Pervomaiskyi.

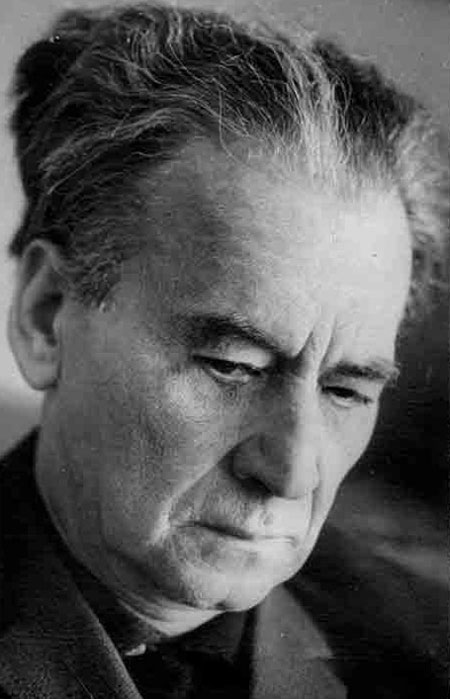

Leonid Pervomaiskyi (born Illya Shliomovich Gurevich) started his career as a Ukrainian writer aspiring to the fame of Isaac Babel. In a collection of short stories (Den novyi/The New Day, 1927), a novel (Zemlya obitovana/The Promised Land, 1927), and a play (Mistechko Ladenyu/The Ladeniu Shtetl, 1931–34), Pervomaiskyi portrayed the encounter of traditional Jews from a godforsaken shtetl in the middle of nowhere with ethnic Ukrainians and their culture. His ordinary Ukrainians and Jews become victims of the historical calamity that underscored their common tragic fate and shared suffering. Subsequently, the Holocaust became an important theme in Pervomaiskyi's writings, although he had to give it a universalistic spin in order to get through Soviet censorship and into publication. He is perhaps best known for having created unparalleled images of a poet, poetic books, and poetic language, all of which he presented as victimized and neglected living beings. In short, he saw his mission as a writer to give each of these elements a voice and thereby redeem them from oblivion. Pervomaiskyi's last three collections of poetry (Drevo Piznannya/Tree of Knowledge, 1971; Uroky poezii /Lessons of Poetry, 1968; and the posthumous Vchora i zavtra/Yesterday and Today, 1974) fascinated readers both in and beyond Ukraine, revealing that, in contrast to his more renowned contemporaries, he was growing qualitatively to such a degree that he was named by diaspora critics as one of the best Ukrainian lyricists ever.

Jewish literary figures whose careers began after the 1960s Thaw shared with their Ukrainian counterparts sympathy toward the idea of a national revival. Among them were young poets of Jewish descent who first wrote in Russian but who then switched to Ukrainian, such as Leonid Kiselev, Moisei Fishbein, and Hryhorii Falkovych. Yet another, Mar Pinchevsky, also chose Ukrainian, eventually becoming a brilliant translator into Ukrainian of European and American literature. Perhaps the most interesting among these figures is Moisei Fishbein from Chernivtsi in far western Ukraine. In 1974 he published a book of poetry (Yambrove kolo/ The Iambic Circle) that combined the Ukrainian lyricist tradition with Austrian philosophical poetry. So dedicated was the poet to his mission that he proclaimed himself the redeemer of the Ukrainian language. Aside from several other collections of Ukrainian-language poetry and translations of German literature (notably Rilke) into Ukrainian, Fishbein is, despite his eccentricities, someone who has in public and private consistently fought against the russification of Ukrainian culture, doing so in a manner that borders on messianic self-abnegation. In the late Soviet period, Jewish-Ukrainian cross-fertilization moved beyond the realm of literature. While Jewish intellectuals chose Ukrainian as their literary means of expression, Ukrainian intellectuals began to defend Jews and, at the same time, learn from the Jewish experience. Ukrainian philologist Svyatoslav Karavanskyi publicly spoke out for the right of Ukraine's Jews to have national minority schools, while Jewish dissidents imprisoned in the gulag (such as Semen Gluzman) learned "how to be Jewish" from interaction with fellow inmates of ethnic Ukrainian background, especially those (Zynovii Antonyuk, Myroslav Marynovych, Yevhen Sverstyuk, among others) of strong Ukrainian national convictions. There were also Jewish dissidents such as Mikhail Heifets who helped preserve the poetry of Vasyl Stus and have it smuggled out of a correction colony for eventual publication abroad.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.