Chapter 7.3: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 7.3

Theater

Ukrainian theatrical life

The origins of formal theatrical performance in Ukraine date back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and are connected with theological seminaries and colleges. Students, often seminarians studying for the priesthood, performed school plays whose content was both religious and secular in nature. Among the most popular were nativity plays telling the Christmas story and the birth of Jesus Christ. This genre was performed not only on school stages but also in a more spontaneous manner among villagers each mid-winter season. Secular plays included historical tragicomedies, the most memorable of which depicted the exploits of the tenth-century Rus' grand prince Volodymyr (published in 1705), by Teofan Prokopovych, and the seventeenth-century Cossack Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (1728), by Teofan Trofymovych. As representative of the Baroque era in Ukrainian literary development, the school plays were often produced with elaborate stage decorations, costumes, and special effects, and in a formal language that was a variant of liturgical Church Slavonic, not the spoken vernacular.

At the end of the eighteenth century, school plays had gone out of fashion, and after 1780 they were even banned at the influential Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. About the same time, wealthy nobles in Ukraine formed theatrical troupes made up of serfs on their landed estates. Several palatial manor houses even had their own theaters, where it was not uncommon for the landowner himself to direct the performances. These were usually drama, opera, or ballet by foreign authors and composers. The tradition of the serf theater, which was a kind of diversion for the country's wealthy social stratum, continued well into the nineteenth century, even after the abolition of serfdom in 1861.

The staging of theatrical productions for a paying public in urban settings also had its beginnings in 1780s, first in Kharkiv and by the 1820s in Poltava and several other towns in eastern Ukraine. The repertoire consisted of plays in Russian, whether original works or translations of foreign authors. It was in reaction to the predominance of Russian that the author of the first modern literary work in the Ukrainian vernacular, Ivan Kotlyarevskyi, wrote two original plays in Ukrainian, Natalka Poltavka (The Maiden Natalka from Poltava) and Moskal-Charivnyk (The Muscovite Wizard). Both were staged in 1819, the first as an operetta, the second as a vaudeville show.

Kotlyarevskyi's Natalka Poltavka set a precedent for a whole host of subsequent original stage productions which, because they draw heavily on romanticized peasant folk traditions, could be characterized as ethnographic populist theater. In contrast to the Church Slavonic school-play tradition and the largely Russian-language repertoire of foreign works that dominated the stages of the early urban-based theaters, playwrights writing in the so-called ethnographic style found their subject matter in Ukraine. The most popular subjects were stories about village life in the present or historic tales from the past, in which the dialogue was in vernacular Ukrainian and accompanied by folksongs and dances.

Comedies about daily village life, especially the tribulations of young lovers intent on marriage, or about Christmas Eve celebrations, or about the fate of the region's remaining Cossacks soon became the staple repertoire of Ukrainian-language theater. The most famous work in this genre, which is repeatedly performed to this day as a kind of quintessential representation of traditional ethnic Ukrainian life, is the play with music Zaporozhets za Dunayem (The Zaporozhian Cossack Beyond the Danube, 1863), by Semen Hulak-Artemovskyi. This work was the first to portray the longing of diaspora Ukrainians for their homeland, and its use of folkloric themes became a staple component of the Ukrainian operatic repertoire for years to come.

The era of ethnographic theater reached its apogee in the second half of the nineteenth century. Paradoxically, this was the very time in the Russian Empire when tsarist decrees (1863 and 1876) banned publications and performances in Ukrainians, the language that the tsarist regime condescendingly dubbed the Little Russian dialect. In the 1880s, when the authorities rescinded some of the restrictions, performances in Ukrainian were again possible, as long as the theatrical bill at any one time included a work in Russian that was equal in length to the one in Ukrainian. Moreover, tsarist censors also limited the kinds of themes that could be treated, allowing comic and innocent tales of village life but banning any discussion of urban life, social conflicts, or the glories of Ukraine's historical past.

By the 1890s, there were thirty troupes performing Ukrainian-language plays on a consistent basis not only throughout Ukrainian lands in the Russian Empire but also in the imperial capital of St Petersburg, where Ukrainian-language productions were viewed by the imperial elite as a somewhat exotic and certainly quaint rural antidote to life in the big city. The success of Ukrainian-language theater in the Russian Empire was due largely to a group of highly talented individuals, each of whom could be, at one and the same time, a playwright, director, manager, and actor. The most prominent of them, whose names grace several present-day theatrical institutions in Ukraine, were Marko Kropyvnytskyi, Mykhailo Starytskyi, Mariya Zankovetska, Mariya Sadovska-Barliotti, and the three Tobilevych brothers, each of whom used a different stage name: Ivan Karpenko-Karyi, Mykola Sadovskyi, and Panas Saksahanskyi.

In effect, at a time when Ukrainian-language publications were legally banned in the Russian Empire, it was only on the stage that Ukrainian could function in the public sphere. Such theatrical performances were undoubtedly popular, because ethnic Ukrainians could at least feel that their otherwise often scorned "kitchen dialect" could still have a place of respect on the stage, if nowhere else.

In the more tolerant nineteenth-century Habsburg-ruled Austro-Hungarian Empire, theater was one of several means whereby the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) language and national identity could be propagated. Beginning already in 1864, Galicia was home to a professional theater, that of the Ruthenian Speech Society/Ruska Besida, which focused exclusively on performing works in the local Galician-Ukrainian vernacular, whether its actors may have been Ukrainians from the Russian Empire or even Poles from Galicia. The repertoire consisted of plays by regional authors, the most prominent being Ivan Franko, as well as adaptations to local Galician conditions of Ukrainian-language works by authors from the Russian Empire. It was through such theatrical performances that Galicians and Bukovinians learned about and gained a greater cultural affinity toward their co-nationals in the east.

The collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917 and the end of restrictions against the Ukrainian language gave the Ukrainian theater a new lease on life. With the establishment of Soviet rule in 1920, the state took over the direction of cultural institutions, which were henceforth subject to the needs of Communist party ideologists. When, beginning in 1925, the policy of Ukrainianization was implemented with vigor, major theaters in urban centers, where Russian-language performances had been the norm, were now ukrainianized. Within a few years (1931), the number of Ukrainian theater companies stood at sixty-six in comparison with only nine Russian companies, which was even less than the number of Yiddish companies (twelve) in Soviet Ukraine at the time. When, however, government attitudes toward Ukrainianization changed, many Ukrainian theaters were closed at the same time that the number of Russian theaters increased threefold (to thirty by 1935).

Soviet government policy also had an impact on the repertoire. During the relatively more liberal atmosphere of the 1920s, the heritage of the Ukrainian ethnographic theater with its emphasis on village life and Cossack themes was rejected by avant-garde playwrights and producers who instead were interested in modern experimental theater, in particular contemporary Expressionist works from western Europe and North America. Among the more influential modernist dramatists were Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Mykola Kulish, whose plays satirized the glaring contradictions between Ukrainian national aspirations and the new Soviet reality. The production of plays by these and other authors was made possible by innovative artistic directors, of whom the most successful was Les Kurbas of the Berezil Theater in Kyiv and Kharkiv (during the decade from 1922 to 1933). Aside from its modernist orientation, the Berezil was committed to performing in Ukrainian.

Another trend, particularly characteristic of the 1930s, was one that fulfilled the practical needs of the state's cultural ideologists. It consisted of plays, also in Ukrainian, which lavished praise on the new Communist social order. Heroes and heroines were now class-conscious and confident proletarian workers, not downtrodden peasants — so prominent in the ethnographic theater — who seemed always powerless to defend themselves against the whims of feudal landlords and the repressive measures of the old tsarist empire.

When, in the 1930s, the Soviet system itself had become even more repressive than its Russian imperial predecessor, and when artistic productions were expected to fulfill government guidelines under the general rubric known as socialist realism, the Ukrainian ethnographic repertoire was revived. These were the creative principles that characterized Soviet Ukrainian theatrical life for the next half-century until well into the 1980s. Traditional rural life and select events from the historic past, especially those that could be reinterpreted or revised to depict social uprisings among the masses, were considered by the regime acceptable and even desirable themes. And it was not long before serious new dramatic works as well as foreign plays from the classic repertoire — so-called high culture — became the domain of Russian-language productions. Meanwhile, the ethnographic "low culture" repertoire from the nineteenth century, together with optimistic socialist-realist dramas inspired by contemporary Soviet life by authors like Oleksandr Korniichuk, were deemed most appropriate for Ukrainian-language productions.

Thus, while Ukrainian-language theater continued to exist until the very end of Soviet rule, it never attained the prestige accorded its Russian-language counterpart. In post-1991 independent Ukraine, theatrical life is still characterized by the same kind of high-culture/low-culture dichotomy that underlies the often uneasy relationship between supporters of the Ukrainian versus the Russian language as the most appropriate instrument to represent the country's cultural and intellectual life.

Jewish theatrical life

The beginnings of Jewish theater in Ukraine can be traced back to early modern times and to the folk play genre called the Purimshpil. This was the only type of theatrical performance endorsed by the community's influential rabbinic authorities. The Purimshpil was based on events recorded in the biblical Book of Esther but modernized to include references to contemporary socio-political life and performed — usually in Yiddish — during the holiday of Purim in late winter or early spring.

With the subsequent secularization of eastern European culture, new types of Jewish theater came into being. Traveling amateur troupes staged the so-called shund (trash), soap-opera-like melodramas albeit with palpable social criticism. The performers traversed the breadth and width of Ukrainian lands in the Russian Empire and, in particular, Habsburg-ruled Galicia. The pioneer of this new type of the Jewish theater, Avrom Goldfadn, was a native of Russian-ruled Ukraine who worked in both empires until he left the tsarist realm permanently. One of the reasons for his departure was the Russian imperial ban on Yiddish-language theatrical performance that was put in place in the 1880s. By contrast, in Austria-Hungary, Jewish theatrical troupes functioned without restriction and performed widely throughout Galicia and Bukovyna, staging the popular melodramas by Shomer (pseudonym of Nokhem Shaykevitch) and the more serious plays with social and historical underpinnings by Sholem Ash and Jacob Gordin.

Although the vast majority of theatrical performances were for internal Jewish consumption, there were cases of interaction between Jews and the larger Ukrainian public. In the 1880s, Hrytsko Kernerenko penned a Ukrainian vaudevillian drama of the shund style for a theater in Kharkiv, while at the outset of the twentieth century the Ukrainian novelist Yurii Smolych mastered Yiddish and performed with itinerant Yiddish theatrical troupes across Ukraine.

This era of innovative exchange and artistic cross-fertilization in various spheres between Ukrainian and Jewish theater continued with the establishment on the eve of World War I of the Kultur-Lige (Yiddish Culture Society). This Kyiv-based Jewish organization had its own experimental theater troupe, staging short plays with strong messianic ideas whose goal was to replace a narrowly Jewish ethnic message with a more broadly appealing cultural one. The troupe's director, Efraim Loyter, considered pure and unrestricted artistic transnational experiment to be the most powerful expression of the revolutionary Yiddish identity.

In Soviet Ukraine during the 1920s, the authorities planned to create a new proletarian Jewish theater capable of bringing socialist ideas to the masses. Toward that end, the government sponsored the creation of a system of state Yiddish theaters throughout the country. Mainstream Jewish theater began at the moment the ruling Communist party moved the Soviet republic's capital to Kharkiv and created there in 1925 the Ukrainian State Yiddish Theater. Drawing on traditional Yiddish culture, the theater used visual symbolism and expressive body language to make its performances truly international and all-encompassing. Whatever the literary value of Yiddish theatrical repertoire may have been, the overall artistic quality of Jewish theater in Soviet Ukraine was quite high. The illustrious actor Solomon Mikhoels, the director of the Ukrainian State Yiddish Theater, Efraim Loyter, and the founder of the Ukrainian-language Berezil Theater, Les Kurbas, collaborated and shared their modernistic innovations during their highly productive Kharkiv period. Several other ethnic Ukrainian actors either started their careers or worked through the 1920s and 1930s at Yiddish theaters in Vinnytsia, Odessa, Kyiv, and Zhytomyr. Aside from the stylistic experiments and the professionalism of actors, Yiddish theaters had their own orchestras, with music and songs composed by a new generation of Ukrainian Jewish composers. The career of someone like Yakov Vynokur was not atypical. He first worked as a bandleader (Kapellmeister) in the Russian imperial army, then headed the Red Army Orchestra before becoming music director of the Ukrainian State Yiddish Theater.

The repertoire in the 1920s and 1930s included plays by the outstanding Yiddish writers Perets Markish and Dovid Bergelson. And while their and other works reflected a largely Marxist worldview, they nonetheless remained sensitive to the classical Yiddish legacy embodied in the popular pre-revolutionary melodramas of Avrom Goldfadn and Jacob Gordin. Theater directors and actors believed that they were contributing to the creation of a genuinely international revolutionary art — and to emancipated Ukrainian culture in general. While their new theatrical art was in Yiddish, it used the imagery and artistic vocabulary of the revolutionary avant-garde, enabling it to reach everyone.

This high-spirited utopianism received its first blow in the early 1930s, when Kharkiv's State Yiddish Theater was moved to Kyiv. Under politically motivated ideological pressure, the company was forced to change its artistic approach from a leftist and experimental orientation to one that was more traditional and realistic. The theater also had to drop its Maccabee-like celebration of Jewish heroism (such as Kushnirov's "Hirsch Lekert," about a Jewish terrorist who attempted to kill a repressive tsarist provincial governor), since attacks against state authorities were no longer considered praiseworthy. Plays of the new repertoire, whether by younger Soviet Jewish writers (Ezra Fininberg, Itsik Fefer, Avrom Vevyorke, Moyshe Kulbak, Moyshe Pinchevsky) or by more established ones (Perets Markish), were filled with tales about former shtetl Jews who went to rural areas to build collective farms as new Soviet peasants or descended below the land to learn the métier of miners and hence become Soviet proletarians.

In the late 1930s, Yiddish theater in Ukraine got, so to speak, a second wind as new personnel joined various troupes. These were graduates of the Jewish Department of the Kyiv Theatrical Institute that was established in 1928. They had come from various places throughout Soviet Ukraine and after their professional formation joined Ukraine's State Yiddish Theater or Kyiv's newly established Jewish Puppet Theater, as well as other Yiddish troupes in Soviet Ukraine.

Yiddish theaters always performed to a full house. To be sure, in the class-conscious environment of early Soviet society, actors always poked fun at wornout Judaic beliefs, mocked the representatives of the rabbinic elite, and satirized all aspects of the traditional way of life. Nevertheless, people came to the theater to celebrate the very fact that a Jew was not only onstage but on the stage of a national theater. This was an artistically fascinating and socially uplifting achievement of the new regime that was unheard before the Revolution of 1917. Consequently, spectators dismissed the sometimes very painful anti-Judaic invective and instead identified with the Yiddish language, with Jewish names, and with familiar visual metaphors and symbols — in general, with any manifestation of Jewishness. At a time in the 1930s when the Soviet regime launched its aggressive campaign to sweep away many of the cultural and political achievements of the previous decade, for Ukrainian Jews theater remained a unique medium where they could reconfirm and rejoice in the celebration of their own Jewish identity.

The Ukrainian State Yiddish Theater, which suffered heavy losses during World War II, was allowed to re-establish itself at the end of the conflict. By then, when the Cold War was in its initial stages, the Soviet authorities preferred to reopen the theater not in Kyiv but in the far western provincial center of Chernivtsi, where it put on several plays from the classical repertoire, including adaptations of Sholem Aleichem and Shakespeare.

Yiddish theatrical life could not survive the post-war repressive atmosphere directed against the Jewish elite. In Soviet Ukraine the repressions began with attacks on theatrical critics (Eugene Adelgeim, Abram Gozenpud, Aleksander Borshchagovskiy), who were accused of "rootless cosmopolitanism." The government-inspired antisemitic campaign soon involved Jewish writers, in particular those who published in Yiddish. The campaign culminated in 1948 with the closure of virtually all Yiddish theaters in the Soviet Union, the very last one being the Yiddish Theater in Chernivtsi, which was permanently dismantled two years later. Despite the closures, the various theaters that functioned during the early decades of Soviet rule did provide a springboard for dozens of Jewish artists who, in the post-World War II era, were to play a significant role in Soviet Ukraine's cultural life: the composer Yulii Meitus, the actress Lia Bugova, and the conductor Natan Rakhlin, among others.

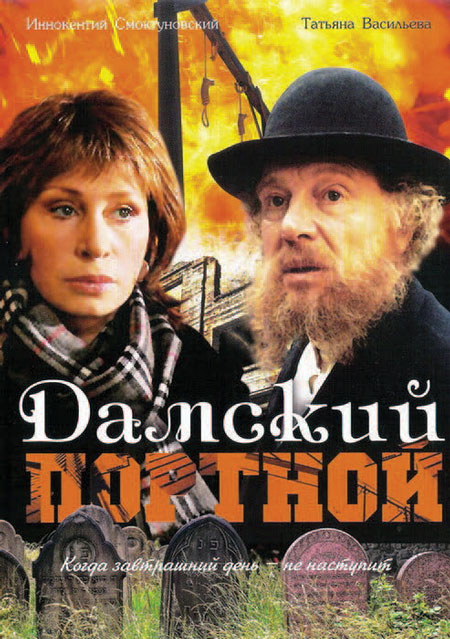

On the other hand, Jews as Jews almost entirely disappeared from the Soviet stage. While the few who did remain tried to function in the larger Soviet theatrical world, even there they encountered obstacles. For example, Alexander Galich, a converted Jew from Katerynoslav, wrote a play in Russian, Matrosskaya tishina (The Sailors' Silence Street, 1950), about the tragic fate of a Jewish violinist from Tulchyn and his strained relations with his father. The play was immediately banned and not performed until the relaxed years of Gorbachev's rule in 1988. Similarly, in the late 1970s, Aleksander Borshchagovskiy wrote a drama, The Ladies' Tailor, about a Kyivan Jewish family on the eve of the Babyn Yar massacre. It, too, was banned from performance by Soviet censorship.

Despite the cultural persecution and closure of Yiddish theaters, by the 1950s actors from the State Yiddish Theater in Chernivtsi managed to regroup as a popular Ukrainian amateur theater and stage performances of the Jewish classics, although in the Ukrainian language. Another kind of Jewish theatrical presence in the period from the 1950s through 1980s, and one that embodied interaction between Jews and Ukrainians, took the form a popular comedy act featuring Yurii Tymoshenko and Yefim Berezin, better known under their aliases, Tarapunka and Shtepsel. The success of their performances was largely due to the comic material of their Jewish-Ukrainian scriptwriters and satirists, Robert Vikkers and Alexander Kanevsky.

In the waning years of the Soviet Union and especially in post-1991 independent Ukraine, there have been several, albeit short-lived, attempts to revive Jewish theatrical life, although it has been through the medium of the Russian or Ukrainian languages, not Yiddish. Among such attempts have been amateur troupes in Kyiv (Mazl Tov), Zhytomyr (The Jewish Street), Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi (The Jester's House), and Chernihiv (The Spiegel Jewish Children's Theater). There is even a small-scale professional troupe, the Sholem-Aleichem Music Drama Theater in Kyiv, which has been performing from the mid-1990s. In a sense, the history of Jewish theatre has come full circle and has returned to its folkloric roots, so that the only mass theatrical event is now the annual Purimshpil performance during the festival of Purim. Staged at Ukraine's massive Palace of Culture in Kyiv, it attracts several thousand people every year.

Nor does the dearth of formal Jewish theatrical structures in independent Ukraine signify the absence of Jewish performances. Today productions based on Jewish themes are put on by Kyiv's Variety and Operetta Theater (the musical performance Jewish Luck), and several Ukrainian theaters have staged Neda Nezhdana's drama, Million Little Parachutes, which deals with the Holocaust period and Ukrainian attitudes to the Jewish plight. But perhaps the most important Jewish performance to grace Ukrainian stages is Sholem-Aleichem's Tevye the Milkman. Performed to great acclaim at the Ivan Franko State Drama Theater in Kyiv, the play starred Ukraine's most famous actor, Bohdan Stupka. The ethnic Ukrainian Stupka managed to capture brilliantly the character of Tevye, a shtetl-based Jewish philosopher who reads life as a book and tries to make universal ethical sense out of the incredibly humanly rich and at times tragic plight of Ukraine's Jews.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.