Chapter 8.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 8.1

Architecture and Art

Ukraine's cultural landscape is dotted with a wide range of structures that reflect the entire gamut of European architectural styles. The architects who came from abroad used building techniques and styles familiar to them in their home country, while local architects created their own versions of those styles and at times tried to devise an indigenous style unique to Ukraine. It is therefore not surprising that the stylistic vocabulary used in other parts of Europe is applicable as well to Ukraine, where there exist remnants or full-standing (often restored) structures that are described as belonging to the period of classical Greco-Roman antiquity, medieval Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic, early modern Renaissance and Baroque, Revivalism and Art Nouveau of the long nineteenth century, and modernism of the functionalist International Style in the twentieth century.

Pre-historic architectural remnants

The earliest architectural remnants in Ukraine are connected with an agricultural and cattle-raising civilization known as the Trypilian culture, which flourished between 4500 and 2200 BCE in central and southwestern Ukraine. By the latter stages of Trypilian culture, some of its settlements had up to three thousand buildings, most of which were pit or semi-pit dwellings and houses raised on wooden poles. In recent years numerous Trypilian settlement sites have been uncovered and developed into sites for cultural tourism, with the goal of revealing the high level of sedentary civilization on Ukrainian lands that dates back between four to six thousand years ago.

Much better known are the architectural remnants associated with classical Greek settlements that began to appear from the seventh century BCE and that were to survive into Hellenistic and Byzantine times at least until the seventh century CE. These settlements were concentrated in far southern Ukraine along the shores of the Black Sea near the mouths of major rivers (Tiras near the Dniester and Olbia near the Southern Buh) and on the Crimean peninsula (Chersonesus/Sevastopol and Panticapeum/Kerch). Still-standing remnants in marble and stone include columns from palaces and basilica-like churches as well as foundations of domestic dwellings usually laid out in square geometric street patterns. Rather unique is another architectural phenomenon from those early times: the cave towns in Crimea built in the sixth century CE by Byzantine engineers for that region's Alan and Goth settlers. Because those structures were carved out of durable stone on flat mountaintop promontories, they still today provide a graphic example of how inhabitants in the mountainous regions of Crimea lived and worshipped nearly fifteen hundred years ago.

Eastern and Western church architecture

Among the structures that are still most prominent in Ukraine's cities, towns, and villages were those built for religious purposes, whether Christian churches, Jewish synagogues, and, especially in one region, Crimea, Islamic mosques. Most of Ukraine's church architecture, however, was built for adherents of the two major branches of Christianity — Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Each branch developed a distinct church architecture based on models, which, in the hands of a given builder, might be altered and enhanced by stylistic variations.

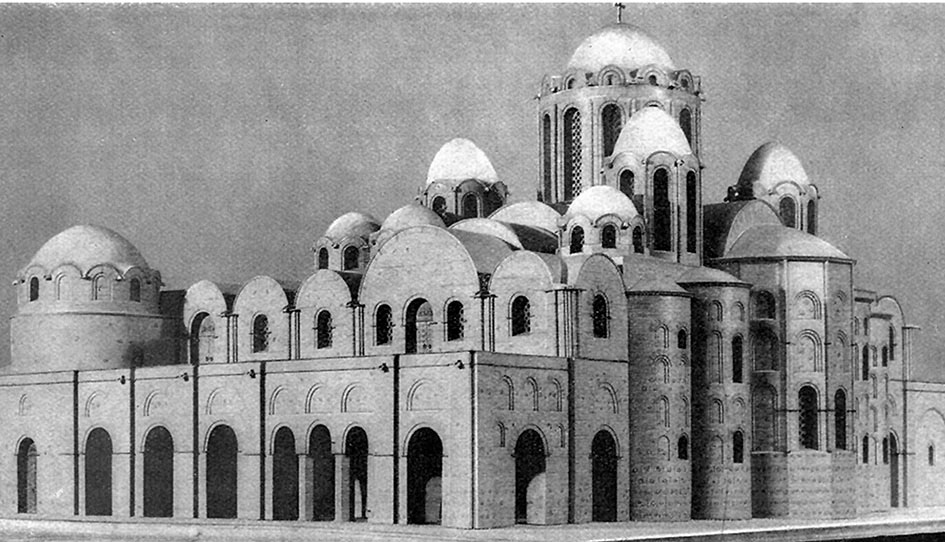

The predominant architectural form in Ukrainian lands is that used for churches belonging to the Eastern Orthodox branch of Christianity derived from the East Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. The typical ground-plans of Byzantine churches are based on a Greek-style cross with two equidistant arms; sometimes the cross ground-plan is within a square, the so-called cross-in-square church. The exterior is notable for domes or cupolas atop cylindrical drums placed over the four ends of the Greek cross with a fifth large dome or cupola over the central point of the cross. Ideally, the domes or cupolas are sheathed in gilded metal, and in more recent centuries have been topped with three-bar crosses.

Eastern church interiors have only limited external light, since the walls are usually pierced by small windows. The extensive indoor wall surfaces are covered with fresco paintings and/or gilded glass mosaics depicting the founding fathers of Eastern Christianity and other Orthodox saints, with the image of Christ given pride of place either above the altar or in the central dome. The dominant interior element located below the central dome is the iconostasis, a tall screen with several rows of painted images (icons) depicting major church figures. At the ground level of the iconostasis, on each side of its royal doors (tsarski vrata) in the center, are the icons of Mary, the Mother of God, Christ, John the Baptist, and the saint — often connected with a local religious cult — to which the church is dedicated. The three or four rows above contain smaller icons that depict the apostles, saints and martyrs, prophets, and, at the top, Hebrew patriarchs of the Old Testament.

The exterior and interior look of Western churches differs considerably from that of Eastern churches. The basic Western church structure evolved from the classic Roman basilica, an oblong structure at one end of which is a transept ending in semi-circular apse. The ground plan is reminiscent of a stylized Western cross. The interior consists of four basic components: at the western end — an entry hall, or narthex; then the main sanctuary for the congregation, consisting of a long nave with one or more flanking aisles on each side; the transept, in the middle of which is the altar; and at the eastern end the apse, usually reversed for high church figures (hierarchy) and the choir. The nave is filled with movable or stationary seating (in contrast to Eastern churches where worshippers stand), flanked by side aisles that may have individual chapels, prayer areas, and booths for individual confession along the outside walls. The walls themselves may be adorned with paintings or statues and pierced by large windows, ideally with colored stained glass.

The exterior usually has a pitched roof, with perhaps a narrow spire over the center of the transept, that is, at the point where the altar is located inside. The main entrance at the western end may be topped by one bell tower or be flanked on each side to form a two-tower façade. The exterior walls and the portal surrounding the main west entrance may be adorned with statuary.

This standard architectural model for the Western church was epitomized in the Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals of medieval France with their complex stone-carved rounded or pointed arches, high-ceiling interiors, and, in the case of Gothic churches, flamboyant exterior "flying" arches whose functional purpose was to support the walls of the nave while also illuminating the interior with natural light filtering through large expanses of stained-glass windows. The Gothic was also used for churches in central and some parts of eastern Europe, although in Ukraine the few examples that exist were built much later in a Neo-Gothic style, including large cathedral-sized churches for Roman Catholic Poles living in Kyiv (1899–1909) and Lviv (1903–11).

Eastern church architecture derived from Byzantium is connected with the period of medieval Kievan Rus'. The most important examples in Ukraine include St Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (1017–1050s) and the Cathedral of Saints Borys and Hlib in Chernihiv (late twelfth century). The St Sophia Cathedral was architecturally unique for its number of domes (thirteen), although it, like many other churches from the Kievan period, underwent significant restoration after the seventeenth century as a result of which the oval domes characteristic of the Byzantine style were reshaped into pear-form Baroque cupolas. St Sophia's interior, on the other hand, does retain the original magnificent gilded mosaics and fresco wall paintings. The architectural value of the Saints Borys and Hlib Cathedral in Chernihiv is that, despite subsequent restorations, the external form is basically the same as it was when completed in the late twelfth century.

Ukraine's architectural monuments

The architecture of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, a time when Ukrainian lands were for the most part within the Polish-Lithuanian and Crimean political spheres, reflects two trends: (1) influences from western Europe via Poland into Galicia and Volhynia and via Italianate Genoa and Venice into Crimea and the Black Sea coastal region; and (2) efforts by local architects to adapt or superimpose on to western prototypes features that are indigenous to Ukraine.

The first trend is particularly evident in western and Black Sea Ukraine's many surviving castles (Khotyn, Lutsk, Mezhybizh, Kremenets, Kamyanets-Podilskyi, Mukachevo, Stare Selo near Lviv, Bilhorod near the mouth of the Dniester River, Sudak in Crimea), fortified churches (Sukhivtsi, Ostroh, Rohatyn), and defensive walled monasteries (Mezhyrichchya, Zymno). These were usually based on models from western and central Europe and included Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque elements in their design. Such influences were even more evident in urban architecture, especially in what was at the time Polish-ruled Lviv, with its Renaissance-style Black House (1577) and Korniakt Palace (1580) facing the main square, the nearby Eastern-rite Church of the Assumption (1598–1631) with its adjacent belfry "tower of Korniakt" (1573–78), the Roman-rite Catholic Church of the Bernadine monastic Order (1600–30), and the late Renaissance/Mannerist Boim Family Chapel (1607–17).

The Baroque architectural style, originally connected with the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation, began to appear in Ukrainian lands in the second half of the seventeenth century. It was largely based on the Baroque architecture of Poland that was welcomed by urban-based Orthodox lay brotherhoods and, in particular, by the leaders in the Cossack Hetmanate state based in central Ukraine. Cossack officials, in particular Hetman Ivan Mazepa, were attracted to the grandeur and sumptuousness of Baroque façades and interiors. Local architects also made use of indigenous design elements, especially in buildings intended for the administrators of the Cossack state. Among the few surviving examples of this architecture is the early-eighteenth-century Lyzohub Regiment Office in Chernihiv. Architects also added Baroque elements to the exteriors of Eastern-rite Orthodox churches, in particular faux pedimental façades, decorative columns, and sculptured wall designs surrounding the windows and entranceways (Dormition Church at the Caves Monastery in Kyiv, rebuilt 1720; Mhar Monastery Cathedral in Lubny, 1684).

The Cossack Baroque style, as it came to be known, reached its apogee during the rule of Hetman Mazepa (r. 1687–1709), who alone is credited with funding the restoration or constructions of twenty churches, mostly in Kyiv, including the Church of Epiphany of the Brotherhood Monastery (1690) and St Nicholas Cathedral (1696). The most impressive reconstruction project was that undertaken for the eleventh-century Church of St Sophia, whose exterior was entirely transformed (1691–1705) into the Baroque-looking cupoled edifice that remains today a hallmark of Kyiv's old city center. The post-Mazepan era's search to build in a style unique to Ukraine was dominated by the architect Ivan Barskyi, whose works, mainly in Kyiv, combined the traditions of the Cossack Baroque with stylistic influences from the later Rococo, whether in Eastern-rite churches (St Cyril Monastery Church, rebuilt 1760; Church of the Holy Protectress in the Podil district, 1766) or in municipal public works (the pavilion-like Felitsiial — Samson's Fountain, 1748–49).

Notably imposing are western Ukraine's Roman Catholic churches in the Baroque style, with their undulating façades, half pediments, expansive open interiors, lavish external and internal statuary, and ceiling paintings illuminated with an ingenious use of redirected external natural light. These features are evident not only in Lviv's churches for the Roman Catholic Dominican monastic order (1745–49) and St George's Church (1745–60), which were refashioned with Rococo influence to serve Eastern-rite Catholics (see illus. 119 and 120), but also in other centers of Roman Catholic Polish culture, such as the Collegial Church in Kremenets (1730s–1740s) and the Eastern-rite church at the monastery in Pochayiv (1771–83), redesigned at a time when it had become Uniate Catholic.

Some late-eighteenth-century buildings incorporated elements of the Rococo style, with its fanciful curved spatial forms and shellwork ornamentation that provide an overall sense of lightness that is in stark contrast to the heaviness of the Baroque. The best examples of Rococo in Ukraine were all constructed by foreign architects: the City Hall in Buchach (1751) by Bernard Merderer-Meretini; and, in Kyiv, St Andrew's Church (1747–53) and the imperial palatial residence (1747–55), by Bartolomeo-Francesco Rastrelli. The latter, known as the Mariynskyi Palace, functions today as the official residence of Ukraine's presidents.

Another type of structure, one especially reflective of indigenous Ukrainian architecture, was the wooden church with its separately constructed belfries nearby. Although wooden churches are usually associated with the forested Carpathian region in far western Ukraine (southern Galicia, northern Bukovina, and Transcarpathia), they were also built throughout central and northeastern Ukraine. While in the Carpathian region the standard format was a single-frame low structure with three component parts each covered by sloping or bulbous cupolas, those farther east were multi-framed structures much taller in size, with each of the five or more frames in the form of barrel vaults topped with domed cupolas in the Cossack Baroque style. The largest of these wooden structures had seven frames (Church of the Ascension in Berezna, Chernihiv region, 1761) and even nine frames (Holy Trinity Church in Novoselytsya/Novomoskovsk, Dnipropetrovsk region, 1755–78) averaging 37–38 meters/103–125 feet in height.

The architecture of the long nineteenth century (1780s–1914) was characterized throughout Europe by Revivalism, that is, choosing a past style to copy or to adapt, when necessary, to contemporary needs. The first of the revivalist styles to make its way to Ukraine was Neo-classicism, with its emphasis on clean vertical lines defined by the use of columns reminiscent of Greek and Roman temples of antiquity. An early harbinger of Neo-classicism was the main bell tower of the Kyivan Caves Monastery (1731–45), whose architect, Johann Gottfried Schaedel, still included Baroque elements in his structures. Full-fledged examples of Neo-classical structures were the St Vladimir University of Kyiv (1837–43), designed by the local architect Vincent Beretti, and the Ossolineum Polish National Foundation, today the Stefanyk Library in Lviv (1826–44), designed by the Viennese architect of Swiss origin, Peter Nobile.

Perhaps the most impressive examples of Neo-classicism were to be found not in cities but rather in the palatial architecture of the rural countryside. These include several projects for the last hetman of the Cossack state, Kyrylo Rozumovskyi. The grandest of these is at Baturyn (1799), designed by the British architect Charles Cameron (see illus. 21). As impressive were the monumental-sized palaces on the manorial estates of Polish landlords, especially in the Right Bank provinces of Volhynia and Podolia: the family palaces of the Potockis at Tulchyn (1781–82); the Ksawerys at Voronevytsya (1780–90); and the Sanguszkos at Slavuta (1782–86). The places of Polish aristocrats were more often than not surrounded by elegant parks, whose layouts were inspired by Romanticism and filled with Neo-classicist sculpture and structures (pseudo-Greco-Roman temples, colonnades, grottos). Parks from this period that today continue to attract thousands of visitors include the Sofiyivka in Uman and the Oleksandriya near Bila Tserkva. Another palace from this period, but one in a non-Euro-pean revivalist style, is the reconstructed residence of the khans (1740s) at Bakhchysarai in Crimea.

Virtually every revivalist style in nineteenth-century Europe is represented in Ukraine. These include Neo-Byzantine Eastern-rite churches; Neo-Gothic Roman Catholic churches for urban Poles or simplified versions for rural ethnic Germans; and Viennese Neo-Renaissance opera houses in Lviv, Chernivtsi, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, and Kherson. There were as well a wide array of Revivalist-style government buildings, schools, museums, residential apartment blocks, banks, private company office headquarters, and railroad stations in major cities and even at some provincial rail junctions (Zhmerynka). Although making use of the latest technological advances in design and construction materials, these elements were structurally integrated and hidden behind walls and façades that combine the full gamut of Revivalist styles, from Neo-Gothic and Neo-Renaissance to Neo-Baroque and Neo-classicism.

As the long nineteenth century drew to a close, architects on the eve of World War I set out to devise a style that would not be dependent on a revivalist aping of the past but rather embody what they considered a genuine Ukrainian style that incorporated features characteristic of folk architecture into modern buildings. The leading figure in this movement, Vasyl Krychevskyi, created a series of unique structures including the Land Administration/ Zemstvo Building, now the city museum in Poltava (1903–06), as well as a series of residential and civic buildings throughout Ukraine's cities. The first decade of the twentieth century brought Art Nouveau to Ukraine, which resulted in a whole series of stunning residential and civic structures, especially in Kyiv, of which the truly extraordinary are by the Ukrainian-born Pole from Podolia, Leszek Dezidery Gorodecki/Vladyslav Horodetskyi (the Karaite Kenasa, 1898–1902; and the House with Chimeras Building on Bankova Street, 1901–03).

Architecture in Ukraine continued to remain in step with trends in the rest of Europe during the first decade of Soviet rule in the 1920s. Functional constructivism, which was the hallmark of the International Style pioneered in Germany, was eagerly welcomed by architects in Soviet Ukraine. "Form follows function" was the clarion call of the International Style. Therefore, the newest building materials (especially steel and high-resistant glass) were used, but without any decorative elements which were considered superfluous to the structure, not to mention ideologically old-fashioned and symbolic of the feudal-bourgeois-capitalist world that the Soviet regime set out to bury forever.

Buildings in the International Style were usually part of large-scale urban-renewal projects intended to modernize Soviet cities. The best-known examples of the new revolutionary architecture were the State Industry Building Complex (1925–29) and Main Post Office (1927–29) in Kharkiv, which at the time was Soviet Ukraine's capital; the Main Railway Station (1927–33) and the House of Doctors (1928– 30) in Kyiv; and the Dnieper Hydroelectric Station (1927–32) near Zaporizhzhya.

In the early 1930s, when the Soviet authorities imposed socialist realism as the guiding principle for state-controlled and censored artistic endeavor, the functionalist International Style was banned. In its stead, architects were expected to design in an officially accepted style. This was an eclectic revivalist hodgepodge of Classicism, Renaissance, Baroque, and some elements of Constructivism, which were combined in varying proportions to achieve an ideological purpose: to convey through the grandeur and monumental look of buildings the power and authority of the Soviet state.

Throughout Ukraine there are examples of officially approved architecture from the late 1930s in structures intended for a wide variety of purposes, such as the Opera and Ballet Theater (1933–40) and the Shevchenko Movie Theater (1933–38) in Donetsk, the Theater in Dnipropetrovsk (1941), and the Dynamo (1934–35) and Central (1937–41) sports stadiums in Kyiv. The pretentiousness of these and other buildings was sometimes dubbed the Stalinist wedding-cake style, after the main building of Moscow State University (1949–53), which was later copied in major Soviet cities (Kyiv's version is the old Moscow, now Ukraine, Hotel) and in many of the former Communist satellite capitals in central Europe.

After 1936, when Kyiv again became Ukraine's capital city, historic churches (in particular St Michael's Church of the Golden Domes) and other buildings were razed to make way for grandiose projects, such as the partially completed new seat of Soviet Ukraine's government (1938), the seat of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR (1936–39, present-day Ukraine's Parliament), and the Building of the Council of Ministers (1935–37). This decidedly sterile style associated with the country's dictatorial leader at the time, Joseph Stalin, became from the 1930s the approved architectural standard throughout the Soviet Union. Attempting to imitate the early-twentieth-century skyscrapers of New York City and Chicago, it was ironically dubbed Socialist Gothic.

From the end of World War II until the demise of the Soviet Union nearly half a century later, large-scale public buildings throughout Soviet Ukraine were built either in some variant of functional constructivism or in the pompous official style with its eclectic borrowings from the past. The latter was at its best — or worst — typified by the post-war reconstruction of Kyiv's main thoroughfare, Khreshchatyk, with its Druzhba (Friendship) movie theater as the quintessential example of Socialist Gothic architecture. Most widespread, however, were the rows upon rows of undifferentiated apartment blocks in the suburbs of Ukraine's ever expanding cities. These were often built using cheap materials, with absolutely no decorative elements or even color (other than weather-stained concrete or mortar covering), which to this day define the non-descript and impersonal nature of much of Ukraine's cityscapes, most particularly in the central and eastern parts of the country.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.