Chapter 8.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 8.2

Jewish architectural monuments in Ukraine

Jewish architectural monuments in Ukraine are primarily synagogues. The oldest of these are the so-called fortress synagogues which date back to the sixteenth century. It is likely that they replaced older synagogues at the same locations from centuries before. Designed by professional Christian architects, the sixteenth-century synagogues generally are built in the form of a square with an elaborate Mannerist-style upper level adorned with stone-carved ornament and loopholes, engaged columns on all four sides, formidable U-shaped windows high above ground level, and unusually massive counterforces supporting thick structural walls. Since Jewish communities in towns at that time could afford only one synagogue, these structures were used not only as a place of worship but also as a safe haven in case of a sudden attack by enemies within or during a fire. Most synagogues were large enough to hold the entire urban Jewish community. In addition to the synagogues at Sharhorod, Sataniv, and Zhovkva, one of the earliest urban synagogues in Ukraine was the Golden Rose in Lviv, commissioned by the Jewish financier of the Polish king, Isaac Nachmanowicz, and built by the architect of Swiss origin known as Paolo the Italian in 1582.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, new synagogues were built in the major centers of Ukraine's Jewry both in the Russian Empire (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa) and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Chernivtsi and Uzhhorod). These structures were unusually large, often quite pompous, and modeled after German and Austro-Hungarian Reform temples with quite visible Oriental ornamentation known as the Moorish style.

Like the Reform Jews of central Europe, the urban and modernized well-to-do Jewish elites in Ukraine sought to disassociate themselves culturally from what they considered the ramshackle shul (prayer house) that characterized the traditional shtetl and city suburb. They also did not want to be associated with the Orthodox, particularly the Askenazic Hasidim, who epitomized the secluded and allegedly backward life of small towns in the Russian Pale of Settlement. They instead took their architectural models from the Jews of medieval Spain, who easily interacted with the surrounding Muslim culture and were not afraid of its rationalist impulses. This explains the use of the medieval Moorish style in Ukraine's new synagogues, whose architecture made a point of comparing the enlightened, urbanized Jews of nineteenth-century Europe to the well-integrated Spanish Jewry who centuries before had lived "under the crescent." Proud of belonging to an increasingly modern Russian and Austro-Hungarian society, Jewish synagogues expressed this pride through urban centrality and visibility. The synagogues in Kyiv and Odessa, funded by the business magnates of the wealthy Brodsky family, were literally a monument to this new sensibility.

The sixteenth-century stone synagogues and the Moorish-style synagogues built after the 1860s were somewhat exceptional. Most seventeenth-and eighteenth-century synagogues built in the towns Ukraine were constructed of wood and often designed by Christian architects. Synagogues such as those in the shtetls of Hvizdets, Yarmolyntsi, Kytaihorod, Minkivsti, Porytsk, and Pohrebyshche were stylistically similar to wooden Roman Catholic churches while differing from the surrounding Eastern Christian churches. The synagogues did not, however, have a central dome crowning the main hall of worship (or if they did, it was triangle-shaped); they did have an internal upper gallery or galleries around the main hall for female worshippers separated in the traditional Jewish communities from men; and they included several smaller wings which likely included a library (Heb.: bet midrash; Yid.: besmedresh) and "warm" prayer rooms for use between the High Holidays and Passover.

Many Jewish synagogues and communal buildings were expropriated by the Soviets and transformed into sports centers or local museums. As for those that survived the early decades of Soviet rule, they were blown up by the Nazi German rulers during World War II. Some of the earlier stone synagogues survived in various states of ruin in Husyatyn, Sataniv, Sharhorod, Sokal, and Zhovkva. Uman's seventeenth-century Great Synagogue was — and still is — part of a tractor garage, Berdychiv's eighteenth-century Choral Synagogue became a glove factory, the Brodsky synagogue in Odessa a state archive, and the Uzhhorod synagogue a home to the local Philharmonic Society.

Painting and sculpture

Painting in Ukrainian lands can be dated to the seventh century BCE, when Greek colonies were established along the northern shores of the Black Sea and when the Scythian nomadic-pastoralists came to control the steppe hinterland. At the time, paintings served a decorative function on vases and pottery, which was either imported from classical and Hellenistic Greece or produced by artisans working in Chersonesus and other Greco-Roman northern Black Sea cities, including those within the sphere of the Bosporan Kingdom along the eastern shores of Crimea. Floor mosaics and mural paintings depicting ancient Greek gods and scenes of plant and animal life adorned domestic and public dwellings as well as the underground chambers of tombs unearthed in Crimea and the adjacent southern Ukrainian steppelands.

Mosaics, frescoes, and icons

The introduction of Eastern Christianity to Kievan Rus' in the late tenth century provided a new stimulus to painting, which became a major component of art in service to religion. The interior walls of the masonry churches were covered with mosaics and frescoes depicting Christ, the Apostles, the Virgin Mary, Old Testament prophets, and Christian saints. On occasion, as in Kyiv's monumental St Sophia Cathedral, some frescoes depicted secular subjects, such as hunting scenes, court entertainers (musicians, acrobats, and dancers), and church benefactors (in St Sophia's case, Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and his family).

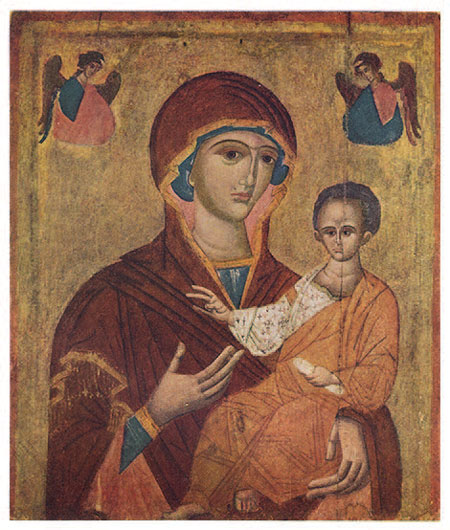

By far the most widespread form of painting in the service of religion was the icon. These "written" images, most commonly of Mary "the Mother of God" and of Christ, became in and of themselves objects of veneration. An Eastern-rite Christian, when entering a church, is expected to approach the center, bow, cross him/herself, and pay homage by kissing the icon on the stand (tetrapod) before the iconostasis as the very first act of worship. The veneration of icons also takes place in family homes, where the eastern, "sacred" corners of the living room traditionally have one or more icons arrayed. In the past, guests who visited a home were expected to cross themselves and bow before the family icon, even before greeting the host.

The images "written" on icons seem initially strange to non-Eastern Christians because of their two-dimensional "flat" rendering of the human face and figure surrounded by an unadorned gold background. Creative artistic imagination, characteristic of Western religious art, is shunned by iconographers, who are expected to reproduce a standardized image of the sacred figure and to do so anonymously. Since the image is believed to represent a heavenly archetype, the icon itself becomes a kind of window between the earthly and temporal worlds. Eastern Christian theology teaches that icons reproduce archetypes of sacred figures from the celestial world, who manifest themselves to humans on the "window" surface of the icon. Three-dimensional images are expressly prohibited, while the golden background is symbolic of the holy aura that permanently surrounds saints. It is also believed that icons, especially those of Christ are archetypes "not made by hands." In other words, icon writers, whether individuals or groups who work in teams on different elements of the image, become merely the instruments through which the heavenly spirit makes possible, as if by some miracle, the appearance of the image.

In consideration of the theologically inspired rules that govern iconography, one might assume that all icons produced for Eastern-rite Christian churches from Greece and Serbia to Ukraine and Russia look very much the same. And to the uninitiated this might certainly seem to be the case. Since, however, icon makers have been producing works over a long period of time — from the early medieval period to the present — and throughout an extensive geographic area, it is inevitable that stylistic variations exist. Therefore, while it is difficult to speak of a typically Ukrainian style in icon painting, except in the sense of the geographic place of production, it is possible to discern different iconographic traditions, usually determined by the monastic workshops where they were made.

The earliest icons associated with medieval Kievan Rus' were either imported from Byzantium or produced in Kievan monastic workshops following Byzantine prototypes. In later centuries, iconographers in Ukraine, as elsewhere, diverged from the Byzantine model; the most distinctive of these artists were the Galician school of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Features from the Galician-Ukrainian environment are clearly evident in the Mother of God and Christ child from Krasiv, rendered as a type of ethnic Ukrainian peasant, or a sixteenth-century icon from Yabloniv, in which Christ is wearing a robe with folk embroidery.

Another variation has come to be described as the Carpathian icon, which refers to a body of work done for local churches not only in Ukraine (in particular southern Galicia and Transcarpathia) but also in neighboring regions within present-day Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland. The Carpathian icon from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is characterized by an increasingly realistic depiction of personages from contemporary life. This is especially the case in icons that depict the Last Judgment, in which the damned from various social strata or ethnic origin, among them Jews, are easily recognizable.

In central and eastern Ukraine, icons painted in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries took a more realistic turn. This most likely occurred under Renaissance and Baroque influences from western Europe that reached Ukraine through the prism of Poland. Whereas icons retained some traditional elements like the obligatory gilded background, facial features were likely to be depicted in a more realistic manner. Moreover, alongside the holy image in the center there may be contemporary public figures, in particular officers connected with the administration of the Cossack state. Examples of such realism include a seventeenth-century Crucifixion with a portrait of the icon's donor (Cossack colonel Leontii Svichka) or the eighteenth-century St Mary the Protectress, who is flanked by Cossack Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi.

Secular painting

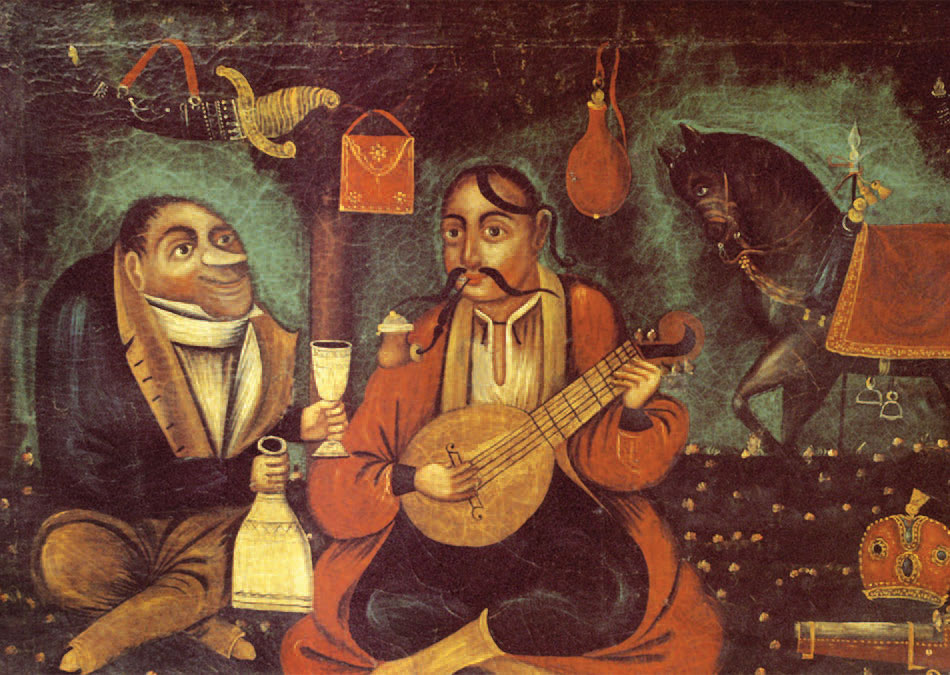

This same period, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, marks the appearance of an increasing number of paintings that were meant not for religious purposes (icons and frescoes) but rather for secular enjoyment. Taking their cue from Flemish and Dutch models, which were well known at the time in Poland-Lithuania and other parts of central Europe, painters in Ukraine responded to the wishes of their own Cossack state administrators and other civic figures to be immortalized through portraiture. The same Caves Monastery in Kyiv, which for centuries had served as the main center of icon production, now became home to several portrait painters.

The dominant style was Baroque, which in the hands of Ukraine's artists often resulted in portraits that were dark and somber. The only color might be in the embroidery of the clothing and in the family coats-of-arms in the top right corner, whose purpose was both to identify and enhance the social prestige of the subject. At a more popular level, and in a somewhat more rustic and naive style, was the tradition of folk painting, among whose most popular subjects were a legendary Cossack named Mamai as the figure of a Cossack minstrel, who sits cross-legged in a Buddha-like pose holding a musical instrument (kobza or bandura) played by plucking the strings. These secular figures were rendered over and over by numerous folk artists in a somewhat stylized manner that reminds one of the repetitiveness of icons.

As in previous periods, Ukraine's painters during the long nineteenth century were influenced by intellectual currents and artistic styles prevalent throughout the rest of Europe. The Romantic movement was a particularly important trend, with its recognition of the power of natural forces, including the irrationality of human nature, its fascination with remote places and events from the legendary past, and its emphasis on the creative genius of the individual artist. These characteristics were all present in the works of Taras Shevchenko (better known as the literary bard of Ukraine), whether in introspectively brooding self-portraits, in etchings depicting historic buildings and traditional life in a Ukrainian village, or in realistic images of suffering in the Russian imperial army which he experienced directly during ten years of punitive conscription.

Like religious art from earlier times, the secular art of the nineteenth century took on a functional purpose. This time the purpose was to elevate, even glorify, the Ukrainian nationality, with realistic scenes of present-day, rural life and depictions of real or imagined events from the historic past. Among the most notable painters, whose works still dominate the permanent collections in Ukraine's museums, are Serhii Vasylkivskyi, with his memorable scenes of Cossacks on the steppe, and Mykola Pymonenko, with his idyllic renderings of everyday village life. Rural landscapes, genre scenes, and portraiture remained a staple subject matter when, at the turn of the twentieth century, the Impressionist style from France reached Ukrainian lands, where it found expression in the works of Mykola Burachek, Oleksander Murashko, and Petro Levchenko.

These and a whole host of other painters are best remembered for genre scenes, landscapes, and depictions of historic personages and events, which consciously or unconsciously were intended to inspire pride and self-respect among ethnic Ukrainians, who, at least in the Russian Empire, were not even recognized as a distinct nationality. It is from this period that derive the iconic portraits of the two greatest Ukrainian writers of the late nineteenth century, Lesya Ukrayinka (1900) and Ivan Franko (1903), both by Ivan Trush. Among the more blatant examples of paintings that glorify Ukraine's past are the large-scale realistic historicist canvases of Mykola Ivasyuk, the most memorable of which is the "Entrance of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi into Kyiv, 1649" (1912).

This same period is also known for the work of painters who, despite their Ukrainian roots and attention to Ukrainian themes, are generally classified as Russian artists. The most renowned of them is the Ukrainian-born Ilya Repin, whose joyful depiction of "Cossacks Writing a Letter to the Turkish Sultan" (1880–91) has become a kind of iconic symbol of Ukrainianness to the outside world. Others include two painters from Crimea: Ivan Aivazovsky of Armenian background, famous for his seascapes as well as ethnic Ukrainian rural genre scenes; and Arkhip Kuindzhi of Greek background, noted for his dark night-time landscape scenes of the Crimean coast and Ukrainian steppe.

Modernism in Ukrainian art was, as in other parts of Europe, expressed in diverse ways. It could be a rejection of "ethnographic" Realism and refined Impressionism, with a preference for a more powerful and dynamic use of color and form, as in the Expressionistic portraits of Oleksa Novakivskyi. It could be a new school of fresco painting that rendered human forms in a neo-Byzantine or pre-Renaissance style, with figures often monumental in size and statuesque in pose, as in the work of Mykhailo Boichuk and his followers, the Boichukisty, who were later described as the School of Monumentalists. It could be the dynamic use of color in the style of French Fauvism as practiced by painters in Odessa's Society of Independent Artists (many of whom were Jews). Or it could be a complete rejection of figurative art in favor of a play with abstract forms and color. There was certainly nothing recognizably Ukrainian in such abstract works, other than that their creators may have worked in Ukraine and been inspired by its landscapes or, more often, cityscapes.

Influenced by the Cubist and Futurist movements in pre-World War I western Europe, painters in the waning years of the Russian Empire developed their own variant of abstract art known as Cubo-Futurism (a combination of French Cubism and Italian Futurism), with the creators of Suprematism (Kazimir Malevich) and Constructivism (Vladimir Tatlin) coming from Ukraine. These and other artists (David and Vladimir Burlyuk, Alexandra Exter, Mikhail Larionov, Oleksandr Bohomazov, Anatolii Petrytskyi), who are often described as leading Russian modernists, helped to transform Kyiv into a major center of the European avant-garde during World War I and the early 1920s.

During the interwar years, modernist trends were continued by artists in western Ukrainian lands that were not part of the Soviet Union. These artists included Oleksa Novakivskyi, Ivan Trush, and Modest Sosenko in interwar Polish-ruled Galicia, especially Lviv, and the so-called School of Subcarpathian Painting (Adalbert Erdeli, Yosyp Bokshai, Fedir Manailo) in Czechoslovak-ruled Transcarpathia, all of whom continued to have free reign to create in the styles that most fitted their personal tastes.

Meanwhile, in Soviet Ukraine, the state was about to impose restrictions on artistic creativity. Several modernists, now considered ideologically unacceptable, were imprisoned in the Soviet gulag; some chose exile in central and western Europe; others remained but adapted to the official guidelines known as socialist realism. Formally introduced in 1933, the ideology of socialist realism condemned abstract forms and expected painters to create figurative art, preferably in the nineteenth-century realistic style. In particular, artists were expected to choose subject matter that would inspire the working classes to even greater achievements in industrial and agricultural production under the leadership of wise Communist statesmen inevitably depicted in statuesque and often saccharine emotional poses as benevolent heroes of the new Soviet society.

The very titles of such paintings, all unveiled in the late 1940s and early 1950s, revealed their ideological purpose: praise for productive work ("The Queen of Socialist Labor Yevheniya Dolynyuk" or "Bread"); deification of Communist party leaders ("Stalin" or "Chairman Khrushchev Salutes a Cosmonaut"); political indoctrination among workers and youth ("Lenin Speaking with the Donbas Miners" or "Enrollment into the Communist Youth Movement — Komsomol"); and tributes to Russia, Ukraine's "elder" brother ("Forever with Moscow"). History, too, could be a source of inspiration, although in paintings intended for the Soviet Ukrainian public "bourgeois nationalist" heroes and events were now replaced by scenes that gave prominence to the masses in their alleged age-old struggle against feudal oppressors. Subjects were drawn from the far distant and more recent past, the best examples of which were large-scale canvases inspired with Baroque-like dynamism and force, such as Mykola Samokysh's "The Battle of [the Cossack] Maksym Kryvonos against [the Polish Aristocrat] Jeremy Wiśniowecki" (1934) and "The Red Army Crosses the Sivash Sea [to Liberate Crimea]" (1935) or Fedir Krychevskyi's "Victors over [the White Army General] Wrangel" (1930).

Alongside officially sanctioned socialist-realist painters were non-conformists who, due to the modernist style they employed, did not receive approval from the Soviet authorities. The non-conformists may have been marginalized and restricted from exhibiting their works in public, but they nonetheless continued from the 1970s to create in a wide body of work in avant-garde styles (Feodosii Humenyuk, Volodymyr Makarenko, Ivan Marchuk, among others), some of which made use of colorful folk-inspired decorative designs (Mariya Prymachenko, Hanna Sobachka-Shostak, and Kateryna Bilokur). Their works were to have an impact on subsequent generations of creative artists who were able to work in a more politically relaxed environment. In the waning years of the Soviet Union and in post-Communist independent Ukraine, when the restrictive guidelines of socialist realism have been lifted, Ukraine's painters have worked in a wide range of styles that may be figurative, abstract, or a combination of both.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.