Chapter 8.3: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 8.3

Sculpture

Sculpture has an extremely long tradition in Ukrainian lands, with artifacts uncovered by archeologists that date back to pre-historic times. The most widespread finds are small-scale terra-cotta stylized figures of humans and animals produced during the period of Trypillian culture throughout much of central and southwestern Ukraine between 4500 and 2200 BCE. Subsequently, the high level of culture that existed in southern Ukraine, in particular along the Black Sea and in Crimea, is reflected in remnants of free-standing and relief figures of ancient Greek gods (from the third to second centuries BCE) and exquisite small-scale ritual objects and jewelry carvings in gold connected with the Scythians (fourth century BCE).

After the Christianization of Kievan Rus' in the late tenth century, the Eastern-rite Church was generally opposed to free-standing human sculpted figures, since they were reminiscent of the pagan idols that the new Christian religion set out to destroy. Consequently, "religious" sculpture was limited to stone-carving reliefs on church portals, column capitals, and sarcophagi and to carved embellishments, usually in wood, on icon screens (iconostases) that dominated Eastern-rite church interiors. This meant that, for much of the medieval and early modern periods, sculptural depictions of the human form developed mainly among those peoples and cultures in Ukraine that were not connected with Eastern Christianity. These included Polovtsian and other nomadic Turkic tribal groups who left behind in the steppelands that they dominated between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries so-called stone babas. The babas are bulky, mostly female figures (three to twelve feet, or one to four meters, high) in either standing or sitting positions, which were commonly used as grave markers.

Even more evident in Ukraine's public space were the sophisticated renderings of human forms (usually saints and other religious figures) carried out by sculptors in the Italianate Renaissance and Baroque styles for Roman Catholic churches and cemeteries that were built in large numbers, especially in western and central Ukraine, during the sixteenth-to eighteenth-century period of Polish-Lithuanian rule. The most accomplished of these sculptors was Johann Pinzel, who in mid-eighteenth-century Galicia created full-length statues of saints for the Rococo façade of the Eastern-rite St George Greek Catholic Cathedral Church in Lviv and side-altar wooden figures for the Roman Catholic church in Monastyryska.

Aside from sculptural work connected with Catholic churches in western Ukraine, rural carvers continued to produce throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries — for both Western-and Eastern-Rite Christian communities — wayside crosses that can still be seen at the two ends of most villages, especially in the western part of the country. At the same time, professional urban-based sculptors created in wood and bronze small-scale works for financially well-to-do patrons who wished to enrich through art their personal residences or, in some cases, their art galleries. It was, therefore, not in a vacuum that arose two of the twentieth century's most innovative sculptors, Alexander Archipenko and Vladimir Tatlin, even though both worked primarily abroad and left little of their creative work in their native Ukraine.

It is large-scale sculptural works that are best known to the public-at-large, and it is these kind of monuments that often define Ukraine's cultural landscape, especially in squares, parks, and government building complexes in the country's urban areas. Most of what one sees today are works that date from the nineteenth, twentieth, and first decade of the twenty-first century. In almost all cases, the public sculptural projects were commissioned by some level of the ruling government or by a local civic body: in other words, sculpture in the service of the state and/or of the nation.

Not unexpectedly, the subjects of such commemorative sculpture have invariably been figures of historical significance (rulers, statesmen, military figures, cultural and religious leaders) or symbolic depictions connected with a specific event. Of course, what one calls historical significance is determined by the ruling regime at the time a given work is commissioned. Since heroes and glorious events for one regime may be enemies and tragedies for the regime that follows, it is not uncommon in Ukraine — as elsewhere — for monumental sculptures to outlive their usefulness and be dismantled and replaced by something that is acceptable to the political ideology of the moment.

What remains in Ukraine from the long nineteenth century are works that represent political or religious phenomena common to all East Slavs, in particular Russians and Ukrainians. Two monumental statues in Kyiv, of St Volodymyr/Vladimir (1850–53) overlooking the Dnieper River and Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (1888) ostensibly pointing in loyalty toward Moscow, are the best examples from this period. On the other hand, the numerous statues of tsars and their officials (with the exception of military figures) from the former Russian Empire, and of Polish, Romanian, Hungarian, and Czechoslovak kings and statesmen from previous regimes in western Ukraine, were politically unacceptable to the new Soviet authorities and, therefore, dismantled and destroyed. Among the few exceptions is the monument to the Polish national bard, Adam Mickiewicz, which was left alone and remains in the main square of Lviv where it was erected in 1904.

During the period of Soviet rule — after 1920 in eastern Ukraine and after 1945 in western Ukraine — thousands of statues were erected (sometimes in the same places where once stood figures from the "feudal" past) to the heroes of the new regime: Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx, Joseph Stalin, and the modern revolutionary class-conscious Russian writer, Maksim Gorky. These and other statues of revolutionary figures (Bolshevik activists, Red Army generals and soldiers, outstanding industrial and agricultural workers) and a select pantheon of ideologically "progressive" cultural figures from the past (most especially the Ukrainian national bard Taras Shevchenko) were rendered according to state-approved socialist-realist guidelines. In practice, this most often resulted in pompous, larger-than-life figures that were remarkably similar in style to the "totalitarian" sculpture produced in fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, and later Communist China. The striving for grandiosity reached its peak with the 102-meter-high monument to World War II, called simply "Motherland" (1981), set in the hills of Kyiv overlooking the Dnieper River.

The last two decades since Ukraine became an independent state have witnessed an ongoing cultural battle among conflicting forces intent on appropriating public space for their respective ideological needs. Monuments featuring sculpture are in the forefront of these struggles; many (but not all) statues of Lenin have been dismantled (Stalin statues had already for political reasons disappeared in the late 1950s and 1960s), while statues of some figures from the pre-revolutionary tsarist past have been restored (most notably Empress Catherine II in Odessa, 2007, and her favorite minister, Gregory Potemkin, in Kherson, 2003).

Very often the places that had been allotted to Lenin are filled with new statues to Taras Shevchenko, while figures who were ignored or banned outright by the Soviet regime are now the subjects of statues that have redefined a whole host of squares and parks. These include rulers from medieval Kievan Rus' — St Olga in Kyiv (1996), Yaroslav the Wise in Bila Tserkva (1983), and Danylo of Galicia in Halych (1998) and Lviv (2001); the sixteenth-century slave turned first lady of the Ottoman Empire, Roksolana, in Rohatyn (1999); the seventeenth-century Cossack defender of Ukraine, Petro Sahaidachnyi, in Kyiv (2001); the favorably remembered (in western Ukraine) nineteenth-century Austrian Habsburg emperor, Franz Joseph, in Chernivtsi (2006); and several figures from the twentieth century––the historian and Ukraine's first president, Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, in Kyiv (1998); the respected Greek Catholic archbishop, Andrei Sheptytskyi, and his brother Klymetii, in Prylbychi (2011); the "national Communist" Mykola Skrypnyk in Kharkiv (1969); and the controversial anti-Soviet nationalist leader Stepan Bandera in Drohobych (2004). Ukrainians of Jewish descent have also become part of the country's public urban space with recent statues of the poet Paul Celan in Chernivtsi (1992); the popular jazz singer Leonid Utesov/Lazar Vaisbein and writer Isaac Babel in Odessa (2000 and 2008 respectively); and the writer Sholem Aleichem and actor Zinovii Gerdt in Kyiv (1997 and 1998 respectively).

The question about who is deserving of a statuary monument, whether in the form of an individual figure or group of figures, has at times prompted heated public debate, which, for example, surrounded the rededication of the Odessa monument to Empress Catherine II (opposed by Ukrainian patriotic elements) and the construction of several new monuments in western Ukraine in honor of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and its exiled leader, Stepan Bandera, in Lviv (2008), and its military head, Roman Shukhevych, in Tyshkivtsi (2012) (opposed by war veterans and others sympathetic to the Soviet past). Controversy has also surrounded and delayed the construction of monuments associated with some of Ukraine's minority peoples, such as one commemorating the late-ninth-century crossing of the Carpathians by Magyars/Hungarians (opposed by Ukrainian nationalists from Galicia) and several non-figurative memorials commemorating the forced deportation of the Crimean Tatars in May 1944 (opposed by Russian nationalists in Crimea). Less controversial, except perhaps on aesthetic grounds, are several monuments, some with figurative statues, memorializing the Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1933, the destruction of Jewish communities during the Holocaust, and the victims of Communist rule.

Jewish traditional art

Jewish tradition from antiquity forbids creating images that can be used as objects of worship, but it endorses images used as the references to, or the attributes of, the divine. Therefore, most of the wooden synagogues in Ukraine — good examples of which are at Hvizdets, Khodoriv, Mikhalpol, and Smotrych — were exuberantly painted inside and out by Jewish folk artists. Only a few names of these Jewish synagogue painters are known; one is Mordekhai Lisnitsky. The paintings consisted of floral ornaments with redemptive messages often associated with the tsemakh, alluding to the biblical tsemakh David (the offspring of King David), the long-awaited redeemer-to-come. Synagogue ceilings displayed the signs of the Zodiac, endorsed for two millennia as a legitimate symbol in places of Jewish worship, and quite often there were ornamental fauna as elements of traditional Jewish symbolism on menorahs and columns.

All elements of traditional Jewish art found in synagogues, including the carved wooden or stone sculptures adorning the Holy Ark (Heb.: aron ha-ko-desh; Yid.: oren ha-koydesh), the curtain covering it (parokhet), and the fauna and flora ornaments on the ceiling and walls, were intended to be read, understood, explained, and interpreted. They formed a visual continuation of the traditional commentary on classical texts and parts of the liturgy. In a real sense, they were a graphic extension of Jewish oral culture. The bimah, or elevated podium with a table on which the Torah scroll was read on the Sabbath and on festival days, was covered by a bridal canopy, suggesting at the moment of the Torah reading the loving union between the Jewish people as the bride and God Almighty as the groom.

There were some common decorative elements that appeared with only stylistic variation in the interiors of most synagogues. The two pillars of the Holy Ark symbolized the two pillars of Jerusalem's Second Temple destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. The two lions represented the tribe of Judah, which supported the pillars of the imaginary Jerusalem Temple; consequently, synagogues were called in Judaic tradition mikdash meat, the little temple. A unicorn associated with Joseph and a lion associated with Judah, when depicted together, referred to the final redemption when these two messianic figures in Judaism (one, the son of Joseph, the other, the son of Judah) would meet. Flowers growing out of one another were another symbol of redemption, which was — and is — as imminent as the growth of creeping plants. A deer (tsvi in Hebrew) stood for the land of the deer (erets tsvi), a biblical metaphor for the Holy Land, while eagles referred to the biblical verse "[I will carry you] on the wings of eagles." The meaning of all these direct and oblique references was clear to every traditional Jew. Hence, when entering the synagogue, one went on an imaginary pilgrimage to the Almighty's dwelling-place in the Holy City of Jerusalem. From a synagogue somewhere in Ukraine, communal worship transferred a Jew on the wings of eagles to the Holy Land, known in Yiddish as eretz Yisroel.

Folk paintings typically adorned Jewish homes. Known as Mizrakh and Shiviti, they depicted, along with other symbols, Psalm 67 (known as the Menorah psalm) in the form of a seven-branch candelabra. They were placed on the eastern wall of the home to mark the direction of daily prayer toward the east, that is, toward Jerusalem. These popular folk paintings were usually of painted paper cut-outs which symbolized the Holy Land, the restored Temple, and the final redemption.

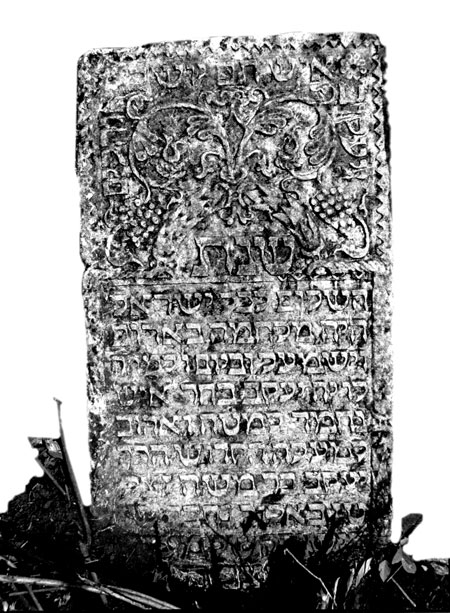

Symbolism was also present in a unique form of Jewish traditional art: tombstones (Heb.: matsevot; Yid.: matseves). Usually hewn from limestone by professional Jewish carvers, the tombstones contained not only epitaphs but also sophisticated ornaments, such as the hands of the priests (kohanim) spread in blessing, the hands of Levites with a jar washing the hands of priests, a lion (if the person was named Leyb) or a wolf (if the person's name was Zeev), and exuberant floral ornaments as well as deer and eagles symbolizing the Land of Israel. If a person was unable to get to the Holy Land, in the Jewish popular imagination he or she would be transferred there after death by the symbols at the gravesite. Great rabbis and Torah scholars merited a crown on their graves, symbolic of their status as teachers of Judaism, which exemplified the highest level of human knowledge. Tombstones dating from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries became a significant part of the Ukrainian cultural landscape. Among the more unique examples are in Jewish cemeteries in Belz, Berdychiv, Kosiv, Medzhybizh, Sadhora, Shepetivka, and Zhynkiv, many of which have appeared as part of the scenery in Jewish films and plays, as the subject of Jewish poetry and prose, or in the works of leading eastern European avant-garde painters.

Jewish secular painting

The first modern artists of Jewish descent in Ukraine appeared in the wake of the Reform Era (1860s) in the Russian Empire. As a result of the reforms initiated during the reign of Tsar Alexander II (1855– 81), Jews were given access to higher education and the promise of greater social mobility and cultural integration. Many gifted Jews found their way to art schools in St Petersburg, Moscow, Kyiv, and Odessa. Among the first was Abraham Manievych (Abram Manevich), a native of Belarus who studied and taught in Kyiv. Influenced by French Impressionism, Manievych created dozens of Ukrainian landscapes, some of which ("Spring in Kurenivka," 1913), had recognizably Jewish overtones. Another painter influenced by late-nineteenth-century modernist trends from western Europe was Natan Altman, a native of Odessa and graduate of the Odessa School of the Arts, who subsequently became renown as a designer of theatrical and stage sets.

In the decade before the outbreak of World War I, Ukraine, in particular Kyiv, became one of the major centers of twentieth-century artistic trends, including Futurism, Cubism, Art Nouveau, and an amalgam of the avant-garde. Among the artists who established studios and salons in Kyiv and had a significant impact on the city's cultural life was Alexandra Exter (née Grigorovich) from the Polish-Belarusan border town of Białystok. This was also a time when several European painters started careers in their native Ukraine before leaving permanently for Germany, France, the United States, or Israel. Because of Ukraine's stateless and little-known status, these figures came to be known as "Russian-Jewish" or "Russian-French" artists. Among them was Sonia Delaunay (b. Sara Stern) from the Katerynoslav region, who settled in France; Borys Aronson, who began with the Kyiv-based Kultur-Lige and ended up as an extremely productive American theatrical artist (most famous for the scenery in the movie Fiddler on the Roof), and Joseph Zaritsky, who continued the innovative coloristic endeavours of Matisse and Cézanne while still in Ukraine, until he moved to the British Mandate of Palestine where he became one of Israel's most important painters.

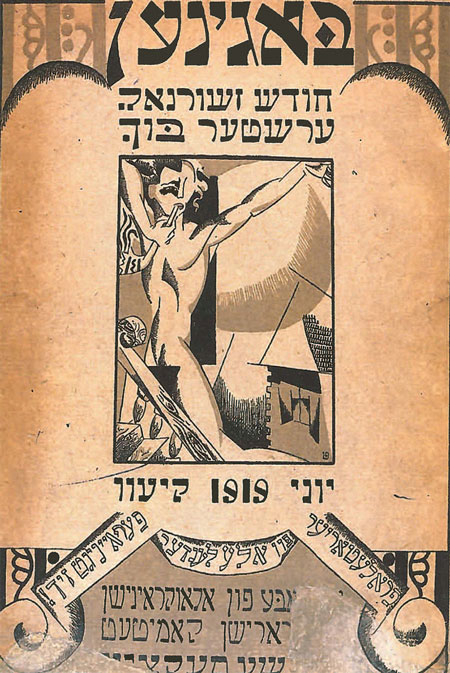

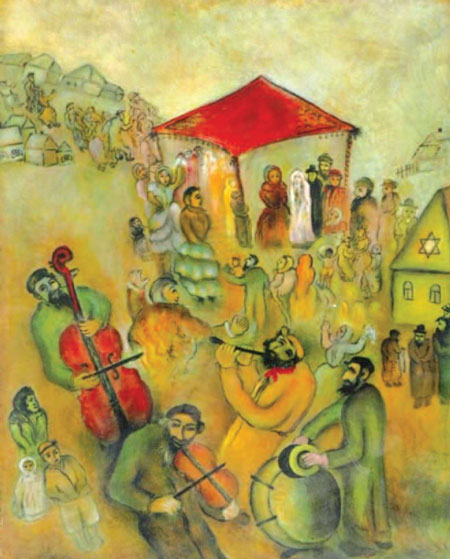

Aside from its role in theatrical life, the pre-World War I Kultur-Lige (or Yiddish Culture Society) included among its ranks an artistic group that continued to function during the period of Ukraine's independence (1917–1920). The Kultur-Lige avant-garde artists identified with the anonymous Jewish folk painters of the distant past who carved tombstones and decorated synagogues. Like their predecessors who created folk items for ritual use, the new revolutionary artists also felt committed to serve their people — but with a different goal. That new goal was best displayed in Iosif Chaikov's cover design for the journal Baginen (Dawn), which cast traditional Judaic symbolism in a revolutionary mold. Chaikov portrayed a naked newborn Adam, a person of the new age without any ethnic features, an everyman who lifts the ram's horn to trumpet the birth of the new world as in the synagogue during the Jewish New Year (rosh ha-shanah). This creative usage of old Jewish symbols was done in the service of a revolutionary, boundary-crossing, avant-garde art.

Among the plethora of outstanding artists who helped launch the Kultur-Lige program of cultural revolution through art and education were Alexander Tyshler, Iosif Chaikov, Mark Epstein, and Issakhar Ber Rybak. Experiments with form did not prevent them from creating ethnographically precise and historically relevant images based on their native Ukrainian environment. Rybak, for example, produced several albums of etchings inspired by Ukraine's Jewish world: "The Shtetl" (1923), "The Pogrom" (1918), and "Jewish Images in Ukraine" (1924). Another painter, Mane-Kats (Emmanuel Katz) from Kremenchuk, drawing heavily on the artistic experiments of his Ukrainian and Jewish contemporaries, was perhaps the first avant-garde painter to create artistic images of the shtetl. All these Jewish artists worked side by side with the creators of revolutionary trends in Ukrainian art, such as Alexander Archipenko, Mykhailo Boychuk, and David Burlyuk. In addition to teaching art to the Yiddish-speaking masses and designing dozens of posters and book jackets, Ukraine's Jewish artists connected with the Kultur-Lige painted workers' dormitories, designed logos for military armoured trains, and created scenery for Yiddish theatrical stages. By the early 1930s, following the Soviet government's implementation of socialist realism as the guiding principle for artistic creativity, avant-garde techniques were scorned and traditional imagery considered obsolete. Some Jewish artists from Ukraine did, however, create in a realist style that soon became the norm in the Soviet art world. Aron Futerman, from a village near Korosten, designed dozens of monuments to revolutionary leaders, while Isaac Brodsky from Sofiyivka created a highly romanticized version of socialist realism, with portraits of Lenin and other Soviet leaders as well as epic paintings, such as "Execution of the 26 Baku Commissars" (1925). It was works such as these that laid the foundation of visual Soviet propaganda and official mass culture, although in the case of Brodsky the results were at least of high artistic quality.

Jewish artists and scholars from other parts of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union were also drawn to Ukraine. In the 1920s the Leningrad painter Solomon Iudovin was creating poignant and apocalyptic images of the shtetl. They were based on impressions of Ukraine's Jews that he acquired during a trip taken earlier in the century with the ethnographer S. An-sky through the central provinces of the Pale (mostly Volhynia and Podolia). Iudovin's trip inspired his later etchings, which today are considered a quintessential portrayal of the traditional Ukrainian shtetl and its synagogues.

By the late 1930s, however, Jewish themes in Soviet art had almost disappeared unless they were connected to the celebration of Jewish proletarians and peasants. Following the closure of Yiddish-language schools and theaters in the 1940s, Jewish artists transformed themselves into innocuous illustrators of children's books for the Soviet public at large. Together with dozens of Jews who became children's writers and poets, they helped create a popular corpus of twentieth-century children's literature that was untouched by ideological concerns. Nonetheless, these artists did not escape the anti-Jewish persecutions that characterized the period after World War II. Zinovii Tolkatchev became the object of attack for his albums of Holocaust-based illustrations such as "Maidanek" and "The Flowers of Oswięncym." Why? The Soviet authorities accused him of bourgeois nationalism for emphasizing the exclusiveness of Jewish suffering during World War II.

In the 1960s, during the short-lived political Thaw, several artists of Jewish descent enriched Soviet Ukrainian artistic circles. David Miretsky was inspired by the country's leading socialist-realist painter, Tetyana Yablonska, to create colorful representations of the homo sovieticus. This idealized Soviet person, with characteristics of the unsophisticated lumpenproletariat, seemed to be a figure with recognizable Jewish features. With his deep empathy toward ordinary people, Miretsky crafted — in the style of Breughel — ragicomic Soviet people going about their daily lives, whether shopping at a butcher shop or bakery, playing dominoes in a courtyard, or taking a walk on city streets. Mikhail Turovsky, like Miretsky from Kyiv and also a disciple of Tetyana Yablonska, became a productive book illustrator and portraitist. His often bright Matisse-inspired nudes defied Communist party officials who otherwise had forbade him from exhibiting most of his best works. Borys Lekar from Kharkiv, whose his career as an architect is best remembered for the design of the boulevard near Kyiv's St Sophia Cathedral, later became a watercolorist and painter. His portraits of famous composers and writers sought to transcend human materiality and physicality by rendering the human face as a stream of emanating light. Although a native of Soviet Central Asia, the prolific Akim Levich created series of works depicting traditional towns and shtetls in Ukraine as seen through fading memories and creative nostalgia. Not being able to exhibit their best work and often left without the means of existence, all these artists (except Levich) emigrated to the West in the 1970s and 1980s.

After Ukraine's independence, new painters of Jewish background openly declared their desire to reconnect with the artistic and religious tradition from which they and their predecessors had been forcefully separated. Thus, the painter Alexander Roitbrud turned to post-modern themes, creating images that depict the collapse of the Soviet universe. Matvei Vaisberg practiced what he called the "artistic rearguard," that is, figurative and thematically based art that combined eastern European iconography with elements of folk art and of biblical and modern-day Israeli themes (as in the series titled "Judea Desert" and "Seven Days"). Vaisberg's monotypes and canvases often display shades of gold as a reminder of the lost grandeur of traditional Jewish imagery and sacred art.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.