Chapter 9.1: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 9.1

Music

Folk music

Ukrainian folk music

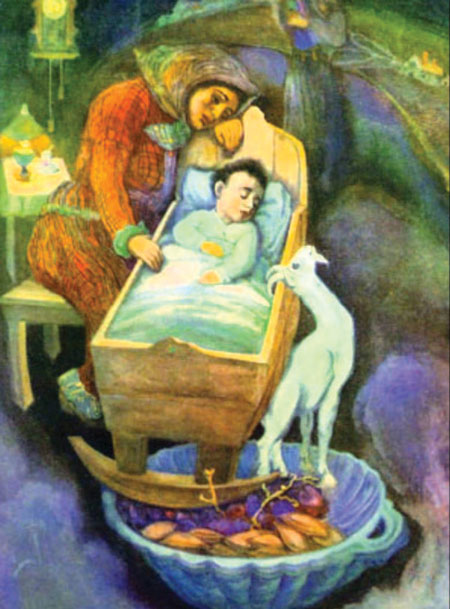

Musical folklore is part of a people's collective memory manifested in singing, instrumental music, and dance that is associated with oral traditions transferred from generation to generation. Ukrainian musical folklore is very old: there are references to song performers in medieval eastern European chronicles, while sixteenth-century diplomats mention them as ubiquitous and respected figures at ruling courts. Songs with a plethora of subgenres were — and still are — the most characteristic feature of Ukrainian culture and tradition. It is no coincidence that many Jewish enthusiasts of Ukrainian culture fell in love with Ukraine and its language because of the songs they heard in their childhood. For an ethnic Ukrainian child, knowledge of language, customs, music, verse, and rhythm begins with kolyskovi (lullabies) and zabavlyanky (fun songs). The child's early exposure to folklore includes music with a predominance of minor scales and with lyrics that are sad and at times filled with frightening images. Such music had a ritualistic protective function, keeping evil away from the child.

Ethnic Ukrainians created a wide range of songs to accompany practically every national, communal, family, and intimate event in their lives. Among such ritual songs are vesnyanky (to greet the beginning of spring), hayivky (to welcome the blossoming of forest vegetation), kolyadky (Christmas carols), shchedrivky (New Year's Eve carols), and ryndzivky (greeting songs for married and unmarried women at the beginning of the New Year, usually performed in Galicia). Humorous songs, such as the older kolomyiky in western Ukraine or, from Soviet times, chastivky in eastern Ukraine, are intended to mock selfishness, greed, gluttony, lust, drunkenness, and other human foibles.

Ukrainian musical folklore combines folk and Christian elements, with the result that it retains ancient pre-Christian pagan references, images, and beliefs. For example, vesnyanky (spring songs), kupalski (Ivan Kupala fortune-telling, erotic, and lyric songs), and zaklychky (invocating songs) hark back to pagan beliefs connected to the sacral meaning of seasonal change, the choice of a life partner, and the animistic nature (possessing a soul) of plants, trees, and crops. Similarly, tsarynni songs, which are associated with fence-building to protect arable lands, emphasize the pre-Christian prejudice that crows bring bad luck. All these songs were subsequently adapted to various holidays of the Christian calendar.

Songs came to play such a crucial role in national self-identification that ethnic Ukrainians created a humoristic and inoffensive image of a Cossack who reacts by singing an extemporaneously composed song about anything that happens to him. In a well-known eighteenth-century Ukrainian joke, a Cossack riding with his brethren on a wagon catches his foot between the spokes of the wheel: "Oy, my foot…," he exclaims, prompting the entire group immediately to burst into a refrain on the words: "Oy, my foot…"

Ukrainian musical folklore includes a wide variety of genres centered primarily around males. Aside from Cossacks are the chumaky (ox-cart drivers known for transporting salt from Crimea), recruits conscripted for service in the tsarist army, and peasants, whose songs accompanied planting, sowing, shepherding, and harvesting. Genres of musical folklore that emerged from life-cycle events include vesilni (wedding songs) and zhurni (mourning dirges), both of which are usually performed by groups of females. The music is generally characterized by minor/major alternation-built polyphony around the fifth, third, and octave intervals.

Because of their association with the early modern Ukrainian state and nationhood, Cossack songs are by far the most beloved and popular among ethnic Ukrainians. Although narrating earlier events, most extant Cossack songs reflect eighteenth-century sensibilities. They glorify the seventeenth-century Cossack uprisings and eighteenth-century haidamaky (peasant rebels), all the while bemoaning the sufferings of Cossack leaders captured and tortured by enemies and lamenting their waning military might. The various genres among these songs include dumy (lyrical epic songs) and psalmy (biblical and quasi-biblical glorifications). Quite sophisticated in form, Cossack songs used both cantilena (singing) and recitative narration song to diatonic melodies in alternating major/minor scales.

Cossack songs were traditionally performed by vagabond kobzari and lirnyky, named for the instruments they played, on the kobza (a stringed instrument in the lute family) and the lira (a hurdygurdy). Hundreds of listeners would gather around them during annual fairs or on market days in order to listen to performances that in a sense continued the oral epic tradition from medieval times. The kobzari and lirnyky appealed to the imagination of listeners, helping them identify with and rejoice in their common glorious historical past. The importance of these kinds of public performances in ethnic Ukrainian cultural life manifested itself not only in the title of Taras Shevchenko's most famous literary work (Kobzar), but also in visual folk art epitomized in the exceedingly widespread image of the Cossack Mamai, performing on his kobza and surrounded by attributes of Cossack military life.

Ethnic Ukrainian folklore developed through intensive interaction with the traditions of surrounding peoples. In the northwestern part of Ukraine (Polissia), one finds musical scales similar to those of Belarusans and Russians, while the Cossack folklore of southeastern Ukraine has absorbed a fair amount of Crimean Tatar and Turkish elements. On the other hand, in far western Galicia (including the Lemko region) and Bukovina, vocal as well as dance music is influenced by Slovak, Hungarian, Romanian, and Romany/Gypsy motifs and rhythmic patterns.

Throughout Ukraine major life-cycle events, in particular weddings, are celebrated with singing and dancing accompanied by musical instruments. Ukrainian folk bands traditionally consisted of three musicians who, depending on the situation, geographical area, and purpose, used a variety of instruments, including the sopilka or floyara (a type of flute), the tsymbaly or dulcimer (a wire-stringed instrument played with light hammers), the bandura (a plucked-stringed instrument) and its predecessor, the kobza, the drymba (a small reverberating metallic piece), the tambor and tulumbas (drums of different sizes), the basolya (a kind of folk cello), and the serbyn (a type of fiddle). Some of these instruments were foreign in origin (Balkan, Turkish, Italian, Polish) but adapted for local purposes; others were indigenous to Ukraine's vast territory from the Carpathians to the Kuban steppes, reflecting local lifestyles and traditions deeply rooted in rural life. Dance as a folkloric tradition also had both local and foreign roots. Aside from dances indigeneous to Ukraine — the arkan, hopak, kolomyika, kozachok, and metelytsya — others that were widespread included the polka and krakovyak of Moravian and Polish origin and the quadrille of western European aristocratic provenance.

Aside from instrumental music and dancing at social occasions, baptisms, weddings, funerals, and other life-cycle celebrations included vocal music by groups of singers, usually female. The popularity of group singing was reinforced by Christian church tradition (that of all denominations common to Ukraine), which encouraged participation in the liturgy in the form of an exchange between the cantor and the congregation. By the nineteenth century, choral performance of folk songs became a central part of the Ukrainian musical scene and an important component of cultural continuity for pre-revolutionary, Soviet, and post-Soviet Ukraine. Choral tradition also found its way into highbrow literature (Vynnychenko wrote a play about "collective singing") and into urban folklore, which includes numerous jokes about ethnic Ukrainians who, despite being faced with life-threatening circumstances, somehow found time and energy to establish a choir.

Although during Soviet times public manifestations of traditional Ukrainian national pride were considered bourgeois-nationalist and subversive dangers, the authorities still encouraged a wide range of politically benign amateur and professional song ensembles at both the national (Virsky Ensemble, Ikonnyk Choir) and oblast levels. Nevertheless, several genres of Ukrainian songs were suppressed by the Soviet regime, in particular military songs and marches connected with the Ukrainian National Republic's troops (striletski songs) and songs of the nationalist guerilla units fighting during World War II (povstanski songs).

Under the impact of the bel canto singing tradition introduced through opera performances and new romantic attitudes toward folklore, nineteenth-century Ukrainian-language authors composed lyric verses, which at times became so popular they were believed to be actual folklore. Among the best known of these "literary folk songs" are Viktor Zabila's "Ne shchebechy, soloveiku" (Do Not Sing, My Nightingale), Mykhailo Petrenko's "Dyvlyus ya na nebo" (I Am Looking at the Sky), Kostyantyn Dumitrashko's "Chorni brovy, kari ochi" (Black Eyebrows, Hazel Eyes), and, the most famous of all, Mykhailo Starytskyi's "Nich taka misyachna" (The Night Is Full of Moonlight). Several of Shevchenko's poems, originally inspired by Ukrainian musical folklore, returned to their popular realm after being turned into songs. Other Ukrainian poems that became popular songs include Andrii Malyshko's "Ridna maty moya" (My Dear Mother) and Volodymyr Ivasyuk's "Chervona ruta" (Red Rue).

Ukrainian musical folklore has attracted arduous admirers among composers both within and beyond Ukraine, including Petr Tchaikovsky, Mykola Lysenko, Mykola Leontovych, and Béla Bartók, all of whom recorded and immortalized folk melodies in classical musical forms. Folk elements were also used liberally in the stage works (The Wedding in Malynivka, 1938, and Sorochyntsi Fair, 1936, among others) of Oleksii Ryabov, the Franz Lehár of Ukrainian operetta, a genre that was especially popular in Soviet Ukraine both before and after World War II. By the second half of the twentieth century, over forty popular musical groups and bands utilized folk music in their repertoire. A new generation of composers (Yevhen Stankovych, Leonid Hrabovskyi, Ivan Karabits, and others) continued the tradition of using elements of folk music of both rural and urban origin in their operas, cantatas, and symphonies. These traditions remain alive in Ukraine's contemporary musical scene, whether in "high" classical genres (Lesya Dychko and Oleksandr Shchetynskyi) or in popular rock music as dozens of groups garner mass support through their reliance on Ukrainian folk music. It was a galvanizing performance of the pop singer Ruslana (Ruslana Lyzhychko) based on Carpathian Hutsul folk motifs that won her first prize at the prestigious Eurovision — European Song Contest in 2004.

Jewish folk music

Music permeated the everyday life of ordinary Jews as much as it did the everyday life of ordinary ethnic Ukrainians. To begin with, Jewish men and women always chanted their daily prayers. The chants combined melodies and recitative lyrics in a form that was both canonized and individual. Children in elementary school and young boys in Talmudic academies also chanted the texts they studied, using what was called gemorenign (Talmudic spiritual melody). It had easily memorizable emphatic rising tones, question-tunes built on five-degree intervals, and a concluding cadence.

At the festive table on the Sabbath and holidays, Jews always sang songs, whether nigunim (spiritual melodies) or zmiros (religious songs), which were known and chanted by all. It is true that the Talmud contains strict prohibitions against adult men listening to a woman's voice (kol isha), which is believed to arouse uncontrollable sexual emotions. Nevertheless, until the rise of ultra-Orthodoxy, women did sing at the family table and in the synagogue together with men. The Talmudic prohibition did not apply to the mother-child relationship. Lullabies that Jewish mothers sang to their children were often the same ones sung by the peoples among whom the Jews lived. It is, therefore, not surprising that Ukrainian and Jewish lullabies used similar minor-key melodies, soft modulations, and sorrowful imagery.

Although the synagogue had its own cantor (Heb.: hazan; Yid.: hazn), who was a vocal master in great demand, practically every educated male Jew could, if necessary, lead prayers. This happened because, first of all, praying aloud was a communal practice and, second, because some basic prayers — such as those recited during the major holidays, new month celebrations, and the Sabbath — had more than one established melody from which any congregant could freely choose and reproduce.

The melodies varied from community to community and from shtetl to shtetl. It was also not uncommon for professional cantors to borrow from non-Jewish music, whether from folk songs in the early modern times, from the operatic and operetta repertoire in the nineteenth century, or from popular urban tunes in the twentieth century. Looking for solid income, many great cantors from Ukraine moved westward and accepted lucrative positions with larger congregations in Europe (Warsaw, Vienna, Berlin) and North America (New York City). For example, Gershon Sirota from Odessa performed in Vilnius and Warsaw, toured throughout Europe, and made high-quality vinyl-disk recordings, while Yossele Rosenblatt from Bila Tserkva, sometimes called the Jewish Caruso, toured Austria-Hungary and Germany before completing his hugely popular career in the United States as the star in a Hollywood movie about a jazz singer.

Traditional Orthodox Jewish liturgy — unlike the modernized Reform one — had (and has) no musical instruments, since Judaism like Eastern Christianity proscribes playing instruments on holy days. Instead, Jews sang. After all, the synagogue was a replica of the Temple in Jerusalem, where Levites sang hymns, Psalms, and religious songs. In the diaspora, a synagogue's entire congregation assumed the role of the singing Levites. Weekly Torah portions were also chanted, in which the reader (bal koyre) used special musical tropes (taamim) developed as early as the eighth and ninth centuries and since then employed, although with some variations, by both Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews. Chanting the Torah and the Haftarah portion from the Prophets constituted the central part of the bar mitzvah ceremony. Hence, mastery of Torah-chanting tunes and tropes became an integral component of a young Jewish boy's entry into adulthood.

Despite the absence of instrumental music in traditionalist synagogues, some multi-talented nineteenth-century cantors and even rabbis did play the violin to accompany recitation of the opening Sabbath prayers until the last three stanzas of the Lekha dodi, a Kabbalistic Sabbath introductory hymn. At that point, the moment the Sabbath had "arrived," they would put the instrument down. On the other hand, during festivities such as weddings and on holidays which had no Sabbath prohibitions (Hanukkah and Purim) as well as during the intermediary days of the spring Passover and autumn Sukkot, instrumental music was widely used.

Instrumental music was essential, because such festivities were a time for dancing. Jews danced in lines, in a circle, and in couple formations. In most cases for couple dancing, handkerchiefs were used to avoid touching the partner of the other sex. While Jewish and Ukrainian dances shared dozens of genuinely folkloric melodies, each people also had its own dances. Among ethnic Ukrainians, the best known were the kozachok, hopak, and kolomyika. For Jews there were several: the khosidl — a Hasidic spiritualized dance that transforms yihud (unity with the divine) and dveykus (cleaving to the mystical source) into a theatrical show; the freylekh — vivacious wedding dances alternating between doleful and joyous melodies; and the sher — a couple's dance with elements of well-expressed yet moderated eroticism. Jews, and for that matter ethnic Ukrainians as well, hired itinerant musicians, the klezmorim, to play at their festivities.

Instrumental music was essential, because such festivities were a time for dancing. Jews danced in lines, in a circle, and in couple formations. In most cases for couple dancing, handkerchiefs were used to avoid touching the partner of the other sex. While Jewish and Ukrainian dances shared dozens of genuinely folkloric melodies, each people also had its own dances. Among ethnic Ukrainians, the best known were the kozachok, hopak, and kolomyika. For Jews there were several: the khosidl — a Hasidic spiritualized dance that transforms yihud (unity with the divine) and dveykus (cleaving to the mystical source) into a theatrical show; the freylekh — vivacious wedding dances alternating between doleful and joyous melodies; and the sher — a couple's dance with elements of well-expressed yet moderated eroticism. Jews, and for that matter ethnic Ukrainians as well, hired itinerant musicians, the klezmorim, to play at their festivities.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Hasidic religious leaders encouraged the use of popular music, although they sought to transform its erotic and secular overtones into the spiritual and the mystical. Like the Kabbalist mystics in the Land of Israel and the Sabbatian sectarians in the Balkans before them, the Hasidim in Ukraine argued that music helped uplift routine religious practices and streamline the words of the prayers, allowing liturgical requests to reach their ultimate addressee more directly and easily. Because the Hasidim believed that everything in the material and spiritual world contained a divine spark and was pregnant with spirituality, this view applied as well to music. They had no problem borrowing Ukrainian (and other non-Jewish) melodies, which they quickly adapted for Jewish usage. Also like ethnic Ukrainians, when Jews wished to make a joyful melody into a sad one, they changed the key to minor by lowering the third tone in the scale. More often, they augmented the second in between the third and fourth degree of the scale, imitating the Phrygian (freygish) mode, which is popularly known as the Gypsy scale.

The sweetness of the melodies of the Hasidic tsadik were compared to the sweetness of the Land of Israel; in other words, by singing a melody one could transport oneself to the Holy Land. When gathered around the tsadik's table (tisch), those present adapted a plethora of folkloric melodies to mark through singing the sad departure of Shabbat on Saturday night as if it were the parting of a groom and bride. The highly influential eighteenth-century Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav preached that only a combination of singing a nign, teaching the Torah, and dancing can bring genuine joy. The very act of dancing and singing might soften the impact of the harsh (and quite often anti-Jewish) decrees of the government, or perhaps even annul divine verdicts.

Many songs ascribed to Rabbi Nachman incorporate melodies characteristic of the organ grinders and dulcimers (tsymbaly) of itinerant Ukrainian musicians. The religious leaders of the Belz, Boyan, Makarov, Ruzhin, and Vizhnitz Hasidic courts emphasized the importance of melodies, arguing that they helped individuals focus on the internal meaning of religious songs (zmiros) and thereby achieve the ecstatic moment of cleaving to the divine. It is also through the Hasidim that the Jewish music of Ukraine reached the Holy Land. A nineteenth-century emissary to the Jewish communities in Palestine reported that he had been invited to meet the tsadik of the Hasidim in Tzfat (Safed). The Hasidic master, who had come from the Ukrainian town of Ovruch, sang moving Shabbat songs at his table to ignite hitlahavut (inspiration) among his followers. Hasidic and Jewish folk melodies have also inspired some of Europe's best-known composers. In the nineteenth century, Mikhail Glinka included a Jewish song in his orchestral music for the tragedy Prince Kholmsky; Mussorgsky used a Jewish tune in his Pictures at an Exhibition and a Hasidic spiritual melody (nign) for his cantata "Joshua, son of Jesus"; and Gustav Mahler built the entire third movement of his First Symphony around an eastern European wedding dance tune (freylekhs). In the twentieth century, Ernest Bloch used Jewish liturgical and Hasidic music in several works: Solomon: A Hebrew Rhapsody, for cello and orchestra; Trois Poèmes Juifs, for orchestra; and Baal Shem, a suite for piano and violin.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.