Chapter 9.2: "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence"

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Chapter 9.2

Art ("classical") music

Since the introduction of Christianity into Kievan Rus' in the late tenth century, music has been an integral part of religious worship in Ukraine. The liturgy is sung or chanted, whether by a single voice (that of a priest or cantor) or by a choir and sometimes the entire congregation. As in other aspects of Ukraine's early church life, Byzantium provided models for sacred music and as the Rus' church was organized in the eleventh century it dispatched Byzantine Greek singers to train their counterparts in Kyiv.

The Eastern-rite church proscribed the use of musical instruments, based on the view that the Lord may be praised only with what He created — the human voice. In order to assure a steady supply of singers for the country's innumerable churches, centers for voice training were established in medieval Kievan Rus' and gradually were raised to high standards in subsequent centuries.

Church (vocal) music

As in Byzantium, church music in Kievan Rus' was mainly monodic; that is, it was characterized by a single melodic line chanted by three voices (one singing the melody and two drones) without musical accompaniment. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, under the impact of Polish composers, polyphonic singing was introduced in the Eastern-rite churches, in which the harmonic music may have had between four to twelve distinct voice parts with two or more melodies sung simultaneously. This complex Baroque-like style was described in a "grammar of musical song" by the Ukrainian composer and theorist of the time, Mykola Dyletskyi (Grammatika musikiyskago peniya, 1677), who also propagated the idea of large choruses performing a cappella (without instrumental accompaniment).

Choral music composition and performance reached its apogee in the eighteenth century. This was a time when the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy had its own orchestra of one hundred musicians and three hundred singers, and when a School of Singing was established (1738) in Hlukhiv, a small town in northern Ukraine. Hlukhiv, which at the time was the capital of the autonomous Cossack state, soon was to be headed by a generous patron of music and art, Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovskyi. It is from these institutions that Ukraine's first well-known composers (Maksym Berezovskyi, Dmytro Bortnyanskyi, and Artem Vedel) derive, although in the West they are commonly considered part of the first stage of modern Russian musical development. They invented the unaccompanied vocal concerto and produced a large body of polyphonic choral works for the church. Bortnyanskyi and Berezovskyi also composed orchestral works (mostly concertos) and Italianate operas based on themes from Greek mythology.

Orchestral and operatic music

The impact of Romanticism and the subsequent national awakening, with its interest in the common people and their creative capabilities expressed in folk music, had a great impact on Ukrainian composers. At a time during the nineteenth century when composers throughout Europe were trying to create a national school of music for their respective peoples (Czechs, Poles, Hungarians, Finns, Russians, among others), so did Ukrainians create musical works that drew on folk music and on themes that were presumed to be characteristic of Ukraine's past and present. Among the most popular works in this genre were the comic opera Zaporozhets za Dunayem (The Zaporozhian Cossack Beyond the Danube, 1863), by Semen Hulak-Artemovskyi, and an opera based on a poem by Ukraine's national bard Taras Shevchenko, Kateryna (1908), by Mykola Arkas.

The most successful composer of this period, whose music was consciously intended to inspire Ukrainian national pride, was Mykola Lysenko. He collected and published thousands of folk songs, some of which were used in his several stage works. The most popular of these was his operetta about young lovers in a rural village, Natalka Poltavka (The Maiden Natalka from Poltava, 1889), and an opera about the leader of an early-seventeenth-century revolt of Zaporozhian Cossacks against Poland, Taras Bulba (1890). In keeping with Ukraine's strong tradition of vocal music, composers from pre-World War I Austrian-ruled Galicia created in the Romantic mode the region's first Ukrainian operas — Anatol Vakhnyanyn's Kupalo (1892) and Denys Sichynskyi's Roksolyana (1909). At the same time, Stanislav Lyudkevych produced a series of choral compositions, the best known of which was a symphonic cantata, The Caucasus (1902–13), inspired by the poem of the same name by Taras Shevchenko. Art songs for vocal solo or duet with piano accompaniment based on poetic texts by Ukrainian as well as foreign authors were a particularly popular genre for the influential Mykola Lysenko and composers who followed in his footsteps during the first two decades of the twentieth century — Mykola Leontovych (best known in North America for his "Carol of the Bells"), Lev Revutskyi, Kyrylo Stetsenko, and Yakiv Stepovyi.

By the 1920s, Ukrainian composers were experimenting with the various avant-garde musical styles and techniques that had just begun to appear in western Europe on the eve of and during World War I. The relatively tolerant cultural atmosphere during the first decade of Soviet Ukraine's existence allowed for artistic experimentation, as in the expressionistic style and atonal technique of Borys Lyatoshynskyi; the unusual modal structures in the works of Mykhailo Verykivskyi; the Neo-classical orchestral suites of Viktor Kosenko; and the continuation of nineteenth-century Impressionism with a modern twist: rhythmic and melodic influences of Ukrainian folk songs and even American jazz, an example being the orchestral and choral works of Lev Revutskyi and Mykola Kolyada.

The new Soviet state's commitment to creating a modern industrialized society fit in well with the general European interest at the time in urbanism, that is, the transformation of cities so that they would have all the attributes of modernity: factories, sky-scrapers, automobiles, sleek trains, airplanes, and a generally accelerated, even frantic, lifestyle. In keeping with modernity, Ukraine's composers revealed their fascination with urban themes in compositions with titles like Three Hymns of the Industrial Epoch, Opera about Steel, and Automobile, whose scores incorporated the sounds and noises of machinery, planes, and cars, as well as syncopated rhythms from popular café, circus, and cabaret songs.

As was the case for other art forms, the relative freedom accorded musical life during the 1920s in Soviet Ukraine was curtailed in the following decade. From then on, composers were expected to abide by socialist-realist guidelines and to create orchestral works and music for stage (opera) productions that glorified Communist leaders and institutions, heroic workers, and ideologically sanctioned events, whether from the historic past or, preferably, more recent events from the Bolshevik revolutionary era. The goal was to produce music that was accessible to the masses. In effect, this meant the use of simple melodic material — whenever possible based on familiar folk songs — and banal subject matter emphasizing Soviet patriotism, class equality, and the struggle for worldwide peace. Virtually all Ukrainian composers who were recognized by the state authorities through their membership in the official Union of Soviet Composers (est. 1932) wrote, as a kind of self-imposed requirement for survival, songs about Stalin and scores for patriotic films.

But the ideal musical medium for conveying ideological messages — whether to the Communist party elite, local intelligentsia, or workers (who were frequently given free tickets for cultural excursions from their factory workplace) — was opera. Among the themes particularly encouraged by Communist party ideologists were those that dealt with the recent revolutionary era, as in Borys Lyatoshynskyi's operas about the Red Army's campaign to oust the counter-revolutionary Whites from Ukraine (Perekop, 1938) or about a Bolshevik military leader who died fighting the hated Ukrainian bourgeois-nationalists (Shchors, 1937–38). Historical themes from earlier times could also be refashioned to send an appropriate political message to contemporary audiences, especially if the seventeenth-and eighteenth-century uprisings against Poland were depicted as early examples of the masses in revolt against feudal oppression, as in the operas Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (1951–53) by Kostyantyn Dankevych, and The Haidamaky (1941), a joint effort of three composers.

Patriotic feelings were also expected to be the result of listening to oratorios composed by Mykhailo Verykivskyi, with texts about the Bolshevik Revolution (Oktyabrskaya/October, 1936) and resistance to foreign invaders (Hniv Slovyan/Anger of the Slavs, 1941), not to mention numerous other operatic and vocal works based on texts by Ukraine's leading nineteenth-century authors (Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesya Ukrayinka) as well as several ballets, the most frequently performed of which is to this day Lisova pisnya/The Forest Song (1941) by Mykhailo Skorulskyi. And since the Romantic folk-inspired repertoire from the nineteenth century could easily be understood by the "masses," the stage works of Hulak-Artemovskyi (The Zaporozhian Cossack beyond the Danube) and Lysenko (The Maiden Natalka from Poltava and Taras Bulba) were entered into the socialist-realist canon and given performances year after year in opera houses and conservatory stages throughout Ukraine until — and even after — the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Contemporary composers are fond of using traditional Ukrainian themes and folk music in symphonies, operas, and film scores in which otherwise familiar melodic songs are at times rendered in dissonant harmonic tones and experimental rhythmic patterns. In contrast to the past, modern-day Ukrainian composers like Myroslav Skoryk, Yevhen Stankovych, and Valentyn Silvestrov work as much abroad in the international musical world as they do at home. They have, however, not lost their interest in Ukrainian-inspired themes, including tragic ones of the twentieth century, such as Stankovych's large-scale orchestral oratorio, Kaddish-Requiem for Babyn Yar (1991).

Ukraine as a theme in classical music

Ukrainian subject matter and folk songs have also entered the music of composers from other countries, whose works are generally considered to be a major part of the repertoire of Western music. As early as the late-eighteenth-century classic period, Franz Jozef Haydn made use of a folk melody (kolomyika) from Transcarpathia in the "Hungarian Rondo" of his Piano Trio in G Major (1795), while just over a century later the modern Hungarian composer, Béla Bartók, who lived in that region on the eve of World War I, employed numerous Ruthenian folk melodies in his compositions.

It is perhaps not surprising that nineteenth-century Russian composers were especially drawn to Ukraine or, as they would say, Little Russia. Little Russian (that is, Ukrainian) folk songs were frequently used in either direct or stylized form by imperial Russia's most popular composer, Petr Ilich Tchaikovsky (himself a direct descendant of the Ukrainian Cossack Chaika family), as in his Second, or "Little Russian" Symphony (1872/80) and his opera Cherevichki (The Shoes, 1887). Other Russian composers were inspired by subjects connected with Ukraine, such as the "Great Gate of Kyiv," which is the title of the stirring finale of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (1874); or the "Polovtsian Dances," the exotic music from Aleksander Borodin's opera Prince Igor (1890) — the story of a Kievan Rus' prince and his battle against Turkic nomads on the steppes of twelfth-century Ukraine. Music from Borodin's operatic score and other works was later reused in the Broadway musical Kismet (1950). But the most popular Ukrainian theme was connected with the exploits (real, or more likely imagined) of the late-seventeenth-and early-eighteenth-century head (hetman) of the autonomous Cossack state, Ivan Mazepa. He became the subject of an opera (1883) by Tchaikovsky, a choral cantata (1862) by the Irish composer Michael Balfe, and an orchestral tone poem (1851) by the Hungarian Franz Liszt.

For other composers, their very presence in Ukraine was in and of itself enough to inspire musical creativity. Tchaikovsky recalled the weeks during several summers that he spent at the estate of his patroness (Madame von Meck) at Brayiliv in the Podolia region as the "happiest days of my life," which he subsequently immortalized in three pieces for violin and piano, Souvenir d'un lieu cher (Remembrance of a Dear Place, 1878). A few decades later, it was in Ukraine where two of the most seminal works in the history of modern music were conceived: L'oiseau du feu (The Fire Bird, 1910) and Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913), ballet scores by Igor Stravinsky written at his beloved family estate at Ustyluh in the Volhynia region of far northwestern Ukraine.

Jewish orchestral and operatic music

In the Russian Empire, Jews responded enthusiastically to the educational opportunities of the second half of the nineteenth century to integrate modernity not only through the liberal professions but also through the arts and, first and foremost, music. For example, whereas earlier in the century someone like Anton Rubinstein, born near Berdychiv, had to convert to Christianity in order to pursue the musical career that led to his founding the St Petersburg Conservatory, later in the century Jews did not need to conceal their Jewishness. Moreover, once the Romantic idea of folk art as a genuine national art won over the hearts and minds of the Jewish intelligentsia, Jewish musicians also became collectors (zamlers), in a sense ethnographic archaeologists who uncovered layers of previously neglected Jewish musical genres which they arranged for performance. Some also took an active part in the Society for Jewish Folk Music (the Kyiv branch of this body was established in 1913), which was dedicated to recording and publishing Jewish folk music.

The ethnographic study of Jewish folklore in the early twentieth century served as an intermediary between the folk music of the shtetl and modern Jewish music for the concert hall. Several musicologists devoted their careers to the study of the Jewish folklore of Ukraine. Yoel Engel from Berdyansk, who collected Jewish Yiddish songs, was instrumental in organizing the musical part of S. An-sky's 1911 ethnographic expedition to three Ukrainian provinces in the Pale of Jewish Settlement and later composed a chamber music suite for An-sky's The Dybbuk. An actual participant in An-sky's expedition, Zusman Kiselgof (Zinovii/Sussman Kisselhof), toured some sixty communities in Volhynia and Podolia, where he collected more than fifteen hundred folk songs and one thousand liturgical and orchestral melodies. The phenomenal trove of Jewish melodies (particularly nigunim) he uncovered eventually found their way into the operatic, symphonic, and choral works of several Jewish composers, including Lazar Saminsky from Odessa. In 1920 Saminsky moved to the United States, where he composed liturgical music and dozens of stylized Jewish folk dances and songs. Moisei/Moyshe Beregovskii, a musicologist at the Kyiv Conservatory who continued the work of earlier Jewish ethnographers, organized about two thousand expeditions across Ukraine in the 1920s to 1940s. These included both the devastated post-World War II communities and ghetto regions. Aside from cataloguing and transcribing the earlier collections of An-sky and Kiselgof, Beregovskii amassed a huge number of scores of musical pieces which had been used for performances of traditional Purim plays (Purimshpils).

The impact of secularization in the late nineteenth century created a rift between urbanized Jews and their tradition-minded brethren in the shtetls of the Russian-ruled Pale of Settlement. An attempt to bridge this gap led to the composition of quasi-shtetl songs which today are considered folkloric. These songs drew heavily on shtetl musical traditions, although they were created from the perspective of a purely urban environment like Kyiv. The most successful composer in this genre was a native of Odessa, Mark Varshavski, who wrote melodies and lyrics that resembled and were believed to be Yiddish folk songs. He performed these throughout the Pale at cultural and political (Zionist) gatherings together with the writer Sholem Aleichem who read his stories. Perhaps the most popular song among the Jews not only of Ukraine but all of eastern Europe was Varshavski's "Afn pripetshik" (On the Hearth). This and his many other songs, while actually conceived in an urban environment, were imbued with nostalgic longing for the world of traditional Jews.

Like S. An-sky, bilingual Yiddish-Russian writers from the Russian Empire, such as the Ukrainian-born Shimon Frug, considered the Ukrainian central provinces to be the cradle of genuine Jewish folkloric traditions. It was these traditions that inspired them to write the lines for what became the anthems of the two most important Jewish political movements in the decades before World War I: Frug did this for the Zionists, and An-sky for the social-democratic Bundists. Their anthems and other songs were used to rally the masses for political action. In neighboring Austria-Hungary, anthems came to symbolize political cooperation between Jews and Ukrainians. For example, in the Austrian imperial parliament, following the introduction of universal suffrage in 1907, it was not uncommon for Jewish and Ukrainian deputies from Galicia to rise and sing the Ukrainian national anthem together in response to the chauvinistic anti-Ukrainian statements of their political opponents, Galicia's Poles.

Composers of Jewish descent who made careers in Soviet Ukraine sought to become fully integrated into the country's musical circles; therefore, they only randomly resorted to using Jewish musical folklore in their work. There were both cultural and political reasons for such a decision, particularly since they were working under the restrictive government guidelines of socialist realism in literature and the arts. Nevertheless, they did not entirely ignore Jewish themes. For example, Solomon Faintukh, the author of several operettas and the director of a Ukrainian klezmer orchestra in the 1930s, wrote an oratorio, "Morys Vinchevskyi," dedicated to one of the leading American Jewish socialists, while Yakiv Tsehliar/Ziegler composed an oratorio titled "The Jewish Tragedy." These works remained, however, largely unknown to the general public.

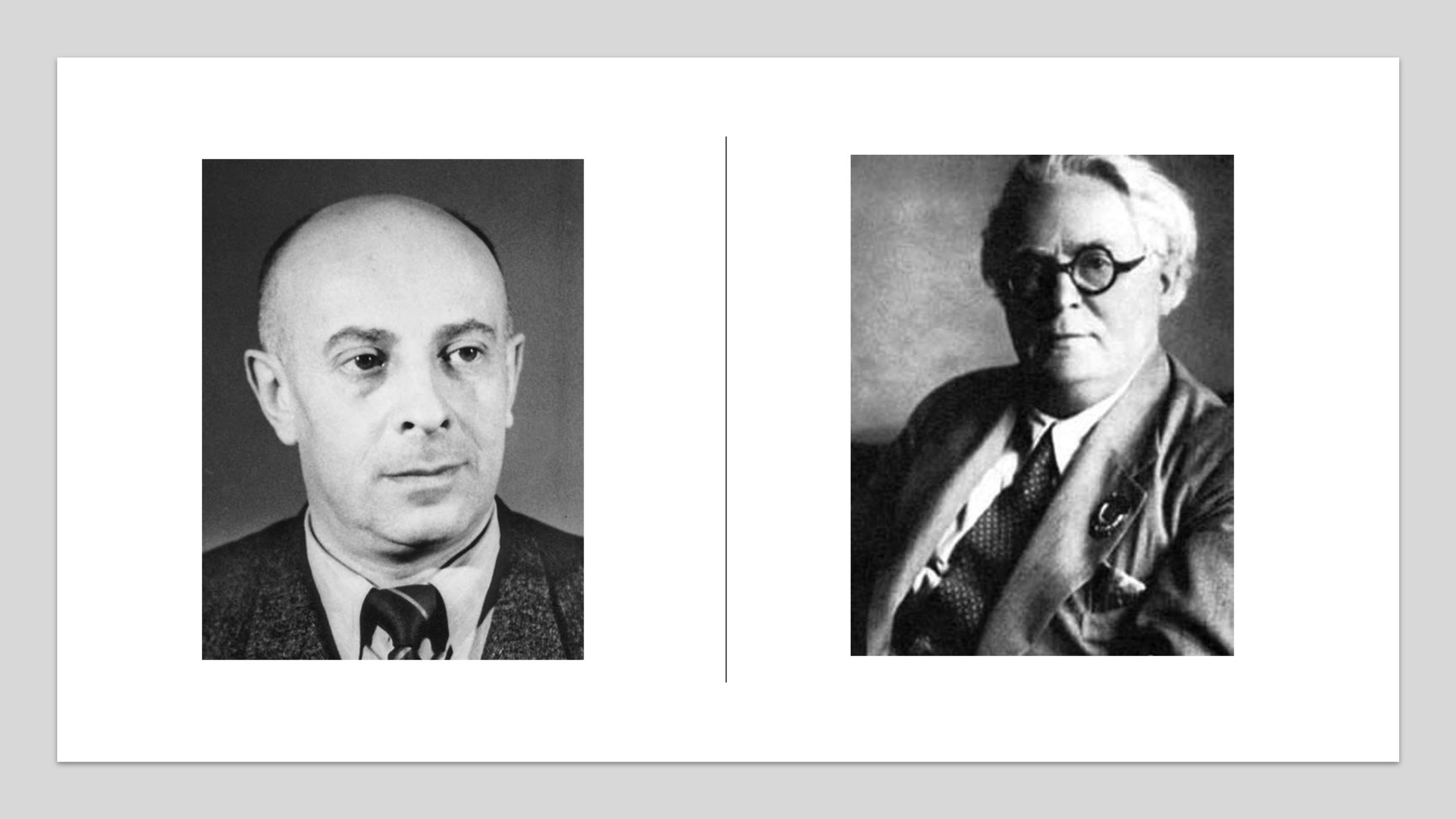

Even more evident for its Jewish-related content and, at the same time, its inaccessibility is the Symphony No.1 by a composer from Kharkiv of Jewish ancestry, Dmitrii Klebanov. Inspired by the September 1941 tragedy at the Babyn Yar ravine outside Kyiv, Klebanov depicted through musical themes the destruction of Jews at that killing site. For the Soviet regime, such an approach amounted to a serious ideological shortcoming, so that, after the symphony's two premieres (1947 and 1948), it was banned from public performance until the very last year of Soviet rule.

More successful in reaching audiences was Yulii Meitus, considered the father of Soviet Ukrainian opera. He used elements of Jewish folk music, although merging them — to avoid possible censorship — with Carpathian (Hutsul) musical motifs. This same approach to Jewish folklore was adopted by Ihor Shamo, the much-acclaimed author of Kyiv's anthem, "Yak tebe ne lyubyty, Kyyeve mii" (How Can One Not Love You, My Kyiv). Shamo also incorporated elements of Jewish klezmer music in his symphonic compositions on Hutsul, Moldavian, and Carpathian themes. Paradoxically, it was one of the Soviet Union's leading composers, Dmitrii Shostakovich, who widely used Jewish folk motifs and songs collected by the renowned Ukrainian-Jewish ethnomusicologist, Moisei Beregovskii. As a result of his participation on Beregovskii's dissertation committee and access to the entire corpus of material collected by the Kyiv-based ethnomusicologist, Shostakovich was able to make use of Jewish traditional music in some of his own works: the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry (1948), the Piano Trio no. 2 (1944), and the String Quartet no. 8 (1960), not to mention his monumental Symphony No.13 (1962) for orchestra and chorus, which incorporated the words of Yevgeny Yevtushenko's politically radical (in the Soviet context) 1961 poem, "Babi Yar."

Renowned teachers and performers

Jews

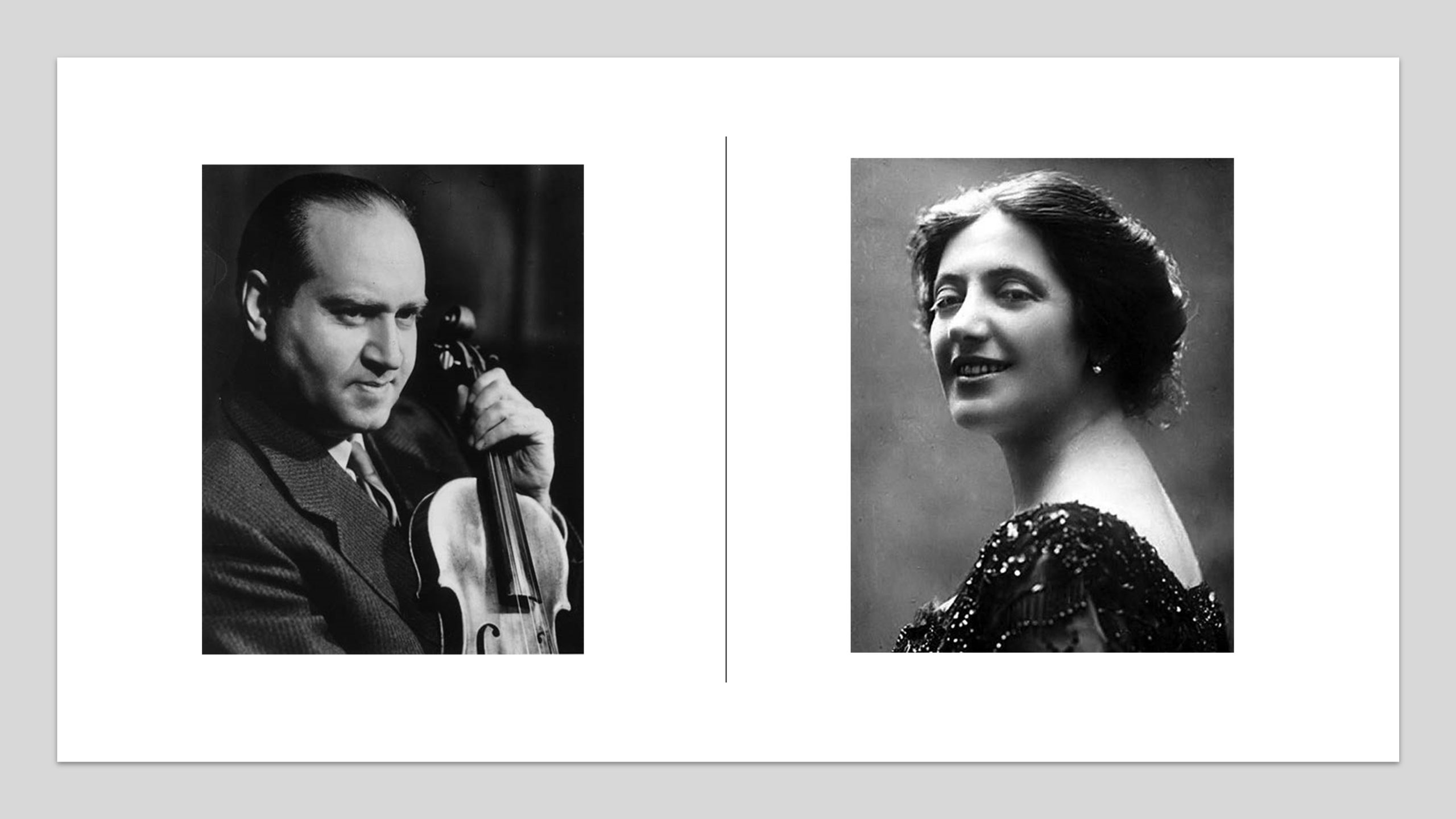

The Jews in the Russian Empire and later Soviet Union absorbed the best elements of high urban culture. Many entered conservatories where they mastered a variety of musical instruments, in particular those suitable for virtuoso performance. By the early twentieth century, Jews were particularly well represented among teachers of piano, the instrument that — after the shtetl violin — became a marker of a civilized Jewish household. From Ukrainian lands came in the course of the twentieth century several Jewish pianists of world fame. Vladimir Horowitz from Kyiv and Emil Gilels from Odessa were both known for their unbridled romanticism, bold interpretations, and rich dynamic contrasts. Among renowned players of string instruments of Jewish background from Ukraine were Gregor Piatigorsky from Katerynoslav/Dnipropetrovsk, one of the most celebrated cellists of the twentieth century, and Misha Elman, the grandson of a klezmer violinist from Talno who made a dazzling career in Europe and America. The two best schools for studying the violin in Ukraine were linked to the names of Pyotr Stolyarsky in Odessa and Yakov Magaziner and David Bertie in Kyiv, who taught several generations of outstanding eastern European musicians, including Mikhail Fikhtengolts, Elizaveta Gilels, Nathan Milstein, David Oistrakh, and Abram Shtern.

Several of the Soviet Union's most popular songwriters of the mid-twentieth century were of Ukrainian Jewish descent. Already in childhood, they were exposed to Ukrainian, Jewish, and Gypsy folklore, as well as to urban street songs. In many cases, before they became celebrated composers, they sang in synagogues, danced in the streets, and performed at cabarets. Among the best known to Soviet audiences were Matvei Blatner from Chernihiv province, Isaac Dunaevsky from Lokhvytsya, Leonid Utesov from Odessa, and the four Pokrass brothers from Kyiv, particularly Daniil and Dmitrii. All infused Soviet music with an outward frankness of expression and melodrama drawn from Ukrainian musical folklore, the soft irony of Jewish themes, and the characteristic Odessa-style articulation of lyrics. In addition, they were the first to introduce jazz into the Soviet Union's music repertoire.

Jews are still remembered for their influential role in Soviet musical life. Hence, in the 1970s, Israelis liked to joke that if a new immigrant (ole) arriving at the Tel Aviv airport did not have a violin case under his or her arm, then that person must be a pianist. The contribution of Jewish artists to Soviet musical culture is celebrated in present-day independent Ukraine. In 1991 the Vladimir Horowitz Piano Competition was established in Kyiv, and, most recently, the Odessa city council approved a decision to establish a monument to David Oistrakh in the center of the city, which will join the monument to the singer, musician, movie star and jazz-band director of Jewish descent, Leonid Utesov (Lazar Vaisbein).

Ethnic Ukrainians

Coming as they did from a long tradition of church choral singing, it is perhaps not surprising that ethnic Ukrainians have excelled as vocalists. Ukraine's century-long Italian bel canto tradition and training produced a wide range of prodigiously talented singers, who since the late nineteenth century have performed on the leading operatic stages of Europe and North America. The most renowned are Solomiya Krushelnytska, Borys Hmyrya, Ivan Kozlovskyi, Yevheniya Miroshnychenko, Anatolii Solovyanenko, Anna Netrebko, and the émigré-born Paul Plishka and Pavlo Hunka. Aside from their stage appearances, these artists have performed chamber recitals and most have left a wide body of recordings. Some have even "crossed-over" and recorded soundtracks for movies.

Among violinists trained under Stolyarsky, Magaziner, and Bertie in Odessa and Kyiv are the ethnic Ukrainian performers and teachers Olha Parkhomenko and Oleksii Horokhov. The Kyiv Conservatory has trained a highly acclaimed group of pianists going back to the nineteenth century (Volodymyr Pukhalsky, Vsevolod Topilin, Tatyana Kravchenko, and Vitalii Syechkin), and it has also produced a new school of musicians from western Ukraine, including Bohodar Kotorovych and Oleh Krysa, known for their performances in Ukraine and abroad.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.