Compelling book describes heartbreaking difficulties of mass migration of Eastern European Jews

Who closes the door? And who can open it? Who escapes? And who doesn’t?

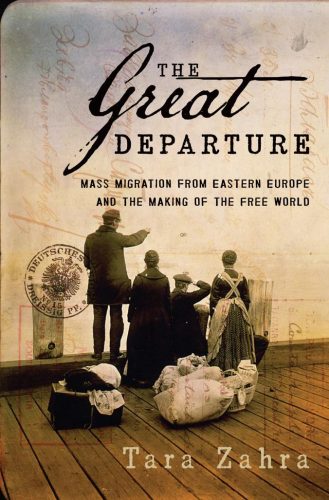

A compelling book entitled The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World by Tara Zahra answers some of these questions.

Tara Zahra is a professor of modern European history at the University of Chicago and a recent winner of a MacArthur Fellowship. Her book is an impressive work of scholarship that is filled with often-heartbreaking personal stories of the devastating human toll of migration.

Between 1846 and 1940 more than fifty million Europeans moved to the Americas in one of the largest migrations of human history. Villages were emptied out throughout Europe—especially Central and Eastern Europe. The homes the emigrants left behind as well as their new homes were fundamentally changed.

From almost the very beginning emigration policies were political tools to be manipulated and exploited. Governments and nationalist movements were eager to see certain groups leave—they were often called “surplus populations”—while trying to restrict the departure of other “favored groups” considered essential for state or nation building. The goal was to create nationally homogeneous populations. A goal pursued by various regimes and governments into the twenty-first century.

Therefore, Professor Zahra’s research shows the vast majority of the 2.7 million imperial Russian subjects who left the Tsarist Empire between 1880 and 1910 were Jews, Polish-speakers, or German-speakers.

Therefore, Professor Zahra’s research shows the vast majority of the 2.7 million imperial Russian subjects who left the Tsarist Empire between 1880 and 1910 were Jews, Polish-speakers, or German-speakers.

Russian imperial authorities began to encourage Jewish emigration in the 1890s. The government let the Jewish Colonization Association set up branches throughout the empire in 1892. Emigration remained illegal for non-Jewish subjects of the tsar.

Brody, a western Ukrainian city that was then on the frontier of the Russian and Austrian empires, entered folklore as a major door of departure to a new life.

Brody itself was on the fringe of Galicia, a Habsburg Austrian crown land notorious for its abject poverty. Unlike Russia, all citizens of the Habsburg Empire had the constitutional right to leave. The Ukrainian and Polish peasants of Galicia, along with the region’s Jews, also emigrated in massive numbers to new overseas opportunities. Authorities recorded a total of 3.5 million emigrants from throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire to all overseas destinations between 1876 and 1910. The largest numbers left from Galicia and Bukovina and from southern and eastern Hungary. Almost three million went to the United States.

The powers that be became alarmed. There was an increasing shortage of young men to call up for military service. Polish and Hungarian nobles in the Habsburg Empire feared losing cheap agricultural labor to American factories and mines.

The nobles had reason to worry. Wages in Western Europe and the United States were two to three times higher than wages in Galicia. And in those areas of Galicia most affected by emigration, wages eventually had to rise as employers had to compete in a global marketplace. Furthermore, as Professor Zahra points out, the tremendous flow of remittances from Galician emigrants back to their homeland expanded peasant landholdings, renovated churches, and provided economic relief.

Massive emigration, especially of young women, provoked fears, if not a moral panic. Professor Zahra notes the Austrian antisemitic press linked emigration and sex trafficking to criminalize Jewish emigration agents. There were sensational “white slavery” trials—including one in Lviv in 1892—and lurid press reports.

The Austrian-Jewish feminist Bertha Pappenheim—also renowned as the patient Anna O. in Sigmund Freud’s case study—traveled to Austrian Galicia in 1903 to gather information about sex trafficking. She expressed concerns about the ignorance of migrants, unscrupulous agents, and every girl’s vulnerability to “all forms of danger and vice.”

Sincere emigration reformers concerned about the exploitation of Austro-Hungarian citizens overseas also stirred fears, as Zahra writes, “that East European men and women would be treated like nonwhite colonial labor, Chinese “coolies,” or enslaved Africans.

Professor Zahra argues that both anti-trafficking and anti-emigration reformers tended to ignore the underlying economic conditions that prompted emigration, as well as the agency of individual migrants.

The book goes far beyond the pre-1914 era to show how a template was set for future dramatic events in the twentieth century. The author explains how the policies that shaped this original great migration provided a precedent for bureaucratic “paper walls” that doomed Europe’s Jewish population from escaping the Holocaust, the closing of the Iron Curtain, and ethnic cleansing. The author places the current refugee crisis within the longer history of migration.

Professor Zahra notes, “every Great Departure comes with its own choices, anxieties, and disappointments. States make choices about whether to welcome newcomers or build new barriers, whether to encourage departures or returns. Individuals, meanwhile, are forced to make tortured choices between pressing onward or returning home.”

As for those choices, she reminds us “it matters a great deal whether the decision to live abroad is made out of desperation or of ambition.”

The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World by Tara Zahra is published by W.W. Norton. It is also available on Amazon.

From San Francisco, I’m Peter Bejger. Until next time, shalom!

Written and narrated by Peter Bejger.

Listen to the program here.

Ukrainian Jewish Heritage is brought to you by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a privately funded multinational organization whose goal is to promote mutual understanding between Ukrainians and Jews. Transcripts and audio files of this and earlier broadcasts of Ukrainian Jewish Heritage are available at the UJE website and the Nash Holos website.