From conflict to cooperation: Ukrainian-Jewish relations’ bumpy path

For much of the history of Ukraine, it was difficult to speak of anything akin to Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Jewish assimilation into the broader Ukrainian society was always a complex issue, but myriad connections and positive contacts between the Ukrainian and Jewish national movements always existed.

This essay appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of The Odessa Review, which was supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Until the second half of the 19th century, Jews living in the Ukrainian provinces of the Russian Empire barely participated in politics and civic society outside their own communities. Their first efforts to exit this intellectual isolation date back to the epoch of Czar Alexander II’s “Great Reforms”, when Russia eliminated serfdom and took steps to modernize society and the economy. During this period, the first magazine intended for “acculturated”, enlightened Jewish readers appeared in Ukraine. Because it was published in Russian, the magazine — first titled Dawn (1860-1861) and then Zion (1861-1862) — targeted an audience quite far from the majority of the Jewish population, which largely adhered to its traditional folkways.

This newfound Jewish intellectual ferment provoked the first conversations with the growing Ukrainian national movement and set into motion a discussion that has continued, on and off, to the present day.

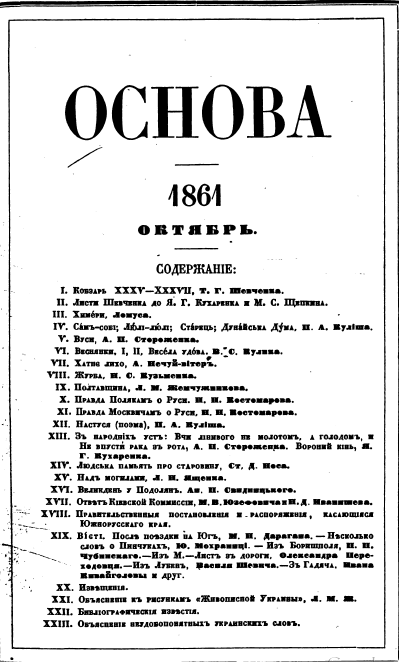

In 1860, a young doctor named Veniamin Portugalov — a man connected to both the Jewish and Ukrainian movements — wrote to the editor of the Ukrainian monthly Osnova to protest against its authors’ usage of the word “zhyd” (“Yid”) in Ukrainian-language texts. The word has been long regarded as an antisemitic slur in Russian, but historically much less so in Ukrainian.

Panteleimon Kulish, a prominent Ukrainian writer and intellectual, responded to Portugalov, arguing that he saw nothing offensive in the word. Although Kulish refused to change Osnova’s editorial policy, his answer sparked a lengthy discussion that spilled over into several of the era’s leading literary journals and covered far more than the proper term for “Jew”.

In 1881, Alexander II was assassinated by the People’s Will revolutionary movement. The Czar’s killing proved a disaster for the Empire’s Jews, who were blamed for the murder. A wave of pogroms erupted in the empire’s western provinces. This anti-Jewish violence, in turn, gave impetus to increased Jewish political activism and literary activity.

But Jewish activists were not simply responding to a series of pogroms. Rather, something had changed in the empire’s politics. Unlike in previous (and subsequent) periods, anti-Jewish sentiment was now widespread both in the revolutionary movements and the pro-government ones. The underground presses of the People’s Will and Black Repartition revolutionary parties treated the pogroms as the people’s just reaction to “Jewish exploitation”. In the first months of the wave of violence, People’s Will even published a leaflet titled “To the Ukrainian people”, which featured openly pro-pogrom propaganda. Only later, in 1882, did exiled members of Black Repartition issue a condemnation of the pogroms as an antisemitic phenomenon.

The government and its supporters also largely shared the revolutionary assessment of the pogroms. In 1882, the authorities forbade Jews to settle in rural areas, except for Jewish agricultural settlements. Because small towns — where large numbers of Jews lived — were already overcrowded, these new restrictions led many Jews to migrate to cities or emigrate from the empire.

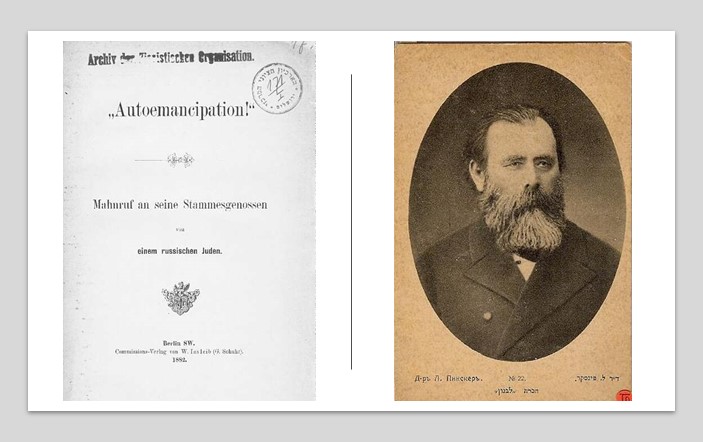

Until the cataclysmic events of 1881-1882, many authoritative Jewish figures advocated achieving civil equality (emancipation) and culturally assimilating. But the pogroms and new restrictions on the Jewish populations led many to change their minds. In 1882, Leon Pinsker — formerly the editor of the Dawn/ Zion magazine and a decades-long advocate for Jewish equality — published Auto-Emancipation. The book’s very name made its central thesis clear: Jewish liberation must be the work of the Jews themselves. In 1884, Pinsker founded Hovevei Zion (“Lovers of Zion”), an organization that aimed to improve the Jewish predicament through emigration to Palestine. Like the Zionist Organization, which would be founded a few years later, the “Palestinophilic” Hovevei Zion barely paid attention to the issues of relations between Jews and the Ukrainian and Belarusian populations of the Russian Empire.

The Yiddishist cultural and linguistic movement took a different view. It’s supporters saw the Jewish future in the diaspora and advocated Jewish equality within the empire’s western provinces. Yiddishists grouped around contemporary Yiddish-language newspapers, including those published by “Palestinophiles” — for example, the St. Petersburg paper Yidishes folksblat, published by Alexander Tsederbaum.

Although Yiddish newspapers in the late 19th century were primarily printed outside Ukraine, many of their readers resided there. The very appearance of Yiddish-language mass media reflected a substantial change in the language’s status. It transformed from “jargon” — as intellectuals, both Jewish and non-Jewish, termed it — into a full-fledged language capable of describing all subjects important to its speakers.

The status of Yiddish-speakers also changed. Previously, the path out of the traditional Jewish community was language assimilation or, at least, acculturation into a non-Jewish environment. Now, Jewish people could retain their language after leaving the shtetl for work in the city. This scenario, however, was more characteristic for Belarus, Poland, and Lithuania, where the proportion of Jews in the labor force was noticeably greater. By comparison, urban Jewish workers in the Ukrainian provinces quickly Russified. Jewish integration into broader society was not without friction. When Jewish workers started forming their first trade unions, workers’ self-help funds, and other organizations, they came into conflict with non-Jewish workers. This was especially noticeable when employers used non-Jewish workers to break strikes by Jewish workers, or vice versa. Soon, however, non-Jews began to copy the forms of Jewish workers’ self-organization, and trade unions became common for both populations. This helped to reduce tensions between ethnic and religious groups within the urban population.

After the 1903 Kishinev pogrom (in today’s Chisinau, Moldova) and the wave of pogroms in 1905-1906 in Ukraine, Jewish political life again intensified. Political parties received legal status. This time, attitudes toward the pogroms clearly divided Russian society. The liberal public and activists from revolutionary organizations sharply condemned anti-Jewish violence. Meanwhile, right-wing circles — with rare exceptions — treated the pogromists favorably. The Ukrainian political organizations created in these years seldom raised this issue in their publications, but the Ukrainian non-partisan press — and particularly Rada, the largest Ukrainian newspaper — sharply condemned antisemitism.

During and after the 1913 trial of Menahem Mendel Beilis, a Kyiv Jew who was groundlessly accused of murdering a Ukrainian child for ritual purposes, Ukrainian-language newspapers and magazines regularly published articles debunking the “blood libel” myth. Such articles were even published in Ukraine’s western Galicia region, farther from the epicenter of the story. Nearly the only exception to the Ukrainian press’ tendency to side with Beilis was the newspaper Ridniy Krai (1908-1914), published in Poltava by poet Olena Pchilka (the mother of Lesia Ukrainka, one of the greatest Ukrainian poets). She herself wrote a number of openly antisemitic articles for the newspaper.

But for all the growth in Jewish social and literary life, it was not accompanied by the intensification of cooperation between Jewish and Ukrainian political organizations. Almost all the elected Jewish deputies in the State Duma represented the most influential all-Russian liberal political force, the Constitutional Democratic Party. Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, an Odessa native who would go on to found Revisionist Zionism, sharply condemned this political orientation towards the imperial center.

Between 1914 and 1917, the Russian Empire banned both the Jewish press in Yiddish and Ukrainian-language periodicals. But with the eruption of the February Revolution in 1917, both the Jewish and Ukrainian political movements experienced a new round of activity. That summer, representatives from the Jewish, Polish, and Russian minorities’ political parties were co-opted into short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic’s Central Rada and its executive body, the General Secretariat.

Despite this, cooperation between Ukrainian and Jewish political parties was far from smooth. During the vote on declaring the Ukrainian People’s Republic’s independence, the majority of the Jewish deputies abstained, while the faction from the Jewish Bund voted no. According to Solomon Goldelman, a Ukrainian and Jewish politician from the Poalei Zion (“Workers of Zion”) party, this was perceived by many Ukrainians as a hostile act.

A new wave of pogroms in 1919 significantly dimmed the prospects of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Many Jewish national figures began to perceive the Ukrainian movement as a movement of pogromists. After the 1926 assassination of Ukrainian statesman Simon Petliura by Jewish anarchist Shalom-Shmuel Schwarzbard, antisemitic ideas spread widely in right-wing circles of the Ukrainian national movement in exile.

In this regard, during the 1920’s and 1930’s, Ukrainian-Jewish cooperation was largely confined to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Under its nativization policies, the Soviet Union created in Ukraine three Jewish national districts; hundreds of Jewish primary schools, pedagogical institutes and agricultural technical schools; Jewish departments in universities with teaching in Yiddish; and the Institute of Jewish Proletarian Culture of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. The USSR translated the classics of Yiddish literature into Ukrainian, and anthologies of Ukrainian Soviet prose and poetry were published in Yiddish.

However, the Jewish component of nativization decayed in 1934, after the Soviet Union created the Jewish Autonomous Region in Russia’s far east. And all of its achievements came to naught in 1938, when the authorities officially liquidated the national districts and eliminated schools teaching in minority languages.

During the Second World War, Adolf Hitler largely wiped out Ukrainian Jewry. The voluntary (and also involuntary) participation of some Ukrainians in Nazi atrocities against Jews greatly influenced the image of Ukrainians as antisemites among Jews in the West. The cases in which Ukrainians saved Jews during the war were comparatively and proportionally small and the role of Ukrainian soldiers in the Allied victory over Nazism, though significant, was (and remains) largely ignored. The victorious soldiers were widely perceived as “Soviet” or “Russian”.

Even literary works challenging stereotypes about Ukrainian-Jewish relations failed to leave a mark. Yiddish poets like David Gofshteyn and Itzik Fefer dedicated their WWII-era works to Ukraine, but these were banned during the Stalinist persecution of Jews. Similarly, “To the Jewish People”, a poem by Soviet Ukrainian poet Maksym Rylsky was only published during Perestroika. These works even went virtually unnoticed among émigrés.

A new round of positive contacts between the Ukrainian and Jewish national movements began in the 1960’s. Representatives of Soviet Jewish movements, particularly the refuseniks, who finding themselves in the gulags came into close contact and dialogue with Ukrainian national dissidents.

After emigrating from the Soviet Union, prominent Jewish journalists such as Mikhail Kheyfets and Israel Kleiner worked closely with the liberal wing of Ukrainian emigration to publish valuable books on the history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

In theory, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 could have led to a full-scale revival of Jewish national culture in Ukraine. However, given the region’s history, that was not possible. The Yiddish language had been almost completely lost decades ago. And with the dissolution of communism, the Jews of Ukraine massively repatriated to countries that included Israel, America and Canada.

But despite the small number of Jews left in the country, they continue to occupy a prominent place within Ukrainian cultural life. And many Ukrainians who do not have Jewish roots participate in the restoration and conservation of Jewish cultural heritage sites, study Yiddish, and translate and publish the forgotten or overlooked texts of Jewish writers. They understand this to be a part of their country’s history and provenance. As in previous periods, cooperation between Ukrainians and Ukrainian Jews continues. Only now it assumes forms that were previously impossible.

Serhiy Hirik is a historian and a senior lecturer at the MA in Jewish Studies program of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. He is also the secretary of the Ukrainian Association for Jewish Studies.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.