Contemporary antisemitism in Ukraine

[Editor’s note: The newest installment of “The Odessa Review” focuses on Ukrainian-Jewish relations, past present and future. The Ukrainian historian Serhiy Hirik has penned two essays for this latest edition, which was published with the support of the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter. Below is an interview with Hirik that aired recently on Hromadske Radio’s “Zustrichi” program.]

A conversation with the historian Serhiy Hirik, a member of the faculty in the Master in Jewish Studies program in at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, on antisemitism in everyday life, politics, and media in Ukraine.

Andriy Kobalia: Let’s start with this question. In 2014 Josef Zissels said in Berlin that the problem of antisemitism in Ukraine is irrelevant and not that significant. He had in mind that we do not have political parties or movements that support antisemitism. Do you agree with this thesis, and has something changed since 2014?

Serhiy Hirik: I agree somewhat with this thesis because manifestations of violent antisemitism and cases of antisemitic vandalism on the territory of Ukraine occur on a significantly smaller scale than in the countries of Western Europe. Such incidents in Ukraine are monitored by the National Minority Rights Monitoring Group, which is headed by Vyacheslav Likhachev. They record twenty to thirty such incidents per year, which is many times less than in the majority of European countries. But first of all, the number of such incidents is growing. Secondly, unlike Western Europe, many varieties of non-violent antisemitism on the territory of Ukraine are not criminalized, for example, Holocaust denial. This circumstance is paving the way for such excesses to occur in the future.

Andriy Kobalia: You mentioned that manifestations of antisemitism are statistically very significant in Western Europe, especially in Germany. What is the reason for this? Why is antisemitism more prevalent in some societies, and why is it less prevalent in others? Why is it such a problem in Germany?

Serhiy Hirik: One cannot say that it is higher than in Ukraine. The level is approximately the same. The issue is, rather, that it is acquiring somewhat different forms. There, it translates into incidents of violence—attacks on religious Jews—or in the form of antisemitic graffiti. It is not case that they are painted exclusively by antisemites. Some of them may have been painted exclusively by hooligans. On the territory of Ukraine, antisemitism is not acquiring these forms, but on the everyday level there are no fewer antisemitic stereotypes. Perhaps even more. There are fewer acts of hooliganism by antisemites, and the question is less politicized.

Serhiy Hirik: One cannot say that it is higher than in Ukraine. The level is approximately the same. The issue is, rather, that it is acquiring somewhat different forms. There, it translates into incidents of violence—attacks on religious Jews—or in the form of antisemitic graffiti. It is not case that they are painted exclusively by antisemites. Some of them may have been painted exclusively by hooligans. On the territory of Ukraine, antisemitism is not acquiring these forms, but on the everyday level there are no fewer antisemitic stereotypes. Perhaps even more. There are fewer acts of hooliganism by antisemites, and the question is less politicized.

Andriy Kobalia: Are the statistics recorded for both Germany or Ukraine for example, reliable? Are reports on Ukraine qualitative? Or is it possible that a certain number of manifestations of antisemitism has not been documented?

Serhiy Hirik: After the emergence of the group that is headed by Vyacheslav Likhachev—while he lives in Jerusalem he does have associates, including Tatiana Bezruk and others, in Ukraine—we can say that our information is quite representative.

Andriy Kobalia: This organization works with governments, providing for example reports to the German government?

This is a Ukrainian organization and publishes its materials regularly, but on this question it is better to contact Vyacheslav Likhachev, who is always completely open to cooperation and discussion.

Andriy Kobalia: Can you offer examples of some countries that at one time experienced a high level of manifestations of antisemitism, but whose governments or public organizations found methods that were able to cope with this problem over time?

Serhiy Hirik: In my opinion, it is not possible to overcome antisemitism completely. There is a possibility of channelling its manifestations into a less dangerous direction, particularly via criminalization. Or through awareness-raising work, explaining to the population why, for example, the construction of a monument to Svyatoslav in Mariupol is a manifestation of antisemitism, seeing as Svyatoslav Ihorevych is glorified above all for vanquishing the Khazars, and this is connected with the so-called “Jewish-Khazar myth,” as put forward by antisemites.

Andriy Kobalia: Does Ukraine have legislation that criminalizes manifestations of antisemitism?

Serhiy Hirik: There is a general article on the “Prohibition of Propaganda of Racial and National Hatred,” which includes a ban on antisemitic propaganda. Despite this, the two most widespread forms of antisemitism on the propaganda level—Holocaust denial and so-called “anti-Zionist propaganda”—are not criminalized at all and do not even entail administrative responsibility. In the first case, it is difficult to establish a line between freedom of speech and ethnic intolerance. The second case is the same: Where is normal political propaganda and criticism of concrete actions on the part of the State of Israel, and where does anti-Zionism as a kind of ban on the right of Jews to self-determination and criticism of the very possibility of the existence of the State of Israel begin? The majority of manifestations of “anti-Zionism” are antisemitic, and “anti-Zionism” is simply a cover for antisemitism. Sometimes, however, this is absolutely normal left-liberal criticism of the concrete actions of the State of Israel.

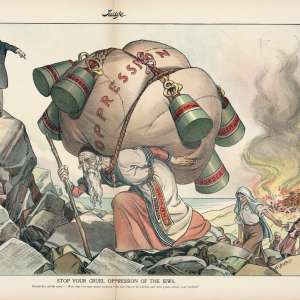

Andriy Kobalia: Speaking about the level of antisemitism on the grassroots level, I often see in everyday life that some Ukrainians try to shift responsibility for their problems onto other population groups. For example, they are not to blame for their low salary, it’s “someone else.” And very often Jews are this “someone else.” I know that this logic is applied not just in contemporary Ukraine. Similar things existed in the Russian Empire, too. I have seen websites—not only Ukrainian—who blame a high proportion of Jews in Parliament, for example, as the source of problems, and this is absurd. But why is there need to blame others, and why are Jews, specifically, accused most often?

Serhiy Hirik: The search for another is generally a very convenient explanation of any problems. Where the application of conspiracy theories to Jews is concerned, there is a quite a long tradition behind it, starting in the eighteenth century, when conspiracy theory began to be used with regard to the Masons, who were not being connected yet to the Jews. The latter, in fact, were not allowed to join Masonic lodges even in the early nineteenth century, when the term “Judeo-Masonry” appeared. Because the Masons used symbols connected with the Bible, the Masons began to be perceived as the spokesmen of Jewish interests. This is a very convenient explanation. The Jews lived apart. For religious reasons, they could not interbreed with Christians without converting. To a certain extent, a proportion of Jews preserved their identity even after conversion.

Andriy Kobalia: I think that a significant role is played by the myth that all Jews are prosperous, even though it is generally known that a significant proportion of Jews lived as poorly as Ukrainians or Russians.

Serhiy Hirik: What is important here is the circumstance that Jews who were well off were culturally assimilated and lived mostly among the local non-Jewish population in large cities, while poor Jews lived in small towns. Although they had frequent contact with the local non-Jewish rural population, in cities, where this stereotype was spreading, they put in an appearance only at fairs..

Kyiv, for example, was encircled by the Pale of Settlement, but as an important strategic city, owing to the presence of the Kyiv Fortress, it was closed to Jews, who had no right to reside outside the Pale of Settlement. Only Jews with a higher education or merchants of the first guild enjoyed these rights. Accordingly, they occupied a high social position and antagonized the non-Jewish part of the population of Kyiv. For Jews, Kyiv was a closed enclave that was located in a territory where Jews could, for example, live in the city suburbs.

Andriy Kobalia: Jokes are an important element in the everyday antisemitism of contemporary Ukraine. Can one say that jokes about a “Ukrainian, a Russian, and a Jew” preserve myths and stereotypes? Why do jokes like this arise in the first place?

Serhiy Hirik: This is a question for the folklorist or culturologist, but first of all, jokes and other types of urban folklore simply reflect stereotypes, and very often they mirror the stereotypes that are prevalent in society. Second, jokes by their very specificity are extremely variable. Jokes about the same subjects exist in a certain locale in one form featuring the representatives of certain nationalities, and in another locale the same roles in the joke are performed by other nationalities. Jokes comprise a wandering genre. The situation changes, and another nationality carries out this role. For example in Israel the Arab can take on a role in jokes, while in Ukraine a Russian or somebody else can take a role.

Andriy Kobalia: In switching from the everyday level [of antisemitism] to education, I mentioned that you spoke about awareness-raising work with the population. Is enough being said about the history of Ukrainian Jews in history classes in schools?

Serhiy Hirik: We should talk not only about the Jews, but also treat the teaching of Ukrainian history not as the history of exclusively ethnic Ukrainians, but as the history of the territory of this state, in which ethnic Ukrainians occupy a separate and largest niche, Russians occupy a separate niche, and Jews, who left behind a cultural legacy in this territory and were present in cultural and public life, etc., occupy a separate niche. Overcoming this imbalance will help bridge this chasm between the Jews, those few who remain, and the rest of the local population.

Andriy Kobalia: So the history of not only Jews, but of all minorities who have lived on the territory of contemporary Ukraine?

Yes. I remember that when I was in school, the history of the Crimean Khanate was studied in the seventh and eighth grades as part of the world history curriculum. I remember this from the textbooks. At the present time relevant paragraphs have been incorporated into Ukrainian history textbooks. For the future de-occupation of the Crimea, this change is very important. But this happened only after the occupation, as far as I know.

Andriy Kobalia: I am aware that these subjects also appear in semi-popular literature. A recently published book called The History of the Ukrainian Army features a chapter on the Crimean Khanate.

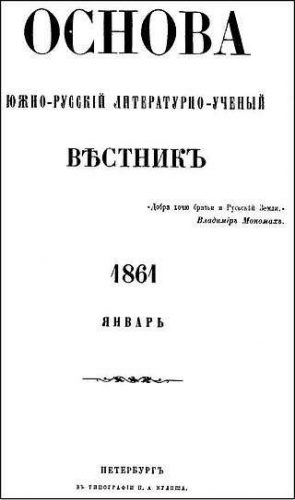

I often hear that Jews can be called by another word. When someone says that this word [zhyd] is insulting to Jews, the immediate response is that this is a normal and not insulting word and that’s how Jews are called in western Ukraine. This issue has been topical since the conflict between the journals Sion and Osnova erupted in the 1860s, when the question arose of how to call Jews correctly—by the word “yevrei” or that other word. What is the correct nomenclature?

Serhiy Hirik: People should be called the way they want to be called. For the majority of Jews, the word “zhyd” is insulting. Thus, it should be avoided simply out of respect for concrete individuals. The polemic between Sion and Osnova revealed the fact that a Russian-speaking journalist of Sion perceived the folkloric texts published in Osnova, which used this word, through the prism of his proficiency in Russian, not Ukrainian. At the time this word did not have offensive connotations in the Ukrainian language, but he perceived them as a Russian-speaking individual. Later, this word acquired an offensive meaning in Russian-ruled Ukraine. That is why in the early twentieth century we see the complete dominance of the word “yevrei” among Ukrainian cultural figures. The situation was different on the territory of Galicia. There, the word “zhyd” was dominant because of the influence of the Polish language, where only this word was used, and thus it was used by Galician Ukrainian cultural figures. It was only after 1917 that the word “yevrei” begins to predominate in the Dnipro region and beyond the confines of the narrow stratum of cultural figures, but in Galicia this happened only after 1939 and the war. For example, in the first edition of his brochure Who Are the Ukrainians and What Do They Want, Hrushevsky uses the word “zhyd,” but in the second edition (1918) he uses the word “yevrei.”

Andriy Kobalia: You mentioned that in western Ukraine the word “zhyd” is tied to the Polish language…

Serhiy Hirik: The conservation of its use…but its origin is much earlier due to Polish influences. But the fact that it was not replaced by the term “yevrei” is tied to the fact that in the Polish language that is the only normative term for “Jew.”

Andriy Kobalia: And it is not considered an offensive term in the Polish language?

Serhiy Hirik: Yes, because there is simply no other term for a Jewish person. The word “yevrei,” the root word “hebraj,” does not exist in the Polish language as term for a Jewish person but is used only a reference to the Hebrew language.

Andriy Kobalia: Let’s turn to the political dimension of this question. I know that some members of the Svoboda party made antisemitic declarations. Tyahnybok’s speech from many years ago springs to mind…

Serhiy Hirik: That was in 2003, when [Oleh] Tyahnybok gave a speech on Mount Yavoryna. At the time, he was a member of the Our Ukraine [parliamentary] faction, and he was expelled for this. This led to the restriction on exploiting such ideas, at least in public statements. Afterwards, he met with the Israeli ambassador, and his present attitude is not known. In reality, this is not so important because at the present time he is out of public politics.

Andriy Kobalia: So now we can say that the Svoboda party does not have antisemitic declarations in its program?

Serhiy Hirik: They weren’t in the Svoboda program and I think there is really little to say about the public statements of the party leaders because the Svoboda party is not very publicly active and is not represented in Parliament. Other parties are more interesting.

Andriy Kobalia: Even though parties may not be in Parliament I think they are worth noting. If we are talking about antisemitism and politics, what parties in Ukraine should we note? Svoboda may not be relevant but perhaps there are other parties manifesting antisemitism?

Serhiy Hirik: Another party is more interesting. It is still too early to say what the ideology of the newly formed National Corps party, which was created on the basis of Azov Battalion, will be on the official and unofficial levels. But manifestations of right-radical political antisemitism, the almost pogromist propaganda that was conducted earlier by the organization Patriot of Ukraine, compel one to give serious thought to the niche which this political force will be occupying and what it will be doing. Most likely, it will have two dimensions of propaganda: public and internal. It would be very interesting to take a look at the materials that they are using during workshops for their activists. I would guess that there may be overt expressions of antisemitic and other xenophobic propaganda, especially against the LGBT movement, as well as propaganda targeting immigrants from Africa. In the propaganda of Patriot of Ukraine ca. 2009–2010, we see clearly these two elements alongside antisemitism.

Andriy Kobalia: Recently my colleagues from Hromadske Radio invited Oleksandr Alferov, a member of this party’s higher political council, for a conversation. The guest’s reply to a question about the party’s future policies and social nationalism was a bit vague. You are right in mentioning there will be two aspects where publicly stated positions are not all that clear, and internal material where…

Serhiy Hirik: Yes. But internal material is what is striking. When we look at Svoboda, we saw moderate statements from Tyahnybok, but Russophobic statements from Mrs. [Iryna] Farion and the reprinting of Nazi propaganda and Goebbels’s articles in the collection Vatra and Vatra v. 2.0. Even propaganda material for internal party purposes can be made public.

Andriy Kobalia: Let’s turn to mass media, which is very important as it has an influence on society. You mentioned publications and articles. I know that between 2001 and 2008 the level of antisemitic statements in the mass media decreased. How can this be explained? I would also like to mention the controversy around the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management. [MAUP]

Serhiy Hirik: It’s best to talk to Vakhtang Kipiani, as he collected nearly all the fundamental publications of MAUP. But first of all the upper limit is not 2008 but 2007 because MAUP suddenly stopped publishing antisemitic materials in 2007. This is connected with a certain financial injection into MAUP and the creation of several research centers on the premises of that university. In the European press at the time this university began to be called the “University of Hatred.” The financial injection is connected with one of the countries in the Middle East. This is not completely documented and cannot be definitively confirmed although there is information on exactly which country it may be. MAUP then organized several “scholarly” conferences on “Zionism as the greatest threat to civilization” and so on, and conferred an honorary doctorate on David Duke, the former head of the Ku Klux Klan, who is presently engaged mostly in conducting anti-Jewish rather than anti-black propaganda. In addition to its own periodicals Personal and Personal +, it founded a network of regional publications. Materials specifically targeting the State of Israel were mostly disseminated within the framework of this campaign, but often they were interspersed with texts denying the Holocaust or with a description of the Beilis affair, which stated that Andrii Yushchynsky was murdered, if not by Beilis, then by another Jew. In addition to the commissioned anti-Zionist propaganda, we see there other examples of widely disseminated antisemitic material.

Andriy Kobalia: We were speaking with the historian Serhiy Hirik about contemporary antisemitism in Ukraine. This has been the program Encounters, which is made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Andriy Kobalia has been at the microphone. You have been listening to Hromadske Radio. Listen. Think.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This program is created with the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.