“For a massacre, I usually wore jeans”: A review of ‘Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction’ by Adam Jones

“A genocide begins with the killing of one man—not for what he has done, but because of who he is,” declared the diplomat and former United Nations General-Secretary Kofi Annan. [1] This apt statement requires some clarification, and it gives rise to a number of research questions. First and foremost, there are cases where an identity—political, social, economic, or religious—may be imposed on a person or a group of people by the organizers of a genocide. For example, people were killed in Indonesia only because they were suspected of having links to communists. Is it easy to recognize genocide in the maelstrom of violence around the world? What is the mechanism of recognizing genocide from the standpoint of international law? Can the killing of people motivated by their group affiliation always be called genocide? How do historical, sociological, anthropological, gender, and other studies of genocides figure in this?

Answers to these questions may be found in the book Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, written by Adam Jones, a Canadian specialist in genocide research, a professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia Okanagan in Kelowna, and a photojournalist. The Ukrainian translation of his book was recently published by Dukh i Litera, a publishing house that specializes in intellectual books. The Ukrainian publication is based on the third revised and expanded edition of Jones’s book. It is important for the author to continually reconceptualize topics and update historiography and scholarly discussions in his texts. Thus, the Ukrainian translation of the third and latest edition of his book offers readers an analysis of the latest research and sociopolitical discussions and surveys in the multidisciplinary field of Genocide Studies.

In terms of thematic coverage, this book is the most comprehensive guide to questions of genocide. It is divided into four substantial sections that together form sixteen chapters and a separate segment entitled “Photo Essay.” The first part of the book seeks to acquaint the reader with Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide,” the legal approach to recognizing genocide based on Lemkin’s proposals, as well as sundry variations of research definitions of this category. Jones warns us that this part of the book is complex, and advises readers “to put on their safety belts.” [2]. Despite the relevance of the author’s caveat (deep immersion in the development of Genocide Studies does not instantly offer an opportunity to understand the “system of coordinates” of this discipline), he does not let his readers flounder. Jones constantly seeks to maintain a comprehensible narrative line. His circumspect advice helps readers to avoid floundering amidst the array of definitions of the concept of “genocide.” Thanks precisely to this, the rich and complex theoretical section of the book (which outlines a number of aspects connected both with the process of forming the legal definition of genocide and its subsequent application, conflicting cases, and scholarly opinion) will become a firm foundation for readers to engage in further research.

In the first part of his book, Jones outlines the general panorama of the evolution of Genocide Studies and highlights the basic historiographic vectors and topics to which young researchers should pay attention. This is intended to provide readers with an understanding of the context in which the interdisciplinary research branch of Genocide Studies emerged.

The next section of the book is devoted to accounts of individual genocides. Jones analyzes seven cases, beginning with the killing of aboriginal peoples and ending with the genocides in the African Great Lakes region. Each chapter is replete with an array of multi-directional historiographic materials. The author offers the most complete picture of interpretations of each genocide, revealing the results of the most current research. Particularly valuable is the fact that Jones examines not only the research positions with which he is in accord but also those which he critiques in a reasoned manner. Readers, therefore, gain an opportunity to acquaint themselves with the entire spectrum of research approaches to the analysis of each genocide. Second, this approach demonstrates the dynamics of unfolding discussions and dispels the idea that there is consensus among researchers about the treatment of various genocides. Third, the author’s discussive approach is intended to encourage readers to think for themselves and to acquaint themselves further with the literature recommended at the end of every chapter. Jones also draws attention to promising aspects of further research.

Since Genocide Studies lie within the field of interdisciplinary and comparative research, Jones makes use of the work done by historians and political scientists, as well as research that has been done in other social sciences such as Psychology, Sociology, Social Psychology, and Anthropology. He also brings to light every individual case of mass violence by comparing it to other genocides through examples and contexts. The importance of the comparative approach lies in the fact that it allows researchers to apply theoretical models used by researchers from other social sciences.

The extremely representative source base of the book also deserves attention. Jones cites official sources (statements, reports of international organizations, documents issued by government bodies, etc.) and ego-documents (reminiscences, memoirs, diaries, letters). He analyzes periodical publications and uses a considerable number of visual sources, especially photographs and posters. The researcher thus aims to present the experience (vision/position/perspective) of various participants of the genocidal process: organizers and executors of killings (perpetrators), survivors, rescuers, and bystanders. This approach contributes to an understanding of genocide as a complex, multifaceted process that is not a constant but which unfolds according to its own internal dynamics.

The author also took care to maintain balance in presenting various contexts. The chapter about the Holocaust is devoted both to the events of the Second World War (which formed the background to the unfolding of the genocide) and to the context and conditions of the implementation of the “Holocaust by bullets” (the systematic killing of Jews by shooting in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union), the mass killings of Jews in gas chambers and labor camps (by exhaustion stemming from slave labor), etc. [3]. Jones also highlights the fate of other groups of victims who suffered as a result of the policies introduced by the Nazi regime: Roma, people with disabilities, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others. He takes into account the subjective experiences of individuals. Numerous inserts, entitled repeatedly “The story of one woman” and “The story of one man,” are intended to present a more complex palette of tragic events and to remind readers about important research optics.

The third section of the book covers the fundamental approaches to Genocide Studies, as proposed by social sciences. Jones identifies four key psychological factors that influence the behavior of organizers and participants of genocide: narcissism, fear, greed, and humiliation [4]. The author analyzes these motivations through the prism of the individual experience of odious dictators and politicians (Adolf Hitler, Mao Tse-tung, Joseph Stalin, Slobodan Milošević, and others). He also addresses the study of the collective experiences of different groups. Finally, Jones concludes that these four interconnected factors determine the behavior not only of organizers of genocides but of perpetrators as well.

The author reveals the special contributions of various social sciences to the study of mass violence (for example, Sociology, Anthropology, Gender Studies). He also constructs his narrative in such a manner that readers can understand how each of these sciences functions, from which angle it “looks” at Genocide Studies, and how this focus is important for understanding this phenomenon.

The last section of the book examines questions of international legal regulation as well as contradictory memories of genocide and reconciliation, which countries and societies face after a crime has been committed. Here Jones points to “certain traces and favorable conditions” that “may serve as red flags” for recognizing an approaching genocide. [5]. He outlines the history and main strategies of humanitarian interventions for the purpose of preventing crimes. This is a broad field of activities not only for researchers but also international political, military, and humanitarian bodies whose goal is to counteract genocides.

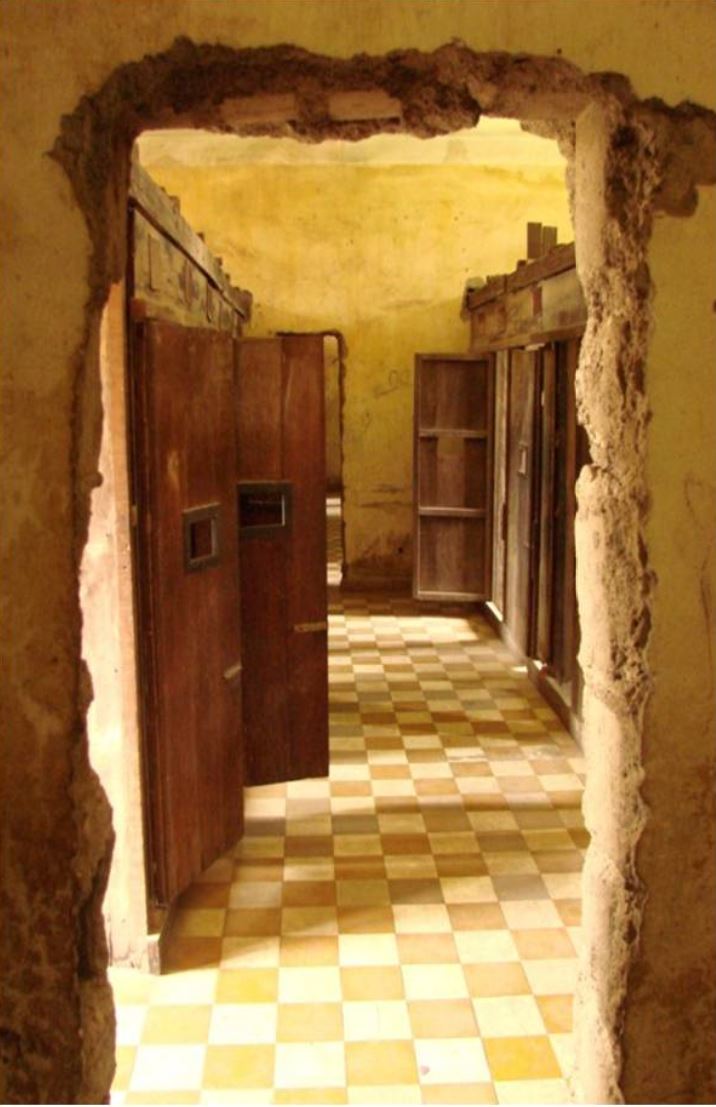

The photographs featured in the book deserve separate mention. Jones is a photojournalist, who has collected an immense archive containing more than seventeen thousand images. Quite a few illustrations are used in the Ukrainian edition. There are photographs from the author’s personal archive, which he took in places where genocides and mass killings took place. This rich visual material enhances the unique nature of the publication. In the chapter entitled “Photo Essays” Jones poses a question about “how to present genocide in photographs in order to avoid clichés and the depersonalized images of corpses and piles of skulls.” [6]. In this section, the author demonstrates through photographs and reflections about them that it is important to focus on presenting the multi-vector experiences of societies that have lived through genocides.

The researcher focuses on landscapes (which “remember” genocide), artifacts of the genocidal process, buildings, and, of course, people. He has accumulated considerable experience in working with photo presentations of genocide. His work is a rare combination of the activities of a genocide researcher, photojournalist, and professor. At the end of this chapter Jones provides a list of key works devoted to the topic of representations of genocide in photography.

It is worth indicating the features of the Ukrainian-language edition. The title in Ukrainian, Genocide: An Introduction to Global History, is not a literal translation from the English. Given the materials presented in this book, the chosen title seems to reflect more accurately a “type of historical analysis in which phenomena, events, and processes are examined in global contexts [7], and the work is written according to the canons of global history.

Ihor Vynokurov and Olena Stiazhkina, specialists in twentieth-century Ukrainian history, are the scholarly editors of the Ukrainian translation. They took care to ensure that the text would be comprehensible to Ukrainian readers. Thus, the book contains footnotes, mostly explanatory in nature. Sifting through the immense historiographic corpus used by the author, the editors identified publications that have already been translated into Ukrainian.

The author also took pains with the book’s structure and ensured that the material is presented in an accessible manner. In particular, Jones identifies the affiliations and positions of the individuals mentioned in the book, lists definitions for the majority of terms, and, at the start of every chapter, indicates the algorithm according to which the material was presented. To ensure ease of comprehension, subheadings appear in the form of questions, such as: Why should genocide be studied? What is destroyed during a genocide? Can genocide ever be justified? When is military intervention justified?

Finally, it is worthwhile shedding some light on the following question: What is the author’s research position on topics connected with Ukrainian history, specifically the Holodomor and, in the broader context, with the crimes of the communist regime as well as the genocide against the Jews, Roma, and other victims of the Nazi regime? Perhaps, however, it would be better to omit this intentionally and end this review with an invitation to readers to begin familiarizing themselves with one of the most comprehensive books about “mankind’s darkest times.”

This material was prepared specially for the Web site of Ukraїna Moderna. It is published here for the first time. Reproducing the text (partially or in its entirety) requires permission from the author or the editorial office of the Ukraїna Moderna Web site. ©Tetiana Borodina.

The article uses illustrations supplied by the author.

Tetiana Borodina is a post-graduate student of the Doctoral Program at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and a scholarly associate of the Center for Studies of the History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Center, Kyiv). Her academic interests include the history of the Holocaust, the history of the Third Reich, Genocide Studies, and Ukrainian-Jewish relations in the twentieth century. She is the co-compiler (together with Natalia Ryndiuk) of a textbook for high school students entitled Storinky ievreis′koї istoriї Ukraїny [Pages of Ukraine’s Jewish History], and the scholarly editor of Ukrainian translations of studies on the history of the Holocaust.

Tetiana Borodina is a post-graduate student of the Doctoral Program at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and a scholarly associate of the Center for Studies of the History and Culture of East European Jewry (Judaica Center, Kyiv). Her academic interests include the history of the Holocaust, the history of the Third Reich, Genocide Studies, and Ukrainian-Jewish relations in the twentieth century. She is the co-compiler (together with Natalia Ryndiuk) of a textbook for high school students entitled Storinky ievreis′koї istoriї Ukraїny [Pages of Ukraine’s Jewish History], and the scholarly editor of Ukrainian translations of studies on the history of the Holocaust.

[2] Ibid., 27.

[3] The “Holocaust by bullets” is the term used to denote the mass killings of mostly Jews, who were shot in the German-occupied territories of the Soviet Union. Two clarifications concerning the use of this term must be made. First, other victims of the Nazi regime could have been shot together with Jews; second, it should be understood that the term “Holocaust by bullets” focuses attention on the killings of Jews by shooting near the places where they were born or lived. However, this does not mean that the shootings in the above-mentioned territories were the only method that the Nazis used to dispatch their victims.

[4] Dzhons, Henotsyd, 411.

[5] Ibid., 594.

[6] Ibid., “Photo-Essay,” 1.

[7] Sebastian Konrad [Conrad], Chto takoe global′naia istoriia, trans. from the English A. Stepanov with an Introduction by A. Semenov (Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, 2018), 22.

The accuracy of the facts and quotations cited in this article is the responsibility of the authors of the texts.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.