Ivan Franko and his Jews: childhood, student years, politics

I will try to define Franko’s attitude to Jews, which ranges from sincere Judeophilism to radical Judeophobia. This ambiguity in the interpretation of his views intensified after the fall of the communist regime in Ukraine. Since the disappearance of censorship, the majority of Franko’s texts in which his favorable attitude toward Jews and Zionism come through clearly have been published with commentaries.

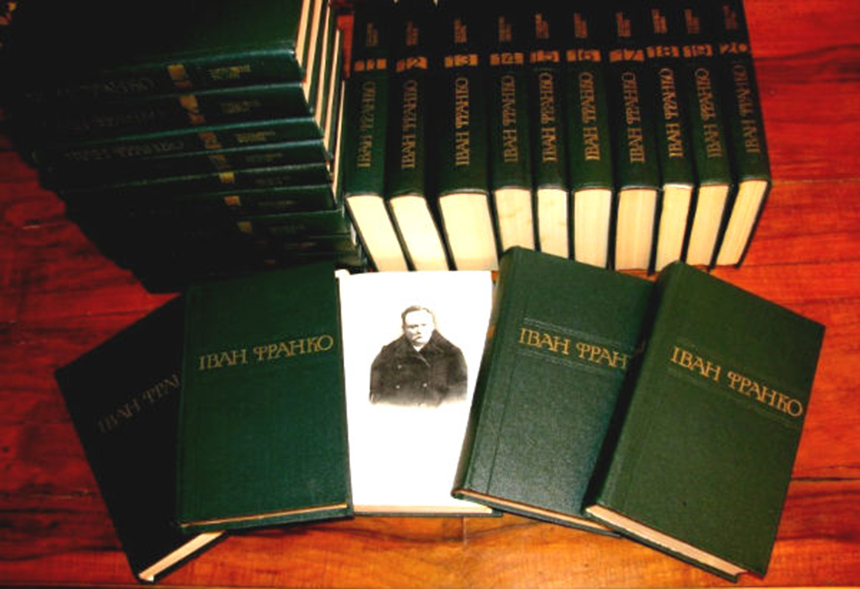

In Ukrainian intellectual history, there is not a single other author who devoted more attention to Jewish subjects than Ivan Franko. The richness of Jewish themes in his work contrasts sharply with the relatively small number of studies on this topic.

The lengthy silence surrounding this problem reflects the general trend of the tacit prohibition against researching Jewish subjects, which reigned in Soviet scholarship. In Soviet Ukraine, this trend acquired extreme manifestations, compared at least to the Baltic republics, where Jewish themes, albeit very limited, were present in local academic discourses.

In the specific case of Franko’s legacy, this led to the removal from collections of his works of poems, stories, and essays on Jewish themes.

For example, let’s examine the secret memorandum drafted by Glavlit (the main censorship committee) of the Ukrainian SSR, which was sent to Leonid Melnikov, secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, on 12 March 1953, entitled “On the Harmful Practices of the Institute of Ukrainian Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.”

This note, among other things, proposed to stop the publication of an edition of Franko’s works in which his poem Moses was slated to appear, because “the poem praises the ‘promised land’ of the Jewish people of Palestine, the Jews’ sadness for Palestine, which to them is their native home, etc.” A list of Franko’s works on Jewish subjects that were never published in the Soviet Union can be found in Zinoviia Franko, “I. Franko’s 50-volume Collected Works in Today’s Evaluation” (Suchasnist, no. 10, 1989).

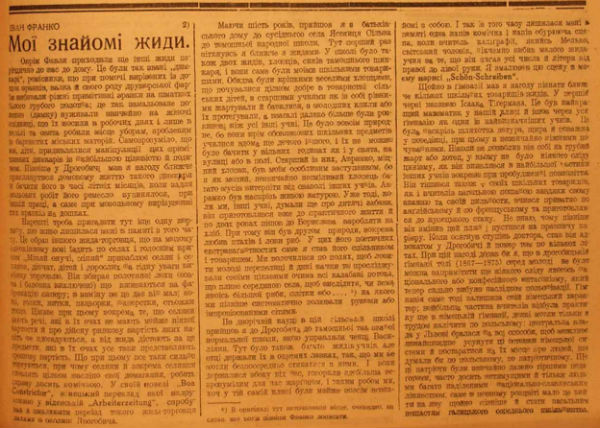

Ukrainian humanities studies outside the USSR could not compensate for this defect. In 1939 achievements in this area were limited to the publication of several previously unknown articles by Franko and reminiscences about him (for example, Ivan Franko, "My Jewish Acquaintances,” Dilo, 28 May 1936, № 117), and after 1945, already in the emigration, to a handful of somewhat apologetic articles on Jewish issues, which are not devoid of interesting observations. The most interesting among them was Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky’s article, “The Problem of Ukrainian-Jewish Relations in Ukrainian Political Thought of the XIX Century,” which devotes a considerable amount of space to Franko.

Passing references to Franko in relation to the Jews can be found here and there in the publications of non-Ukrainian authors in the West. These studies are distinguished from those produced by Ukrainian diaspora scholars by the fact that they are all cursory mentions (mainly in footnotes), and Franko is almost always presented as an antisemite. The lone exception is the article by Asher Wilcher, “Ivan Franko and Theodor Herzl: To the Genesis of Franko’s ‘Moisei,’” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, no. 6 (1982).

The notion of Franko’s antisemitism is much more pronounced in journalism. Two articles deserve mention. The first is an unsigned article entitled “Ivan Franko and the Jewish Question,” published in Krakivski visti during the Nazi occupation (28 May 1943, № 112), on the eve of the final destruction of the Galician Jews. The article was custom-written in nature, and all its fervor is aimed at refuting the prevalent image of Franko as a philosemite. John-Paul Himka, who had access to the archives of Krakivski visti, managed to identify the author of the article but revealed his name only after he died in 2001: Anatol Kurdydyk.

The second article was published in the wake of Franko’s centenary in Forverts [The Forward], a magazine put out by American progressive Jews. Its author, offering the example of Franko’s stories from the Boryslav cycle, which were introduced into school curricula, sought to prove that the Soviet government was purposefully spreading antisemitism among young people.

Franko was called a haidamaka and genuine heir of Khmelnytsky and [Ivan] Gonta, his works presaging pogroms and the destruction of the Jews,” “a vile pogromist,” and he was tarred with the same brush as the haidamaka Nikita Khrushchev, in whose veins seethes the unclean blood of Bohdan Khmelnytsky.”

Each of these two articles reflects an extreme point in the broad spectrum of assessments of Franko’s attitude toward the Jews—from sincere Judeophilism to radical Judeophobia. This ambiguity in the interpretation of his views intensified after the fall of the communist regime in Ukraine. Since the disappearance of censorship, the majority of Franko’s texts in which his favorable attitude toward Jews and Zionism come through clearly have been published with commentaries.

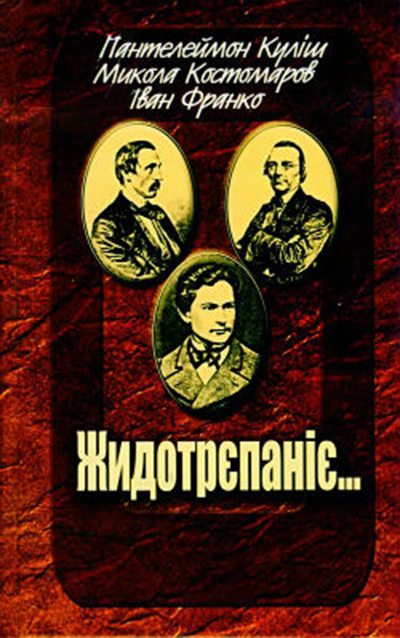

On the other hand, the theme of “Franko as an antisemite” got a new lease on life. In works exploring the “harmfulness of Jews” in Ukraine, one can encounter Franko being cited as a classic exploring this theme. Take, for example, Ivan Franko, Zur Judenfrage (On the Jewish Question), published in 2002 in Kyiv; Panteleimon Kulish, Mykola Kostomarov, and Ivan Franko, Zhidotrepanie (Jew-Beating, Kyiv, 2005); Vasyl Yaremenko, Ievrei v Ukraini siohodni: Realnist bez mifiv [The Jews in Ukraine Today: Reality without Myths] (Kyiv, 2003). All three books were published by the Interregional Academy of Personnel Management (MAUP), known for its active efforts to spread antisemitism in Ukraine in those years.

Both views are constructed out of a selective reading of Franko’s literary heritage. Thanks precisely to these considerations, the compilers of an additional volume of Franko’s “censored” works did not include his poems about Shvyndeles Parkhenblyt and his articles “Pytannia zhydivske” [The Jewish Question], “Moses Mendelssohn, the Jewish Reformer,” etc., the difference being that in the latter case, the articles are also poorly disguised political manipulations.

The question of whether Franko was an antisemite is an important one, but it is merely one part of the topic of “Franko and the Jews.” It is no less important to show how, in his attitude to the Jews, he was constructing the framework of an imagined community that he called his “people.”

Franko’s life coincided with the period when the Jews were undergoing a powerful transformation that was erasing the old identification of Jews with Judaism and blurring the meaning of Jewish identity. In these new conditions, a “Jew” ceased to be only self-identified. He was also an identity that was imposed from the outside on significant groups of people, mostly assimilated Jews. The attitude to the Jewish question determined the boundaries of their own identity. Therefore, discussions about “who is a Jew”— and especially who is a “good Jew”—spoke volumes not only about the Jews but also about the discussants themselves.

Still-extant folklore collections reveal that the mass consciousness of Galician Ruthenians consisted of rich material for constructing distance concerning the Jews. The proverbs on Jewish themes that Franko recorded and published in a separate volume of Etnohrafichnyi zbirnyk [Ethnographic Collection] are proof of this.

This enumeration alone is enough to grasp the unvanquishable distance between local Christians and Jews. In the eyes of the former, the latter look practically like a caste—a caste of untouchables, at that. However, Jews are a special caste because they rose above the Christians: They are extraordinarily cunning and crooked, they exploit the peasants mercilessly.

The Jew is also absolutely “alien” to the peasant because of his religion, whose calling is to torment and even kill Christians. Jews will have no salvation in the other world, but even in this one, they do not deserve Christian sympathy and help. Thus, in local proverbs Christians who serve and help Jews get what’s coming to them.

The negative image of the Jew was predominant, but it was not the only one. A rather large group of sayings depicted Jews quite neutrally (albeit in a mocking fashion on occasion). Some of them were echoes of superstitions: To see a Jew in one’s dreams or when he is crossing the road is a good sign.

Some sayings convey the view that a Christian can sometimes be worse than a Jew, as well as respect for Jews for being firm in their faith. Two proverbs stand quite apart as a statement of tolerance: “It’s bad with and without the Jew,” and “As not every Jew is lousy, so too not every peasant is a pig” (the latter saying is a response to a widespread Jewish, anti-peasant stereotype). The lack of relevant research makes it impossible to analyze anti-Christian stereotypes among Eastern European Jews.

Ivan Franko collected a considerable number of Jewish-themed proverbs in Nahuievychi and the neighboring village of Yasenytsia Silna. Familiarity with local attitudes on the basis of such sayings suggests that from an early age Franko was more likely to become an antisemite than a semitophile. However, his childhood was relatively free from these stereotypes. One of his earliest memories about Jews is of his mother bringing a few Jewish cakes that a female tavern-keeper in Nahuievychi had given to her:

“Children!” my mother shouted to me and my brothers and sister.” Look what Sarah gave me for you.” She broke apart the dry pancakes and gave it to the children: “Eat, this is Jewish paska [Passover bread]. True, people say that it contains the blood of Christian children, but this is nonsense.”

“This was the first more memorable impression of Jewry that I have left from my childhood,” Franko recalled. "It was also the first time I ever heard about the blood tale. Mother stated her opinion of it so calmly and decisively that we only gaped in surprise, without the usual horror into which, as it happens, much older and more educated people fall so often during conversations about this. At the same time, mother gave the best proof that she did not believe in the blood fable, by eating, together with us, the pieces of bread she had brought.

Franko believed that this “blood fable” in Ruthenian-Ukrainian villages was well known, but it did not elicit in the peasants “either deeper emotion or grotesque hatred.” We find contradictory evidence in the memoirs of Franko’s peer, Rev. Mykhailo Zubrytsky. He recalled his fear when, as a small boy, he first saw a lot of Jews in Peremyshl; his father had taken him to a local tavern when they were traveling to a relative from a distant village. The little boy was told that “Jews abduct small Christian children, place them inside barrels packed inside with nails, the barrel is rolled, and that’s how they let the children’s blood flow, in order to mix it with their Passover bread.” He fled the tavern in fright, and his father had to catch up to him.

Franko’s family lived on the outskirts of a village, where there were no Jews and no tavern. His points of contact with the Jewish world were few and far between. From time to time, poor Jews came singly to this part of the village, offering their humble wares and tradesmen services.

Franko’s first experience of coexisting with Jews was when he was studying in Yasenytsia Silna. Among the students were two sons of a local tavern keeper. One of them, the precocious Avramko, defended the timid Franko from the ridicule of the older pupils and became his friend.

Franko’s real acquaintance with the world of Galician Jews began when he was sent to study in Drohobych. The year before, in 1863, there was a pogrom that was instigated by patriotic Polish high school students.

During his years of study, Franko witnessed regular fights between older pupils and local Jews. According to him, there was no violence in the relations between Christian and Jewish pupils either in the Basilian school or in the gymnasium. True, the Basilian fathers made Jewish children sit on separate benches and did not allow them to associate with Christian pupils. In the gymnasium, however, no such segregation existed. At the time, there was not a trace of the national or confessional conflict that subsequently erupted among high school and university students in Galicia. Its sole manifestation at the time was Polish-Ukrainian debates about history and literature. Jewish students were kept away from these discussions, but some of them were recorded in the Ruthenian language or literature.

The memoirs of Franko’s contemporary, Maurycy Gottlieb, who died prematurely (1856–1879), paint a different picture. He claims that he and other Jewish children suffered greatly at the hands of Christian pupils. The dissimilarity between the two reminiscences does not necessarily mean that one of the two authors is untruthful. The reason may be the difference between Franko’s and Gottlieb’s understanding of what is regarded as an insult and a conflict.

By the way, in neither Franko’s nor Gottlieb’s reminiscences can we find any detailed mention of the other. Most likely, they kept each other at arms’ length. Franko’s closest friend was Gottlieb’s relative, Isaac Tigerman, who showed outstanding mathematical talent and eventually chose a career as a lawyer, but also died young in Drohobych.

Franko and the Tigerman family were bound by a lengthy friendship. Isaac’s father corresponded with Franko for a long time, even after he moved to Vienna, especially since he had gotten into the habit of visiting the Ukrainian student society “Sich” and became, as he jokingly admitted to Franko, a “strong Ruthenian.” Isaac’s mother had immense respect for Franko, and long after he had left Drohobych, she told local high school students that “there is no greater mind in all of Austria, he could have been a minister long ago, if not for socialism, into whose service he went.”

That a great distance did not exist between Jewish and Christian students is attested by the fact that when Franko worked as a tutor, most of his contracts came from Jewish families in Drohobych.

From his acquaintance with the family life of Galician Jews, Franko the pupil reached two important conclusions. First, Jewish children were more developed than Christian ones. He explained this circumstance to himself by the fact that Jewish boys studied much more, both at school and at home. Second, in Jewish families, he was struck by the sincerity of relations between the generations and the parents’ ability to rejoice at their children’s successes, support them with a kind word and praise, sometimes even exaggerating their real successes.

Franko the pupil listened enviously to the words of praise that Shternbach the father, with tears of emotion, directed at his talented son, “because I, a poor, prematurely orphaned peasant son had no one in the world who would fuss over my progress with such great love and with at least half as much great understanding.”

Observations on the differences between the Christian and non-Christian world aroused Frank’s interest in the culture of the East, when he was already studying at the Drohobych gymnasium. Even then, he admitted, he was “drawn to the East.” The Old Testament, along with the ancient authors, made a deep impression on him. He read them in Church Slavonic, German, and Polish translations, and eventually translated many of the verses from the Book of Job and several chapters from the Book of Isaiah.

The father of his school friend, Limbach, after reading Franko’s translations of the prophets, told him: “What are you looking for there with respect to the Jews? Are you capable of understanding their feelings and conveying them properly? And even if you were capable, ask yourself: How is this useful? Who needs this? Does anyone care now about what those people were interested in thousands of years ago?”

Limbach often visited Franko, borrowing volumes of Western literature from him. Through him, Franko became acquainted with the world of assimilated Jews, quite a few of whom lived in Drohobych

After enrolling at Lviv University, Franko briefly lost touch with Jews. There were no Jews among the students who, together with him, registered for course in philology. They were also absent from the student societies of which Franko was a member.

The then Ruthenian-Ukrainian student environment was not free from antisemitic prejudices. The magazine Druh [Friend], even before the editorial office reversed its policy in favor of Ukrainian interests, advertised the publication of a translation of the Talmud for the popular masses, so that people would know what “the Jews think of us, into what nets they are trying devilishly to entangle every Christian.”

The resumption of Franko’s contacts with the Jewish world is connected with the beginning of his socialist activities.

The Galician Socialist Committee, formed around the newspaper Praca [Labor], set itself the goal to create a Ruthenian-Polish-Jewish workers ‘and peasants’ party. Accordingly, socialist propaganda was to be conducted in the languages of all these groups. This idea deviated markedly from the practice and ideology of most European socialist movements, rejecting the need for separate organizations and separate publications for the proletariat of “non-historical nations,” which, in the case of Galicia, were Ruthenians and Jews.

But the position adopted by the Galician Socialist Committee implicitly recognized Jews as a separate nation and placed them on the same level as other peoples. It is likely that this idea did not belong to Franko or anyone else from the editorial offices of Praca; keenly felt here was the influence of [Mykhailo] Drahomanov, who was waging “cultural wars” in the emigration with Polish and Russian Socialist Revolutionaries for the right of “non-historical nations” to their own socialist movements. But Franko was one of the most ardent of its propagandists, as evidenced, in particular, by his popular presentation of the program of the Galician socialists entitled “What Does the Galician Socialist Community Want?”

Franko applied his energies to establishing contact with the Jewish workers’ milieu. Two Jews worked in the editorial offices: the brothers Ludwik and Adolf Inlander. Franko was good friends with them, and he later described Ludwik as a “sincere friend of our nationality, a man honest through and through with a broad education.” Ludwik Inlander partially financed the publication of “Na dni” [At the Bottom], one of Franko’s most famous short stories. However, like other “progressive Jews,” the Inlander brothers were not suited to the role of propagandists among poor, unassimilated Jews.

In a letter to Mykhailo Pavlyk dated 5 June 1880, Adolf Inlander admitted: “There are no progressive Jews who could realize a project to create a separate Jewish current among working Jews. The ones that exist cannot be called Jews because they have no relation to the mass of Jews, but in fact, to the Jewish proletariat, and even with it they could not reach an understanding because they do not know either the language or customs.”

Paradoxically, it was Ivan Franko who, thanks to his good knowledge of Yiddish, applied the greatest efforts to ensure the “Jewish direction” in the activities of the Galician socialists, especially in Boryslav. During his forced stay in the vicinity of Drohobych in 1881–1883, Franko recorded a song that was circulating among poor, local Jews (kaptsany), and he interpreted it as a sign of the emergence of class feeling among the Jewish proletariat.

Examples of Ukrainian-Polish-Jewish cooperation on socialist grounds looked like an anomaly against the general background of social and political life in Galicia. Antisemitic sentiments affected, in particular, all orientations within the Ruthenian-Ukrainian camp.

Rev. Stepan Kachala, leader of the populists, wrote in his brochure, Polityka rusyniv [The Ruthenians’ Politics] (1873), that in relations with the Jews, the issue is not so much the protection of their rights as the very existence of the Ukrainian people—so quickly are they stripped of their property because of the Jews’ “treacherous actions.”

The Russophile priest Ivan Naumovych linked the degree of demoralization afflicting the Ruthenian- Ukrainian peasantry directly with Jewish influences. It exists least of all, he wrote, among the Lemkos, the most westerly Ruthenian ethnic group, where there were very few Jews. There, little is heard about a thief or swindler, and considerably less drunkenness, which grinds the “healthy body of Galician Rus′. Meanwhile, [Naumovych wrote] the most demoralized is the Hutsul region, which the Ruthenians once called their “Palestine, flowing with milk and honey,” but now it is truly a “Jewish Palestine.”

This observation was shared by the socialist Mykhailo Pavlyk, who was from the Hutsul region. In 1876 he wrote: “Trouble with the Jews may come soon to Galicia: I see and know this from what our people say.”

The spread of antisemitic sentiment was also noted by outside observers. After visiting Galicia, an anonymous Russian traveler wrote in his travel notes that, although religious intolerance between the local Christian and Jewish populations was unnoticeable, both Poles and Ruthenians did not like Jews. The Ruthenian’s dislike was deeper and expressed at times through direct violence because in general Polish peasants were less likely to encounter Jews than Ruthenian peasants. But the roots of antisemitism were the same—economic exploitation:

“All the well-known observers of Hutsul life, especially parish priests, unanimously claim that the Jews brought terrible demoralization to the Hutsul environment and destroy their well-being. In fact, during some ten years in Hutsul settlements, especially, for example, in Zhabie, Jews have so proliferated that they make up about 15 percent of the total urban population. “Where there is a Jew,” many competent people told me, “there drunkenness, debauchery, and extreme poverty appear among the Hutsuls and Boikos!” (Cited in “Galichina i Rusiny: Iz dorozhnykh zametok i nabliudenii,” Vestnik Evropy, September 1886, p. 126.)

During the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a belief among the Galician peasants that the day of reckoning was approaching when all Jews would be killed. The peasants had hopes for the new arrival of the army of the Russian tsar, who was supposedly going to give the peasants land belonging to Polish lords and allow the Jews to be beaten. Mykhailo Drahomanov, after his visit to Galicia in 1875, recalled the words of a Hutsul about the future “war against the Jews,” which “may God and St. Nicholas grant.”

In any case, as an anonymous writer from Lviv wrote in 1884, antisemitism is a universal feeling, it is shared by everyone, from the poorest man to the heir to the throne, and he quoted a recent statement of the latter, Archduke Rudolf, which concerned the Jews of northern Hungary (today: the Ukrainian region of Transcarpathia): “Living amidst the simple but honest Ruthenian people, they manage according to their own will and their convenience, and in exploiting them at every turn and going to the authorities over them, they lead them to perdition, and before they plunge them there, they order them to serve them.”

The author of this correspondence advised the Jews in Galicia “to sit quietly and be contented that everyone is still opposing them in a legal fashion, having even more examples that in other lands there are attempts to get rid of them in a completely different way, like, for example, in Russia, Germany, or in Hungary, all the more so as here, in Galicia, the glass is already overfilled.”

Of course, all these statements should be accepted with great reservation, as they testify to the concepts prevalent among the Christian population rather than to the real situation.

Compare them with the observation made by the Austrian ethnographer R. F. Kaindl, who lived for a long time among the Hutsuls. He refers, in particular, to the widespread practice of childless peasants adopting an outsider and being willing to hand over their property on condition that he take care of them until death. Jews were often the objects of such adoptions because they were considered trustworthy. Among Hutsuls, it was not considered sinful to have sexual relations with Jews. The Hutsuls showed much greater intolerance toward avaricious priests and evangelists (the latter were disliked for not observing fasts), and most conflicts were between neighbors, because, as a rule, neighbors were not chosen as godparents because it was believed that disputes between a family and the godparents were a sin.

It is important to note, however, that in popularizing Ruthenian-Jewish solidarity, Franko was out of step with prevailing sentiments. Thus, it comes as no surprise that he and his friends were called “Jewish hirelings, Jewish servants, Jewish accomplices, and God knows what other Jewish brothers,” while Franko himself was considered to be half-Jewish.

Excerpts from the book Prorok u svoii vitchyzni: Ivan Franko i ioho spilnota [A Prophet in His Own Land: Ivan Franko and His Community] (Kyiv: Krytyka, 2006). Published with the author’s permission.

29 May 2018

Yaroslav Hrytsak

Doctor of Historical Sciences, professor of Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, lecturer at Ukrainian Catholic University, author of eleven books

Istorychna Pravda’s ‘Shalom!’ media project, which explores the Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue, is made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Istorychna Pravda

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.