Joseph Roth, the great autobiography hoaxer

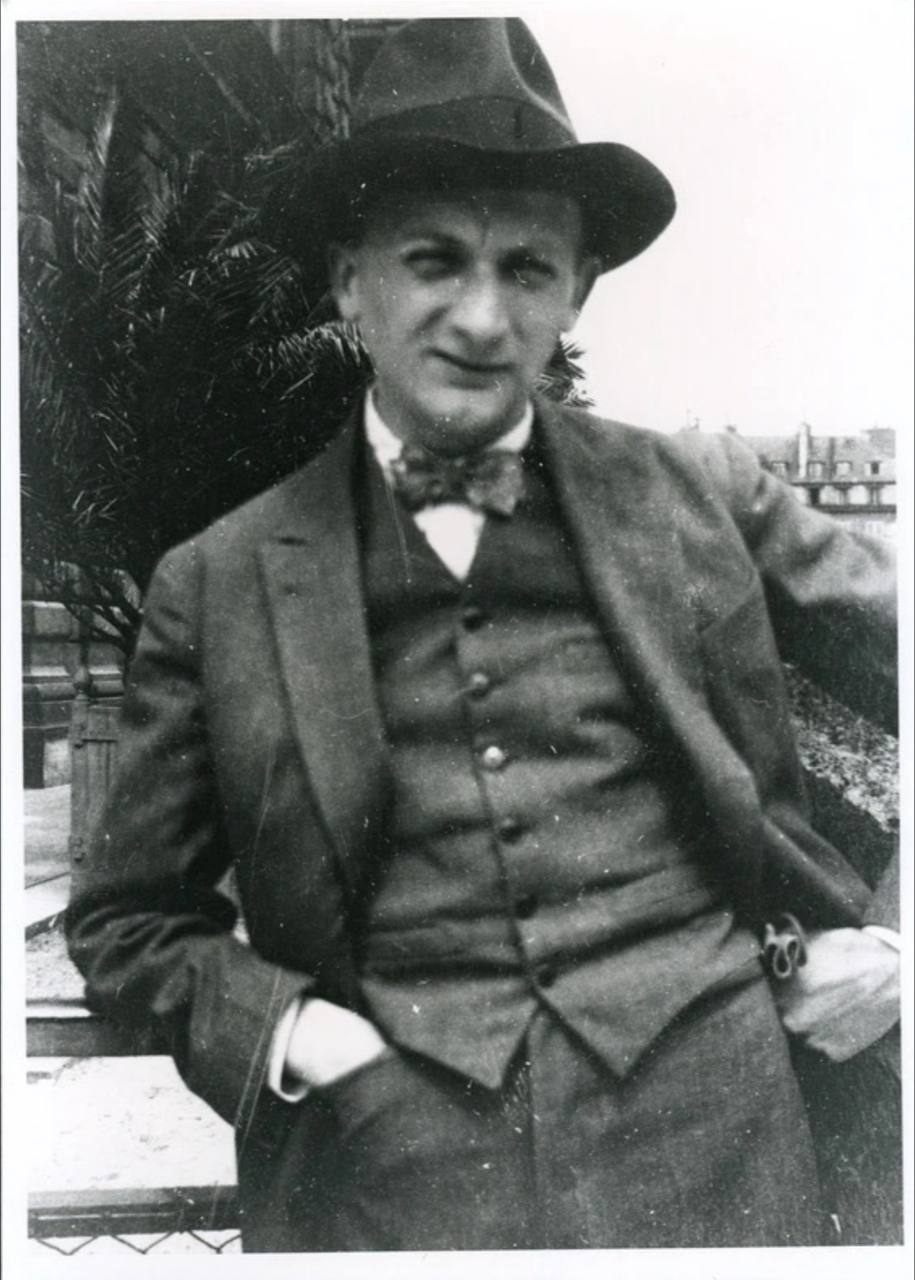

Joseph Roth, one of the most famous 20th-century German-language writers and journalists, was a Galician Jew, monarchist, socialist, cosmopolitan, hoaxer, and alcoholic. He was a successful reporter (but always short of money), hotel ambassador, and café regular. Roth was a child with a Faustian desire to know the world and an adult with a naive childish smile. His life as an artist, full of ups and downs, could readily provide a plot for a great novel.

Autobiography hoaxes

Joseph Roth produced very different, sometimes contradictory versions of his biography. He easily strung together completely unexpected details, covered his trail, and invented alternative facts. From early childhood, he used irony to great success to distance himself from reality. His sense of humor could seem somewhat peculiar. For example, when drunk, he liked to tell people that he kept his deceased mother's uterus in a special solution at home. Was it true? A metaphor? A joke? It is difficult to give an exact answer now as no evidence exists to confirm his claim. The "darkest" side of this story is that Miriam Grübel died of cervical cancer in 1922, presumably as a result of an unsuccessful operation. Before that, Roth visited her in Lviv.

"In close communication, the writer's character often seemed unbearable: in a fit of emotion, he could say many unnecessary things, cross the line, get personal, and offend the interlocutor. He was emotional, categorical, bold, self-confident, and, without doubt, talented."

Childhood and youth in Galicia

Moses Joseph Roth was born and raised in Brody (now in Lviv Oblast), which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time and the frontier of the "Western" and "Eastern" worlds. He spent the first 19 years of his life in Galicia and occasionally came later, already as a successful European journalist.

Brody appears in his work as an archetypal topos, a role model, a symbol of the borderland, a space of memory and understanding, and much more.

He grew up in the house of his grandfather, Jechiel Grübel. The future writer was raised by his mother, whom he described as a Jewish woman with a strong and sturdy Slavic physique:

She would often sing Ukrainian songs because she was very unhappy (and where I come from, it is the unfortunates who sing, not the lucky ones, as in Western countries. That's why Eastern songs are more beautiful, and anyone with a heart who listens to them will be moved to tears). (pp. 150–1)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books, 2013.

He was the only child in his family, but had many cousins. His closest contact throughout his life was Paula Grübel, the daughter of his maternal uncle Sigmund Grübel.

He never saw his father, Naum, who had gone mad before his son was born. In fact, his father's figure is the most compelling object of the writer's mystifications. In a letter to the publisher Gustav Kiepenheuer on his 50th birthday, Roth chose an interesting way of congratulating him and, instead of the usual etiquette-prescribed wishes, told his life story, offering an unexpected version of the family history:

She had no money and no husband, because my father, who turned up one day, and whisked her off to the West with him — probably with the sole purpose of siring me — left her in Katowice, and disappeared, never to be seen again. He must have been a strange man, an Austrian scallywag, a drinker and a spendthrift. He died insane when I was sixteen. (p. 151)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books, 2013.

Roth offered a dozen more options of who his father was, including, curiously, a Polish count, an Austrian official, a wealthy manufacturer, and a Jewish government official.

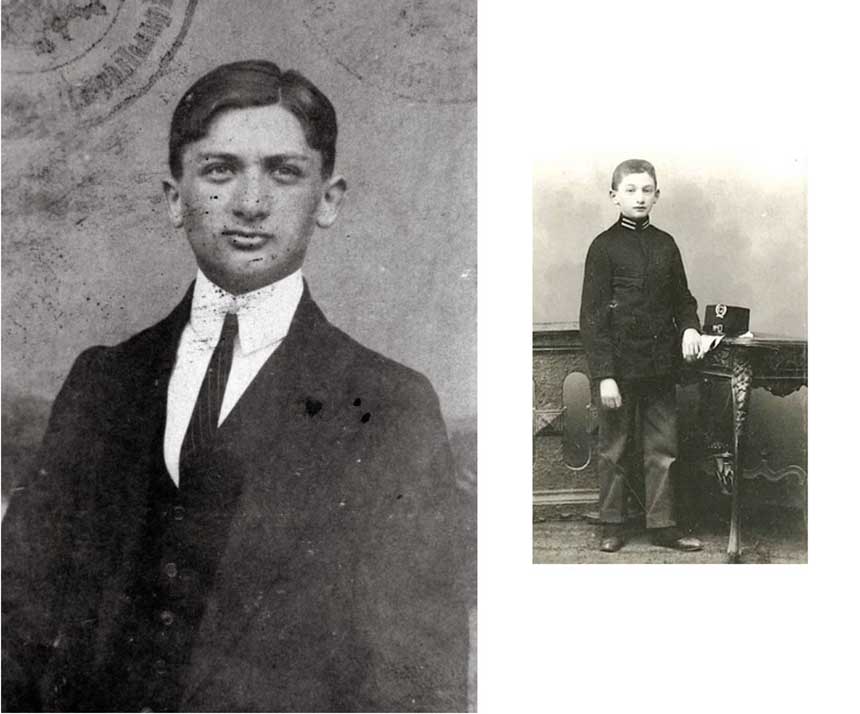

Roth's childhood was not exactly poor: his mother paid for trips to a photo studio, fashionable clothes, and individual violin lessons. She was able to provide her son with a decent education. The future writer attended the Baron Hirsch elementary school and later studied at the Imperial and Royal Gymnasium (now the Ivan Trush Brody Gymnasium). At the turn of the century, this was a favorable environment for the coexistence and complementarity of the different cultures of multiethnic Galicia. From an early age, Roth had a good command of German and Yiddish and understood Polish and Ukrainian.

Student years: an Austrian count or an eastern Jew?

On his 18th birthday, 2 September 1912, the high-school student Joseph Roth wrote a short letter to his cousins, thanking them for their warm greetings and describing his plans for the near future:

This last year will soon be over, and after my final exams, all the trials and tribulations of school will be behind me, and I will go on to the great school of life. Let's hope I earn equally good grades at that institution. (p. 7)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books, 2013.

Full of determination and optimism, he enrolled in the Philology Department of Lviv University, but the euphoria of student life quickly evaporated, and he discontinued his studies a year later. In the first decades of the 20th century, the university was a center of Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish confrontation, but Roth showed no interest in politics.

The Polish movement did not interest Roth, nor did Ukrainian ideas, and he did not attach much importance to his Jewish origin at the time.

Meanwhile, Roth was aware of his ties to the German-speaking cultural space and maintained distance and neutrality, unlike most of his high-school and university acquaintances.

One of the reasons for moving out of Lviv (Lemberg) may have been the strained relationship with his uncle, at whose place Joseph lived for the two semesters of his initial university stint, as the financial and moral pressure from Sigmund Grübel and their differing views on life kept causing conflicts.

At the end of the first year, Roth transferred to the University of Vienna to study philosophy and German literature. His memories of this period are quite contradictory, but the young man adapted quickly and seemed to have settled in society quite well. Those were the last carefree years of his life. Nevertheless, he bemoaned a constant lack of money in a letter to Kiepenheuer, which forced him to subsist on donations from his wealthy relatives and humble earnings from tutoring. Roth was diligent and ambitious.

The socio-political situation in Vienna in those years was quite unstable and fraught with danger. In the early 20th century, antisemitic sentiments were palpable in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, fueled by falsified cases of "ritual murders" and other crimes attributed to Jews. Ethnic clashes occurred at the University of Vienna even more frequently than in Lviv.

Soma Morgenstern recalled that when he and a group of other students were preparing to be beaten during another clash with nationalists, Roth, dressed as a real count, with a cane and a monocle, stood aside.

In those years, he began publishing poems in periodicals and dropped Moses from his name as a clear indicator of his ethnic background.

Roth is rightly considered one of the most devoted creators of the myth of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He constructed an idealized image of a supranational and tolerant society, which it was not. Apparently, this Austrian identity, acquired during his school years, turned out to be more attractive and desirable for him than affinity with eastern Jews.

World War I

Roth was unfit for military service due to his poor health, which perfectly suited him, a convinced pacifist. However, a year and a half before the end of the war, he suddenly decided to volunteer for the army. On 14 August 1916, Roth informed Paula Grübel of his plan to visit Baden before he was mobilized. It is known for certain that Roth was on the Eastern Front, possibly in the 21st Infantry Battalion. Some surmise he might have been a clerk at the headquarters of the 32nd Infantry Division stationed in Lviv. In 1930, he wrote to his publisher:

I volunteered for the 21st Jaegers. I didn't want to have to travel third class, to salute incessantly. I was an eager soldier, got to the line too soon, I reported for cadet school, I wanted to be an officer. I became an ensign. I stayed on the eastern front till the war ended. I was brave, strict, and ambitious. (p. 153)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books.

His accounts of this period are often contradictory. On 24 August 1917, Roth described his life as follows in a letter to Paula Grübel:

Gray filth, harboring one or two Jewish businesses. Everything's awash when it rains, and when the sun comes out it starts to stink. But the location has one great advantage: it's about 6 miles behind the lines. Reserve encampment. (p. 14)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books.

Roth also conveyed that he was in dire straits, the newspaper was in decline, and as soon as the aura of a reporter around him would fade, only the fact would remain that "I was a first-year volunteer. And I would be treated accordingly." He wrote:

"This terrible war has muted our youth. If we survive it, we will already be adults."

Roth was an eyewitness to events that gave him powerful impetus and supplied plots for writing. At the same time, it painfully affected his sense of "self in space" and transformed his worldview. His early works are full of skepticism, despair, and imminent homelessness due to the loss of Home.

Postwar years: creative writing and journalism

There is a legend that Roth was in Bolshevik captivity until 1919. However, there is not a single word about it, for example, in his letter to Kiepenheuer, which contained a few sentences describing his difficult path back from the front. As soon as he reached Vienna, Roth brought poetry written at the front to the editorial office of Der Friede, a political and literary weekly. Fred Heller recalled the episode as follows:

"The soldier gave the impression of a poor, half-starved, frozen man with the old uniform making him appear even more pitiful. He brought two poems. Will we publish them? Sympathizing with the poor fellow, I immediately read them, although our literary editor was usually in no hurry to approve anything. The young soldier's poems were excellent."

Soon, Heller suggested that Roth try his hand at writing reports.

As a young journalist, Roth ignored all possible rules for working with texts, but this did not prevent him from becoming a favorite among the reading public.

In 1920, he hastily left for Berlin and continued to develop his journalistic career. Initially, he received a job at the Berliner Bösen Courier, later starting to contribute to the Frankfurter Zeitung. This cooperation was the longest, and it finally ended in 1933. Roth went on business trips abroad while working for the newspaper, and his texts were extremely popular thanks to their easy and recognizable style.

In 1925, Roth left for Paris. He fell in love with the city at first glance and each time contrasted it with the depressive, tense atmosphere of German cities. Thus, leveraging all his powers of persuasion, he obtained permission to work for the newspaper from abroad. Roth noted in a letter to Bernard von Brentano:

Here is like being on top of a tall tower, you look down from the summit of European civilization, and way down at the bottom, in some sort of gulch, is Germany. I can't write a line in German — certainly not when I am mindful of writing for a German readership. (p. 40)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books.

Roth had a tense relationship with the FZ management: in personal correspondence and appeals to the editorial office, he complained for many years about unsatisfactory pay, poor treatment, censorship, and his requests being ignored. In 1926, he even seriously intended to resign and wrote a farewell letter. Roth could only be held back by the promise of a business trip to Russia and other countries. He took time to think and hesitated for quite a long time, but curiosity won. As a socialist, he wanted to see firsthand the impact of the communist regime and form an unbiased impression:

I am carrying none of the ideological baggage of the sort that mass literary visitors to Russia have carried with them in the last few years. Unlike them, as a consequence of my birth and my knowledge of the country, I am immunized to what goes by "Russian mysticism" or "the great Russian soul," and the like. I am too well aware — as western Europeans are apt to forget — that the Russians were not invented by Dostoyevsky. I'm quite unsentimental about the country, and about the Soviet project (p. 82)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books, 2013.

He spent less time on this trip than he had planned and returned to Europe, finally disillusioned with the communist system. To him, the Soviet world seemed a "terrible apparatus" that deprived one of individuality.

The outcomes of Roth's expeditionary and journalistic work are collected in the Ukrainian-language book Mista i liudy (Cities and People, Books–XXI Publishers, 2023), which consists of four chapters: Journey through France, Journey through Russia, Journey through the Balkans, and Jews: Roads and Roadlessness.

Roth entered a new era as a prose writer with his debut book, The Spider's Web (1923), serialized in the Viennese newspaper Arbeiterzeitung. In the following years, he published the novels Hotel Savoy (1924), Zipper and His Father (1928), Job (1930), Radetzky March (1932), and others. During this highly prolific period, Roth produced 16 novels and many stories, reports, reviews, and letters. In one of his texts addressed to Reifenberg, he shared his most effective writing secret:

"Writing fast is my only option for writing well. Germans write in a scientific way, even fiction. They have a scientific flair. That's why they write slowly."

Roth did not need inspiration and considered the long time taken by other writers only a manifestation of their laziness. After all, if he had a goal to write a novel in three weeks, he could quite realistically fulfill the plan. Impressive, isn't it?

Personal life

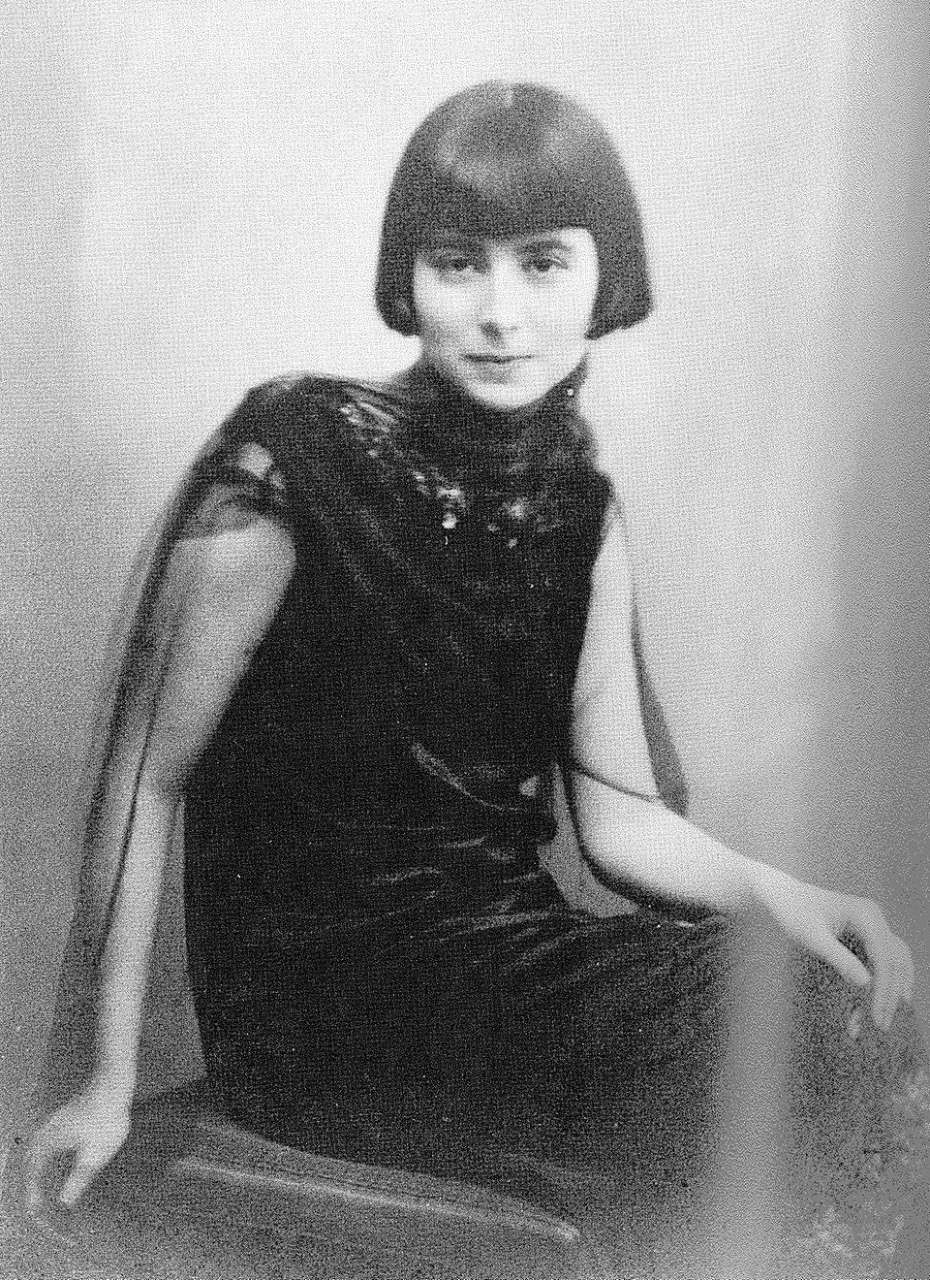

Roth had an uneasy attitude towards women, perhaps due to a problematic relationship with his tyrannical mother or his missing father. If we are to believe the autobiographical accounts, he was little short of Don Juan or Eugène de Rastignac. Returning from the front, he did not plan to marry or enter a serious relationship but met the 19-year-old Jewish beauty Friederike (Friedl) Reichler in the fall of 1919 and won her over from his colleague. When he spontaneously and hastily, without much explanation, moved to Berlin in the summer of the following year, the girl followed him.

They married two years later. However, as early as 1921, Friedl, while still a bride, complained about the lack of attention from him in a letter to Paula:

12 o'clock already, and Muh's still not back, what do you say to that?! Shocking!!!! (p. 25)

From: Roth J. A Life in Letters. Translated and edited by Michael Hofmann. Granta Books, 2013.

Roth's attitude deteriorated rapidly. He would call his wife stupid in the company of unfamiliar people and once climbed onto a table in a café crowded with journalists and accused her of having an affair with a famous musician. Having a predisposition to mental illness, Reichler could not stand the pressure and was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the late 1920s. When Roth once came to visit her in the psychiatric hospital in Vienna, where she was being treated, Reichler tried to attack her husband. After the incident, they were allowed to see each other only through a peephole. Returning to Vienna, Roth informed his friends that his wife had died, even though Frederica actually survived him by 10 months. (She was killed by the Nazis in 1940 as part of the campaign to eliminate the "mentally defective.")

Decline

The events of the last decade of Roth's life — forced exile, alcoholism, minor and major disappointments, and the loss of his cultural homeland — all led to what was to happen in the finale.

When his wife fell ill, Roth began to drink very heavily. However, even alcoholism did not prevent him from being a good writer and journalist. During this period, he produced his magnum opus, the novel Radetzky March (1932), depicting three generations of a family against the backdrop of the empire's gradual collapse. A year later, copies of his novel were burned by members of the German Student Union in the squares along with other publications as part of the "Action against the Un-German Spirit." Roth was in Germany in the early 1930s and managed to leave for France a day before Hitler was proclaimed Chancellor. His second sojourn in Paris felt more like exile.

After "burying" Friedl, Roth entered several more relationships, including a seven-year affair with the wife of a Cameroonian prince who returned to Africa, leaving her with the children in Europe. She said she had never seen a man with such amazing sexual energy before. It was an emotionally draining, turbulent, and ultimately doomed relationship.

The writer Irmgard Keun became Roth's last lover. She was also his last companion during the trip to Lviv in 1937.

Keun told biographers that Roth began every morning the same way — by vomiting. This "ritual" lasted at least an hour.

Miserable and in debt, Roth died in May 1939 at the age of 44. One account points to bilateral pneumonia and delirium tremens, although the cause of death could also have been a heart attack after he learned that his friend Ernst Toller had committed suicide. Eyewitnesses recalled that Roth asked for something strong to drink even in the last hours of his life, in his death throes.

When Roth was a student, he said in a conversation with Soma Morgenstern:

"I constantly see myself like this: an old, skinny old man. I'm wearing a long black dress with long black sleeves that almost completely cover my arms. It's autumn outside, and I go into the garden for a walk, machinating cunning plots against my enemies. Against my enemies and against my friends, too."

Morgenstern looked at him in surprise, but Roth was serious, depicting this prospect:

"He repeatedly recounted to me these questions and his own answers over the decades, always with the same pleasure, without missing a single detail of the overall picture. Always those long sleeves, always those intrigues. Insidious intrigues. Against enemies and friends."

Unfortunately, Roth did not get to live until old age. He is buried at the Cimetière de Thiais in the Val-de-Marne department south of Paris. Roth was a talented prose writer and journalist, and at the same time, a man of Jewish origin. Physical and spiritual isolation from his cultural homeland in the last years of his life accelerated Roth's internal split, leading to his decline. His return to the German-speaking world occurred several decades later. Today, Joseph Roth is one of the most famous classics of German and Austrian literature.

Maryna Horbatiuk

Maryna Horbatiuk

Poet, PR manager, and PhD student at the Department of Literary Theory and Foreign Literature, Faculty of Philology, Yurii Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Chytomo

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

This material is part of a special project supported by Encounter: The Ukrainian-Jewish Literary Prize. The prize is sponsored by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization, with the support of the NGO "Publishers Forum." UJE was founded in 2008 to strengthen and deepen relations between Ukrainians and Jews.