"Karaites made a great contribution to Ukraine's development," says a Ukrainian Karaite Association member

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk, a member of the Advisory Council on Indigenous Peoples at the State Service of Ukraine for Ethnic Policy and Freedom of Conscience, speaks about the Karaites and their cultural heritage.

Discovering Karaite background

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Today, our Encounters program is about the Karaites, and we are happy to have in our studio Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk, a member of the Ukrainian Karaite Association and the Advisory Council on Indigenous Peoples at the State Service of Ukraine for Ethnic Policy and Freedom of Conscience. Could you share your personal story? How did you join the association? Could you also tell us about your family?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Unfortunately, my family story is a poignant example of losing ties and, I would even say, ethnic identity. Due to the political and social pressure of those times or the family's inability to preserve family values, I only heard stories about the Karaites from my grandmother in my childhood. I perceived them as interesting legends that had nothing to do with reality.

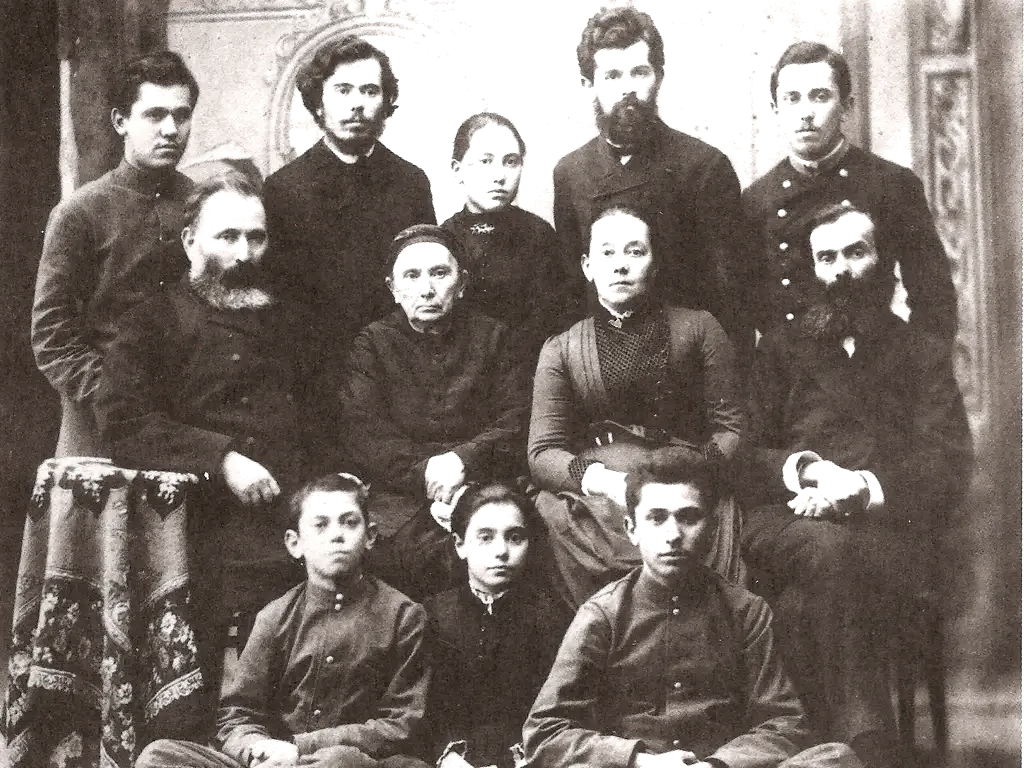

However, as my mother and I joke, I heard the "call of my people" over time, and we began consciously searching for information. Unfortunately, my grandmother had already passed away by that time. However, we have greatly benefited from the activities of local museums, archives, and libraries, as well as the family photo archive. This way, we were able to go back to the year 1910, when my ancestors moved to Kherson from Yevpatoria. I was born in Kherson, but what happened before had to be sought in the Crimea. However, the Crimea had already been annexed by then and was inaccessible.

Karaite families always had many children, so family trees branched out nicely, even as they were not necessarily deep. We found our very distant relatives and started communicating closely with them, exchanging knowledge, stories, and legends.

During [Russia's] full-scale invasion, one of these relatives invited me to join a closed group, "Karaites of Ukraine," on a social network. That's how I got into the association.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What have you discovered about your ancestors that you could share with us?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: My great-grandfather's brother was a professor of veterinary medicine. I learned this thanks to digging deep into museum collections. Their sister was the first female captain. But this is more of a legend, as we have not found any other academic sources confirming this.

I was thrilled to learn that there was a kenesa in Kherson, but it was destroyed. Many archives were moved to Mykolaiv.

One of the grocery stores belonged to my family. We even found a newspaper clipping with the Karaite last name Pembek, still written with a hard sign at the end. It's exciting to learn that there are such notable events and people in your family.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How was the Karaite identity articulated in your family?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Unfortunately, as I said, it was only in my grandmother's stories. There was nothing else. I know other Karaites passed down everything from generation to generation: recipes, books, and some valuable things. Unfortunately, this was not my case, but I do have old photos.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: For me, the 2000s were a period when Ukrainian society was not ready for others. Differences were silenced in every possible way, which might have been the Soviet legacy. What is your view on how the identity of indigenous people was oppressed? What is the situation now? There seems to be more curiosity and interest than fear or condemnation.

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Yes, I agree with you that there is great interest with people asking: "Who is this?"; "Where are you from?" And we are proud of our ethnic background. After all, there were highly educated, talented, and intelligent people among the Karaites: scientists, cultural figures, and doctors. And they made a great contribution to the country's development. That is why we are proud of it. I have brought up this subject multiple times, and we haven't encountered any bullying or other forms of rejection.

A historical note on the Karaites

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Let's give our audience a brief historical note on the Karaites. Where did they come from, and where did they live? What faith do they profess?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: The Karaite ethnic group was formed as a result of a very long and difficult process, which had to do with wars, resettlement of peoples, and changing governments and systems. Most importantly, this group emerged in the Crimea. While researchers trace it back to the beginning of the 5th century BCE, its formation as an integral phenomenon was completed approximately in the 17th century.

The 13th and 14th centuries had a profound impact on our ethnic group and the dialects of our language. Some communities were evicted to Halych and Lutsk in the 13th century, and others to Lithuania in the 14th century. This gave rise to the Galician, Lutsk, and Trakai (Lithuania) dialects.

Our language experienced a significant influence from Byzantium sometime in the 13th century, which brought many Greek names. The Turkic language had an impact later, but the sacred language is Hebrew.

As far as religion is concerned, Karaism is best considered a denomination rather than a religion. Karaites have traditions, but they do not limit themselves by some rules, rituals, etc.

Religious services are held in the form of community gatherings and common prayers in the spirit of unity. People read a siddur, a prayer book with a general structure of quotations from the Torah and Psalms of David. Its content may differ depending on the needs of a particular community.

On modern Karaites and Karaite cultural heritage

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: How many Karaites are there in Ukraine?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: About 2,000 Karaites were registered worldwide when the last national census was held in Ukraine in 2001. Now, 23 years later, it's scary to imagine what the current number might be.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Preserving cultural heritage must be challenging in these conditions. Are there any places where people can come and see artifacts of Karaite culture?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: I will mention the biggest centers. One is Chufut-Kale. Located in the Crimea, it is currently inaccessible due to the Russian annexation of the peninsula. There were also the funds held in kenesas and two huge collections of Abraham Firkovich, which he collected all over Eurasia. However, they were also confiscated and taken to the Saltykov-Shchedrin Library in St. Petersburg. Their current location and condition are unknown.

Kenesa architecture can be seen on 7 Yaroslaviv Val in Kyiv. The building of a kenesa there now serves as the Actor's House. There is another kenesa in Mykolaiv, and Ukraine's only operating kenesa is located in Kharkiv.

There is also a literary heritage and a published catalog of tombstones with family histories, which is a very interesting volume.

Now, during the full-scale invasion, the main repository is the museum of the Karaite community in Halych. They are always happy to give tours. So, if you are traveling through Halych, contact this museum.

The most valuable things are kept in families and passed down from generation to generation. One of the long-standing traditions is for women to write down culinary recipes, medicinal recipes, prayers, and hymns in their notebooks. These notebooks even had a special name. A notebook like this in your archive is a treasure.

Karaites in World War II

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What do we know about the Karaites of the Crimea during World War II? How did they fare?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Unfortunately, this issue is not simple for any of the indigenous peoples. The German occupation authorities did not issue any official decree to exterminate the Karaites. However, due to local denunciations, the Karaites were shot together with the Jews. But this did not happen everywhere. We know of many cases when people, on the contrary, helped Karaites to hide and avoid death. Many Karaites also served honorably, defending their homes, and even received awards. Unfortunately, this is still happening: the descendants of those Karaites have to fight now.

Ukrainian Karaite Association and its activities

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What are the current activities of the Ukrainian Karaite Association?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Today, the association's main goals are, of course, rallying people together and supporting our brothers and sisters because, as I noted earlier, there are very few of us. We are indeed relatives to one another, although very, very distant ones. So, the most important thing for us is to stick together and maintain public presence as much as possible because we really need support from the state.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: What kind of state support do you need exactly? I understand that institutional support is crucial for preserving things on the state level. Is there something else, something palpable, especially now, during full-scale invasion?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: Our first and strongest desire — and everyone will support me here — is peace in the country. As soon as this issue is resolved, we will be able to voice global issues. Number one is enforcing the law on indigenous peoples, adopted in 2021. It gave us the official authority to put forward demands.

I would also like to note, in general terms, that we have advocated restitution and repatriation. Of course, it sounds a little unclear in our present circumstances, but we want to create a Ukraine that every Karaite in the world will know as their ancestral home, where they are always welcome. That is, no matter what happens, they will always be able to return here, meet their people, and come in contact with their heritage.

On multicultural dialogue in Ukraine

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: Today is the World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development. How can we develop this dialogue and development in Ukraine and Ukrainian society?

Yelyzaveta Lytvynchuk: We need to talk about different cultures openly and a lot — at mass events and on social networks. Every Ukrainian should know about the ethnic groups living here. The wealth of cultures creates mutual support and healthy competition, which, in its turn, stimulates the development of society and the state. Therefore, I think this is precisely the advantage that we should strive for, and, of course, we have no right to turn our eyes away from indigenous peoples and avoid mentioning them.

Yelyzaveta Tsarehradska: It's crucial for all of us to get involved and learn more about indigenous people, such as by visiting museums, as you mentioned. Even if you don't have a Karaite background or any Karaites in your milieu, it is still the heritage of our Ukrainian state and part of our great and diverse culture.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.