Leonid Finberg: "Solidarity between Ukrainian and Jewish intellectuals is very important"

LB.ua is launching the publication of a series of interviews within the framework of the focus-theme of "Culture in the Expectation Mode" launched by PEN Ukraine 2020/2021. The first conversation is with Leonid Finberg.

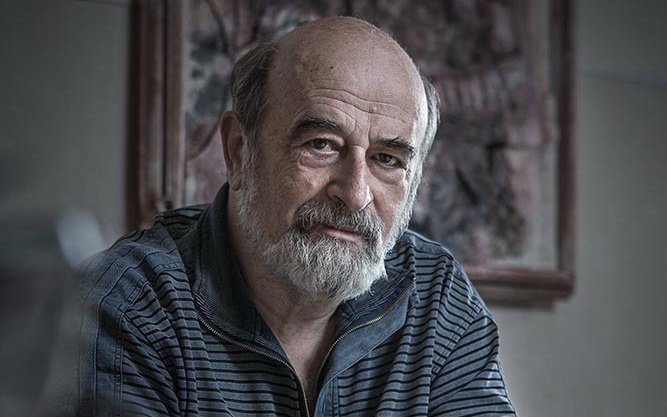

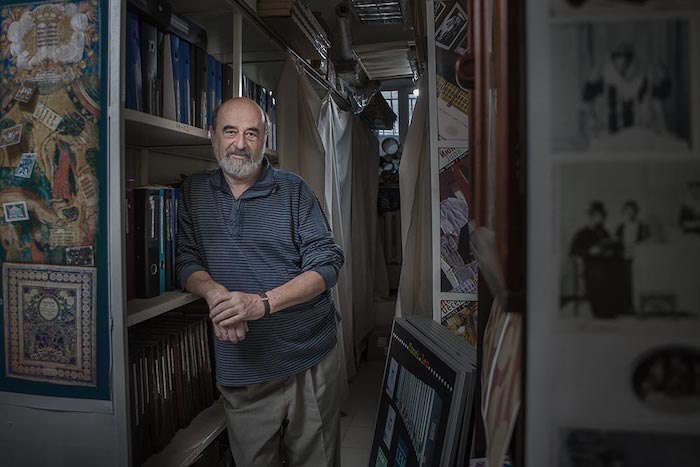

Leonid Finberg is your classic "public intellectual." He is actively creating an intellectual and cultural climate and speaks publicly on important civic issues. He is the editor in chief of Dukh i Litera Publishers, director of the Center for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry, a member of the Executive Council of Ukrainian PEN, a sociologist, a cultural and social researcher, author and organizer of culturological broadcasts, curator of exhibits, and an activist. With Mr. Finberg, sometimes it is important to simply "check the clock" of understanding realities. This time, however, there was another reason for this conversation: the awarding of the Stanislaw Vincenz Prize to Mr. Finberg. (Vincenz was a Polish writer, philosopher, and translator who lived and worked for a long time in today's Ivano-Frankivsk.) The prize honors achievements in the humanitarian sphere and humanistic ideals.

We talked at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy on Sunday in his empty office that is filled with books, albums, paintings, sculptures, and items from Finberg's marvellous collections, including Kyivan brick and typewriters. In this atmosphere, Finberg's level-headed and calm words about dramatic contemporary or historical problems sounded especially persuasive.

"It is best when intellectuals deal with issues of memory and history"

Congratulations on your new distinction, the Stanislaw Vincenz Prize! How do you feel about receiving this award?

Thank you! It is gratifying that our work and that of Dukh i Litera Publishers and the Center for the Studies of History and Culture of East European Jewry is recognized and valued by the community. We really do work quite a lot. Last year alone, we published sixty books, and each of them is important and valuable. We have had triumphs. For me, it is very important that we ourselves are choosing books for publication and that we have so much professional experience that we know how to do practically everything that is necessary for this, and we are in no way inferior to our foreign colleagues. For example, recently, we published the proceedings of the 1908 Chernivtsi conference on the Yiddish language in four languages (English, Yiddish, Ukrainian, and Russian) and did the layout and editing ourselves. Ten years ago, this would not have been impossible to imagine. Or the project "Cultural Figures," a series of biographical publications about Ukrainian historical heroes.

A nation should know not just about the history of events but the subjects of history as well. We began to look around for a person who could do serious research on the biographies of cultural figures and to write about them in an interesting way, not so that it would sound like instructions for a vacuum cleaner. It turned that some people write only in a scholarly style, while others improvise excessively. But Andriy Puchkov, for example, in his books on the historian and philologist Yulian Kulakovsky and on art historians and architects, very ably blends biography with aesthetic analysis. Leonid Ushakov's books about Hryhorii Skovoroda and Mykhailo Drahomanov or Volodymyr Panchenko's books about Mykola Zerov turned out brilliantly. The new books in the series are Eleonora Solovey's study of Ukrainian cultural figures and Dmytro Horbachov's study of early-twentieth-century Ukrainian artists (Knights of the Starving Renaissance—what a title!). I am pleased that in our country, there is an elite that reads our books. The world perceptions of intellectuals are formed by such books.

Vincenz's name is connected to the dialogue between nations, memory, and culture. You have been working for many years on this kind of understanding. Do you feel that the situation in this sphere is improving?

In the last thirty years, we have managed to overcome many Soviet stereotypes in the civic thought of intellectuals. These stereotypes were implanted over a number of decades; they were intricately developed. According to them, Jews were exploiters of Ukrainians, and Ukrainians were antisemites who killed Jews and dozens of more constructs. In fact, the Russian mass media is continuing its efforts to impose similar concepts on us. All of us together—Ukrainians, Jews, Crimean Tatars, and Russians who are living in Ukraine—have done much to debunk these stereotypes. Generally speaking, in any kind of relations—Ukrainian–Jewish, Ukrainian–Polish, Ukrainian–Crimean Tatar, and others—there are no conflicts that cannot be understood if there is goodwill. It is best when intellectuals deal with these questions. It is worse when politicians take on these roles.

What other achievements can we celebrate?

For example, solidarity between Ukrainian and Jewish intellectuals is very important for me. It materialized at the end of the last century. Thus, when provocative articles aimed against Ukraine were appearing in the Israeli media, we, the representatives of the intellectual milieu of Ukrainian Jews, clearly stood up in Ukraine's defense. It is important to conduct proper historical research. This is the best way to dismantle stereotypes. There are many such studies today, but it was no easy task to initiate them. After the [fall of the] Soviet Union, the historical memory of our citizens was very damaged. I will give you an example. At one time, we were collecting the archives of Jewish writers who wrote in Yiddish in the Soviet Union after the Second World War. Yet none of the children of these writers spoke Yiddish. This language was feared. It was "leprosy," a marker of danger, a sign of nationalism.

What is your assessment of the activities of the new administration of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory? The director, Anton Drobovych, has been working for almost one year. His arrival was accompanied by both trepidation and expectations.

In his position, Volodymyr Viatrovych accomplished quite a lot. His main achievement, in my opinion, is opening the SBU [Security Service of Ukraine—Ed.] archives. He also did a lot for the decommunization of society. However, I have my doubts about whether it was necessary to work so intensively to change Soviet totalitarian heroes to totalitarian or authoritarian Ukrainian heroes. It would still be worthwhile to carry out a more liberal policy. In my view, the Institute of National Memory is continuing to do the right things today, for example, decommunization. It has a balanced attitude to interethnic and interconfessional contradictions. In other words, my impressions are positive. Incidentally, we are interacting with the Institute, collaborating on the publication of a series of books about the Second World War. This is badly needed because we still lack new, systematic publications about the war, which to this day has been treated mostly in the Soviet manner. Together we have already published Olena Stiazhkina's book Castling: Four Essays on the History of the Second World War. It is a pity, however, that the Institute of National Memory, being a state institution, does not have the right to sell the book. Therefore, we agreed that the Institute will finance the publication costs, take delivery of the books, distribute them to civic organizations and researchers, and post it on the Internet. In general, this legislation is complete nonsense. Due to this, a pile of important books are lying in the basements of academic institutions, which simply cannot be put into circulation. You have written a study, gifted it to friends, but what comes next if you cannot place it in bookstores or on the Internet? I don't understand why to this day, the academic community has not demanded a solution to this question, which would increase the importance of Ukrainian scholarship.

You mentioned the lack of a systematic view of the Second World War. Why is this still the case?

Every process must mature. For example, the children of Nazis had no great desire to talk about their parents' actions. In Germany, an understanding of what happened came with the generation of the grandchildren of those who participated in these events. But even so, many people have no desire to think seriously about this tragedy and acquire serious knowledge about it. I was once part of a Ukrainian delegation in Germany. We were driven around to commemorative sites, particularly former concentration camps, and with us traveled Germans, especially students. We were invited to talk about the Second World War with these young Germans. I decided to take part in this conversation. To all my questions, the students replied the way it was written in textbooks. They answered the way they thought was expected of them. Then I asked whether they knew what specifically happened in their native cities during the Nazi period. Out of approximately twenty students, only one girl was able to offer an answer. And when I asked whether they were aware of what their relatives had done in those years, I did not receive a single answer. Because for the human psyche, it is very difficult to feel that someone among their relatives was a hater of mankind and killed people. There are some cases where people are not afraid to talk, especially when this is reinforced by art, and they become important for all mankind. This is also relevant for Ukraine.

"During the Soviet period, the Holocaust could not be understood"

The Holocaust. Are you continuing to work on this topic?

It so happened that for Europe, the Holocaust became the model for understanding the savagery of humanity. In Europe, in general, the war was also waged with minimal rules in mind. For example, prisoners of war could obtain packages from their families. Initially, the kind of savagery that took place on the territory of the USSR did not occur in other Nazi-occupied countries and on other fronts. Thus, the Holocaust in our country was the most horrible. In Western ghettos, it was extremely difficult to survive, but it was simply impossible to survive in Babyn Yar and other similar places. Like in POW camps, where people died like flies. The word Holocaust in the West and the East is one and the same, but the histories and events are different. More than twenty thousand monographs have been published throughout the world about the Holocaust; the civilized world shudders from the accounts of these horrors.

During the Soviet period, the Holocaust could not be understood because independent research by definition did not exist. The archives were closed, and ideas about the war years were under pressure from visions of power. This applies even to language, where the "Great Patriotic War" became a commonplace concept, a term that grossly distorts reality and seeks to negate the fact that during the first two years of the Second World War, the Soviet Union was Hitler's ally. Everything was reflected in distorting mirrors. For our colleagues and us, this became a challenge. We understood that it was necessary to understand the horrors of the Holocaust in our land. And we began to record reminiscences and help Yad Vashem in Israel to search for people who had rescued Jews and to publish books.

However, in many respects, we were too late. When the USSR collapsed, most eyewitnesses were no longer alive. And many people were afraid. They were too used to the fact that the USSR did not encourage talk about the Second World War as a tragedy. It was supposed to be a triumph, a victory. (Vladimir Bukovsky questioned whether those who had lost four times more people during the conflict were victors or the vanquished. The question is rhetorical.) We published nearly thirty books about the Holocaust, but countries with a more peaceful history have published thousands. One of our finest books on this topic is Liudianist′ u bezodni pekla: Povedinka mistsevoho naselennia Skhidnoї Halychyny v roky "ostatochnoho rozv'iazannia ievreis′koho pytannia" (Humaneness in the Abyss of Hell: The Behavior of the Local Population of Eastern Galicia during the Years of the "Final Resolution of the Jewish Question") by Zhanna Kovba, our researcher, who is no longer with us, unfortunately. A man from the Ukrainian diaspora told me that he had been waiting for this book his whole life. We did a Ukrainian translation of the collection Holocaust: Religious and Philosophical Implications. Or the diary of David Kahane, a rabbi who was rescued from the Lviv ghetto by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. I think that we have made our contribution to understanding the Holocaust. You know, in the past Ukrainian intellectuals often said: "The Holocaust is your tragedy, the Holodomor is ours." Today I see much more appreciation of the commonality of our tragedies, a perception of them as all-Ukrainian ones.

Here we cannot overlook the discussions about the memorial and museum in Babyn Yar.

The attention to Babyn Yar did not crop up today. We even created an exhibition about it called "The Struggle for the Memory of Babyn Yar." The first design for a memorial on this site appeared back in 1945, but we were not able to turn it into a reality because of the antisemitic policies of late Stalinism. But later, as I have said, people started talking about the Second World War in the context of victories, not victims and losses. However, people themselves honored the memory of those who had been killed. The Black Book [of Soviet Jewry], edited by Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman, was prepared, but it never came out (we published it in the Ukrainian language this year). There were works dedicated to Babyn Yar by Jewish and Ukrainian poets. A turning point that contributed to the transformation of memorylessness into memory was the marvellous poem by the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. There were also illegal commemorations of the Babyn Yar victims; there are extant photographs showing how many young people—not just Jewish youths—would come from all over the USSR on the anniversaries of the shootings. Of course, the KGB kept track of this. They would station next to themselves elderly Jews who knew Yiddish and could read the inscriptions on, say, funeral wreaths, and if they saw something along the lines of "Death to antisemites!" (there were cases like this), the wreaths were confiscated. Of course, the Star of David was banned, as was the tryzub [trident, the Ukrainian national emblem]; it was considered a nationalistic symbol. Nevertheless, resourceful people managed to carry two separate triangles past the controls, which they later placed together to make a Star of David. There were trials; there were convictions. They tried, through fear, to quash people's desire to remember their relatives.

Did you attend these meetings? I think I saw such a photo.

That's true. But I was around already in the 1970s. Earlier, in the sixties, when the first meetings where Ivan Dziuba, Viktor Nekrasov, and Amik Diamant delivered speeches were taking place, I was still too young, and I understood too little. In the seventies, on days commemorating the events in the vicinity of Babyn Yar, all transportation stopped, and it was impossible to call for a taxi. People had to go on foot. And as a preventative measure, activists were arrested or sent on business trips.

During the Holocaust, victims went on foot, too. There's a kind of eerie symbolism here.

Yes, it's very symbolic. However, restrictions did not help; people went anyway. Later, the authorities decided to seize the initiative and officialize meetings where "proper" Jews, Heroes of Socialist Labor, or heads of enterprises, delivered speeches condemning Zionism. It was much freer in the late 1980s, of course. I already knew about Yad Vashem's questionnaires, which were used to collect the names of those who had been killed, and I myself created similar questionnaires; ten thousand leaflets. Our children and the children of our friends distributed them to people who were going to Babyn Yar. That is how we managed to collect approximately five thousand names. Earlier, other activists had collected the same number.

In the 1970s, I was following the competition for monument designs. I remember the very interesting design by Ada Rybachuk and Volodymyr Melnychenko, the designs of Yosyp Karakis, Borys Liekar, and others. But the government decided otherwise, and a monument appeared with a nonrepresentational inscription about Soviet citizens, soldiers, and officers who were shot by the Nazis, without a single mention of the Jewish tragedy.

Today there are two projects. Two communities are proposing to immortalize the memory of those who were killed in Babyn Yar. The first is a group of Ukrainian scholars with the concept of honoring this memory and creating a museum. The second is the international Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center. The concept for a Holocaust center and Babyn Yar museum was presented at a meeting held at Taras Shevchenko University. The majority of scholars in attendance gave a negative assessment of this project. Later the patrons of the project—American businessmen from Russia who are connected with this country—changed the team. By the end of the year, they promise to reveal what the new team will be doing. But the theses outlining the principles and aesthetic criteria of the artistic director Ilya Khrzhanovsky sparked protests from intellectual circles. I rejected his aesthetics too. I am convinced that the pathos surrounding the narrative should have a feedback loop with the pathos of the event. I value the concepts put forward by Claude Lanzmann and Serhiy Bukovsky in the conceptualization of the tragic experience of the Catastrophe. They seem outwardly calm, and this makes them even more impressive. But I—and I am not the only one—do not accept naturalism or the media-type reproduction of horror.

The position of the Ukrainian authorities is important. I can't imagine giving away the right to honor your tragedy to another community. I consider the Ukrainian government's Memorandum of Cooperation with this center one of several unprofessional—to put it mildly—statements and actions; for example, the declaration of the notion "What's the difference?" applied to linguistic and historical topics, discussions of water for the Crimea, and the "survey" that was held for incomprehensible reasons during elections.

What if the Memorial Center invites you to collaborate?

The center's representatives have already contacted us. They asked about the possibility of providing them with additional copies of some of our publishing house's important books. I thought about it and agreed.

Why?

This is a reinforcement of our positions and contexts. Likewise, we will not be hindering them from working with our archives if they want. In general, I do not exclude the possibility that civic society will force the "Varangians" to take Ukraine's national interests into consideration, no matter what the government's position. With our Maidans, we have already proven that this will happen many times over.

"We have a week to learn how to live underwater."

From history to the present day. How do we continue intellectual work in the conditions of the current global crisis, when questions of culture, art, memory and scholarship are being openly shunted aside?

We need solidarity among intellectuals; we have to unite our efforts, create powerful associations so that our word will be heard better than it is today. Moral authorities play an important role here. I also mean dissidents: Josef Zissels, Myroslav Marynovych, and Vasyl Ovsiienko, and those who demonstrate courage and invincibility in the confrontation with Russia, protest against inadequate governmental decisions regarding the Maidans. This is a powerful force, but it is still not sufficiently organized.

One challenge is the mass shift online of events, institutions, and many other things.

The pandemic and its consequences are a challenge, but it is by far not the first and likely not the worst one in the history of mankind. For example, was Chornobyl not a challenge? Or the plague in medieval times? Everything will depend on the creativity of responses. I know of structures that have found positive aspects in these conditions. Thus, it has become easier to hold conferences, especially international ones. Right now, many educational and scholarly institutions are organizing them online. I am not saying that this is better; simply that this is one case where we have succeeded in taking advantage of the situation. Obviously, it is difficult for everyone; it is difficult for schoolchildren and especially difficult for the parents of schoolchildren. I will quote the latest popularity: Humanity learns that a global flood will begin in a week's time. In keeping with the stereotypical behavior of various nations, some decide to drink as much vodka as possible; others to make love non-stop. But the wisest say: "We have a week to learn how to live underwater." Therefore, let us learn.

There is also the question of whether education itself will be ruined in the process.

Our education is so Soviet, so little changed that it is the least threatened by the pandemic.

One of the manifestations of the systemic crisis is populism, and not just in politics, which is discussed more, but also in culture, where we are seeing emphasis placed on temporary, mass things.

High culture has always been in the minority—always, in all periods, in all nations. There is no other way to struggle for high culture. But, of course, the possibilities afforded by computer technology and the Internet have created new behavioral models. For instance, in the past uneducated people participated less in solving important problems of humanity, but today they "have gotten a voice." Research has shown that many people, under the influence of mass media manipulations, make a choice without understanding their actions, without understanding the real state of affairs, without understanding the consequences. The media imposes inadequate views. Politicians like Trump and Zelensky exploit this. As the Polish poet Stanisław Jerzy Lec said, "It is difficult to broaden new horizons, but it is easy to look sideways." We need to understand the situation, to make efforts, to seek. I think that it was not easier for previous generations, say, during the Second World War. They faced different challenges, we have ours.

This project is supported by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Oleh Kotsarev, writer and journalist

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @LB.ua

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.