My Sheptytsky

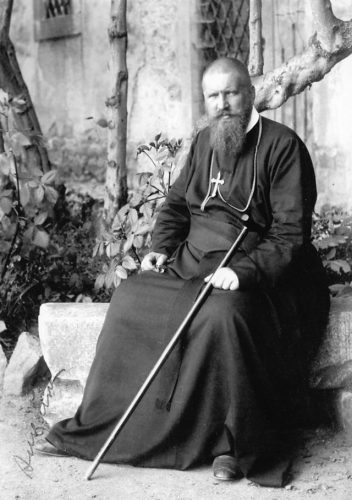

One of the world’s most famous historians of the Holocaust (he himself is a survivor) and the author of “Together and Apart in Brzezany: Poles, Jews and Ukrainians, 1919-1945”, Shimon Redlich remembers the legacy of the great Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. From 1901 until his death in 1944, the legendary Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church personally intervened to save hundreds of Jews from the Germans. The title of Righteous Among the Nations, bequeathed by the state of Israel to individuals who saved Jews during the Holocaust, has never been bestowed upon Sheptytsky. This fact remains deeply controversial among Sheptytsky’s impassioned champions.

One of the world’s most famous historians of the Holocaust (he himself is a survivor) and the author of “Together and Apart in Brzezany: Poles, Jews and Ukrainians, 1919-1945”, Shimon Redlich remembers the legacy of the great Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky. From 1901 until his death in 1944, the legendary Metropolitan of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church personally intervened to save hundreds of Jews from the Germans. The title of Righteous Among the Nations, bequeathed by the state of Israel to individuals who saved Jews during the Holocaust, has never been bestowed upon Sheptytsky. This fact remains deeply controversial among Sheptytsky’s impassioned champions.

This essay originally appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of The Odessa Review, which was supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

The first time that I heard about Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky was sometime in the late 1950’s. I had immigrated from Poland to Israel a few years earlier. Aunt Rachel, my father’s younger sister, who left Brzezany for Palestine prior to World War II, told me that my great-grandfather, Mekhl Redlich, was among those who greeted Sheptytsky when he visited our town before the First World War. As I would learn later, Sheptytsky had indeed arrived in Brzezany for a canonical visit in 1901, and was greeted by local clergy with crosses and by Jewish rabbis carrying a Torah scroll.

For years, I had a very vague notion of Sheptytsky and his relations with Jews. It was only in the mid 80’s, when I was a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute and was invited to present a paper on “Sheptytsky and the Jews During World War II” at Toronto University, that I began immersing myself into the story of Sheptytsky’s life and conducting research on the Metropolitan’s complex relations with Judaism and Jews. My interest in a Ukrainian who saved Jews during the Holocaust wasn’t accidental. My close family was saved by a Ukrainian peasant woman from the village of Raj, near Brzezany (today in Western Ukraine), and in those times part of Polish Eastern Galicia. At the Toronto Conference on Andrei Sheptytsky I was surrounded, for the first time in my life, by dozens of Ukrainian scholars and priests from all over the world. This was both exciting and strange for me. I was getting closer to a milieu that was both near and distant at the same time. I met there the late Kurt Lewin, a prominent survivor saved by Sheptytsky, who throughout his postwar life spoke and wrote about the Metropolitan. Kurt was always skeptical of the possibility of an open and honest approach toward the Sheptytsky issue within Yad Vashem.

For the next thirty years, I read and spoke about Sheptytsky. I attempted to be as objective as possible. I distanced myself from both the hagiographic tendencies among Ukrainians and the anti-Ukrainian attitudes among Jews. Shortly after my return to Israel, I published a lengthy article in the Jerusalem Post in which I asked a crucial question: was Ukrainian Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky a saint and savior or Nazi collaborator? I continued reading and probing into that controversial dilemma and reached the conclusion that the Metropolitan was a highly complex personality who lived under unprecedented circumstances of total war and the annihilation of the Jewish population. He faced the Soviet and Nazi regimes and their acts of terror, and hoped against hope that Ukrainian independence might be attainable. He was aware of the young Ukrainians’ extremist national tendencies and of the fact that some Ukrainians denounced and murdered Jews. I believe that he was torn between his humanism and his nationalism. Although in the early days of the German occupation Sheptytsky, somewhat naively, believed that Hitler would support Samostiina Ukraina (Independent Ukraine), with time he grasped the enormity of the evil of Hitler and Nazi Germany. Time and again, he wrote about this to the Holy See in Rome. Sheptytsky was a humane Ukrainian spiritual leader, who not only saved individual Jews, but also spoke out publicly and privately against their murder.

Some fifteen years ago, I reached the conclusion that my research on and writings about Metropolitan Sheptytsky did not affect the decisions of Yad Vashem. I decided to join the few remaining Sheptytsky survivors in their persistent struggle to have him recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations. Together with the late Professor Israel Gutman, a leading Israeli historian of the Holocaust and a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, and Ambassador Dr. Yosef Govrin, a Holocaust survivor from Romania, I initiated a number of appeals to Yad Vashem. I suggested that we invite several leading historians to evaluate Metropolitan Sheptytsky’s attitudes and deeds during the war. Professor Gutman was ready and willing to meet with Judge Yaakov Turkel, Head of the Righteous Committee at Yad Vashem.

Yad Vashem didn’t even respond to my suggestion and Judge Turkel refused the meeting.

I succeeded in getting several Israeli journalists to write about the Sheptytsky story for widely read Israeli newspapers and magazines such as Haaretz, Maariv and The Jerusalem Report. I also continued discussing the Sheptytsky issue at academic conferences in Israel and abroad. The first ever Conference on Sheptytsky in Lviv in 2005 was a milestone for me, both as scholar and as a child survivor saved by a Ukrainian family in nearby Berezhany. I convinced my close friend Mrs. Lily Pohlmann, who had been saved by Sheptytsky, to travel and participate in that Conference. I accompanied her to Metropolitan Sheptytsky’s crypt at St. George’s Cathedral. I have also been corresponding for years with another Sheptytsky survivor, former Polish Foreign Minister Adam Rotfeld, and we met for the first time in Kyiv last year.

While work was taking place on “Shimon’s Returns”, a documentary on my recurring visits to Ukraine and Poland several years ago, I insisted on including a visit to St. George’s in Lviv. It was during that visit that I went again to pay tribute to the Metropolitan at his crypt and also spoke with Sister Chrysantia, the oldest surviving person who knew Sheptytsky personally when she was a young nun. She spoke about Sheptytsky with the greatest reverence and admiration.

The latest Sheptytsky-related event which I’ve attended was the 75th anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacre in Kyiv last September. The anti-Soviet dissident and literary critic Ivan Dziuba was awarded the Sheptytsky Medal. Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko mentioned both Sheptytsky and Dziuba in his speech at the Babyn Yar memorial ceremony the next day. For years, I have considered both of them my Ukrainian cultural and humanist heroes. I was moved by the President’s honest words as well as by the various ceremonies and cultural events organized to commemorate the victims of Babyn Yar.

Let’s return now to the question of recognizing the Metropolitan as a Righteous Among the Nations. Over the years, attitudes toward Ukrainians within Jewish communities worldwide have mainly been negative. At times they flared up, as they did during the John Demjanjuk Trial in Jerusalem in the 1980’s. Within the largest Jewish communities, Israel and the United States, Sheptytsky’s name is quite unknown. The most famous Gentiles who saved Jews during the Holocaust are Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg. Both were recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Gentiles. The late Judge Moshe Beiski — head of the Righteous Committee at Yad Vashem for 20 years and himself a Schindler survivor who was instrumental in having Schindler recognized — had been a staunch opponent of Sheptytsky’s case. A short time before his death, he admitted that he and the Committee might have been wrong. I passed on this information to Yad Vashem with no response. Sheptytsky’s case is still pending, after decades of discussions by the Yad Vashem Committee for the Designation of the Righteous. The latest discussion of the Sheptytsky case was about two years ago. Like all previous meetings, it ended in a negative vote.

It seems that, during the last few years, activities on behalf of Sheptytsky have increased considerably. The Anti-Defamation League, a leading American-Jewish institution, recognized Sheptytsky’s deeds and legacy. We may assume that the recognition of Sheptytsky’s humanitarian legacy by the Canadian Parliament a few years ago also had some effect on the Jewish community. Pope Francis voiced good words about Sheptytsky last year. But still, the crux of the matter, in my opinion, is Yad Vashem. It is my assumption and belief that Sheptytsky’s image as a moral leader and savior of Jews during the Holocaust will never be complete until he is recognized as a Righteous Gentile. Yad Vashem is the supreme Holocaust authority in Israel, as well as among Jews worldwide.

As with overall relations between Jews and Ukrainians — despite the emergence of a “new Ukraine” — serious complexities still exist in both groups’ national collective memories. Ukraine is in urgent need of building up its national heroes. Some of these historical heroes are negative figures in Jewish collective memory. I hope that, in the future, there will be more mutual understanding and appreciation among Ukrainians and Jews. It seems to me that only in such a context can the case of Sheptytsky be discussed in a more objective and detached manner.

Shimon Redlich is Professor Emeritus in History at Ben-Gurion University, Israel. He is the Recipient of “The Order of Merit, third class” from the President of Ukraine.

NOTE: The UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.