Mykhailo Hrushevsky's Ukrainian "lost paradise": the Jewish dimension

Professor Mykhailo Hrushevsky (1866–1934), the head of the Ukrainian Central Rada [revolutionary parliament founded in 1917 that directed the Ukrainian national movement — Ed.] and one of the most distinguished Ukrainian figures of the twentieth century, had a deep and abiding love for his "small motherland," the village of Sestrynivka in Kyiv Gubernia (today: Vinnytsia oblast). Around this village, I uncovered an unusual "Jewish trace" and even found…myself.

Hlafira Zakharivna, the mother of the future scholar, was born and raised in Sestrynivka. At the age of seventeen, she married Serhii Hrushevsky, a 30-year-old professor of the Kyiv Theological Seminary. The village was the life-long home of Hlafira's father, a local priest named Zakharii Opokov, who gave his blessing to his beloved grandson, Mykhailo, ahead of his studies at the University of Kyiv.

During his childhood years and time off from his university studies Hrushevsky visited Sestrynivka regularly. He lived in the native village of his grandfather and mother in 1873, 1876, 1882, 1885, 1890, 1891, twice in 1892, and 1893. The last time that the 28-year-old Hrushevsky, now a professor at the University of Lviv, came to Sestrynivka to make his confession to his grandfather was in 1894, a few months before the latter's death.

In his memoirs, Hrushevsky recalled Sestrynivka with exceptional warmth: "A Ukrainian village, woods, water, the Ukrainian people, the Ukrainian language — all this burst into my soul like some sort of different, better world, to which I could later reach out only with my soul and through daydreams. How enamored I was of this village that, on the outside, possessed all the Ukrainian characteristics: tidy, little white houses, thatched roofs, orchards, gardens, passages through hedges, banks overgrown with willow trees. For me, life in Sestrynivka was one never-ending holiday."

To Hrushevsky the adult, Sestrynivka was a "lost paradise" that he sought his entire life. To put it more colorfully, it was his "place of power," where the great scholar and patriot of his people recharged his batteries by plunging into the elements of the Ukrainian "ocean."

He wrote about this later: "I loved Sestrynivka extraordinarily, I daydreamed about it a lot, and my soul soared to it for entire decades of my life. It was actually the only place where I could connect with the Ukrainian element, touch the Ukrainian soil, its nature, its culture — despite all the shortcomings of the forms in which this element appeared."

From this description, one might hazard a guess that Sestrynivka and its surroundings, celebrated by Hrushevsky, was exclusively Ukrainian. But in fact, this was not the case; by that time, the village was far from the folkloric Ukrainian "gold standard."

In the 1870s and 1880s, a railway stretching from Kyiv to Balta was built not far from the village, and a large railway junction, together with a beautiful station, was being built in Koziatyn, a few kilometers from the village. The men of Sestrynivka headed there to earn a living, and the village began to take on a suburban character.

Urbanization, the nearby railway, and the development of trade brought Jews to Sestrynivka.

In Hrushevsky's diary, we see the following journal entry recorded under 2 November 1890: "Here I am once again in Sestrynivka, although before I reached it, I thought that it would be better not to go. I had to trudge somewhere with a Jew and climb over fences, sit in his house (although it was quite clean; here is another thought that struck me: I heard the Jewish woman chatting with her daughter, and then I hear the little child snuffling and smacking its lips, this surprised me, it was as though I had thought that the sleepy child and the like would be different from a Christian child, or something). Along the way, I overturned, had to lift the wagon."

The most likely explanation is that the described incident concerned a Jewish wagon driver who was bringing the scholar from the Koziatyn railway station to the village. The young Hrushevsky's negative stereotypes of Jews are striking. But it is also clear that he himself "exposes" these prejudices in his journal.

In 1864 Sestrynivka had a population of nearly 2,000 Orthodox (Christians) and 17 Jews. According to the 1897 census, the number of residents had increased to 3,459, of whom 3,306 were Orthodox (Christians). One may suppose that the remaining 153 people were Roman Catholics and Jews.

Koziatyn, the town and railway station closest to Sestrynivka, was home to 6,600 Christians and 1,731 Jews (twenty percent of the total population). Ninety-five percent of all shops, pharmacies, and warehouses belonged to Jews.

Looming over all this was the nearest county center, the city of Berdychiv, with a population of 53,000, 42,000 of which were Jews.

In 1897, the villages and towns of Berdychiv County (excluding the city of Berdychiv) were home to 177,000 Orthodox (172,00 of them Ukrainians), 25,000 Catholics (11,000 of them Ukrainians), and 23,400 Jews.

During Hrushevsky's childhood and youth, an entire "sea" of small Jewish towns encircled Sestrynivka, which was part of Berdychiv County, Kyiv Gubernia.

On the map below, I have marked in blue only the names of the populated areas that lay within a 70-km radius of Hrushevsky's "small fatherland," which had a Jewish population reaching thirty to forty percent and, in some cases, between fifty and sixty percent.

Some of the Jewish towns indicated on the map were also centers of several Hasidic dynasties: Makarov (Ukr. Makariv), Skver (Ukr. Skvyra), Ruzhin (Ukr. Ruzhyn), and Machnovka (Ukr. Makhnivka).

A look at the map prompts the following question. Were Jewish towns islands in a "Ukrainian sea" or the contrary: Were Ukrainian villages in this region surrounded by and under the influence of Jewish towns?

Perhaps the answer lies in mutual influence and the economic interconnection between Ukrainian villages and Jewish towns, all of which was ripped asunder by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s and 1930s, and later physically destroyed during the Holocaust.

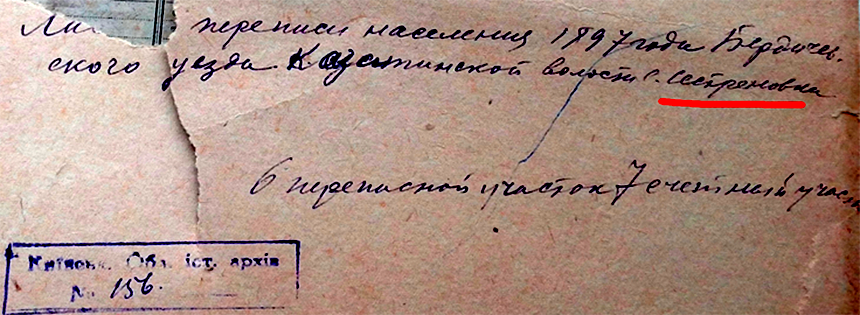

Some Jews in Sestrynivka appear in an archival file dated 1897.

The lists of the first general census in the Russian Empire report, for example, that a Jewish family, the Brimans, resided in Sestrynivka.

It consisted of 50-year-old widow Malka Avrumivna Briman and her three adult sons; she owns two shops in the village: one selling kerosene and the other — a grocery store. The oldest son, 23-year-old Hersh Berkovych Briman, helps his mother in the kerosene shop.

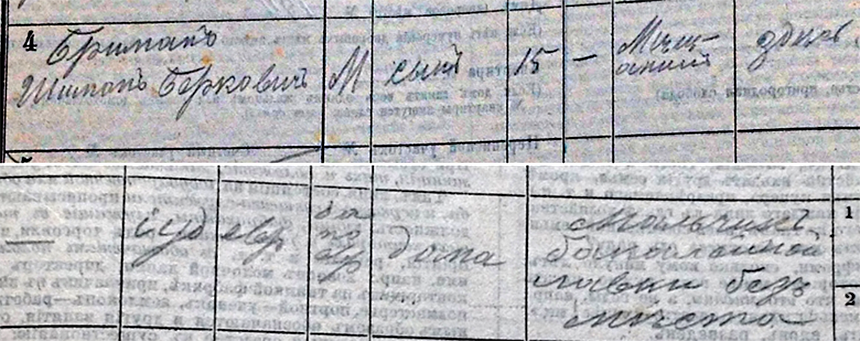

The middle son, 20-year-old Froim Briman, works as a clerk at the grocery store. The youngest, 15-year-old Shimon Briman, helps the middle son. Shimon's type of activities is indicated as "boy at a grocery store without a position."

All four Brimans are listed as being of the Jewish faith, literate, who know how to read the Jewish language, studied at home, and were born here, in Sestrynivka. There is no doubt that in living in the Ukrainian village and trading with the local inhabitants, the Briman family knew the Ukrainian language.

It must be noted that Jews were formally barred from living in any rural areas of Kyiv Gubernia; an imperial ukase about this was adopted back in 1830. Later, the "Temporary Rules" of 1882 barred Jews once again from residing in villages throughout the Russian Empire.

Therefore, the fact that the Briman family lived and engaged in commerce in Sestrynivka for dozens of years means that the local community had given them permission to do so. And as was customary in such matters, the local priest played a huge role in the matter of granting such approval. From this, I infer that Hrushevsky's grandfather, Zakharii Opokov, an authoritative figure among his fellow villagers, helped the young widow with three children to remain in the village and earn a living.

The widow Malka Briman from Sestrynivka was the aunt of my great-grandfather, Yakiv Briman, who lived for many years in Berdychiv and the surrounding towns, managing the estate of a Polish countess. His son, my grandfather Semén (Shimon) Briman, was born in 1904 in the town of Korostyshiv, in Kyiv Gubernia.

After the death of his first wife during childbirth, my great-grandfather returned to Berdychiv in 1906, and married the younger sister of his late wife and remained in Berdychiv, where he managed a mill (later, he and his wife perished during the Holocaust).

The upheavals of the revolution and the Civil War destroyed this old world.

In keeping with the new administrative division, Sestrynivka ended up in Koziatyn raion in Vinnytsia oblast. The forcible creation of collective farms and the confiscation of grain from the peasantry led to the horrors of the Holodomor.

A report prepared by the head of the Koziatyn raion division of the OGPU [Soviet secret police] and sent to the secretary of the Vinnytsia oblast committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine states that between 15 March and 15 April 1933 alone, 68 people developed starvation edema in the village of Sestrynivka. Then came the most terrible months of starvation, when the mortality rate rose sharply. It is entirely possible that up to five hundred villagers starved to death in Sestrynivka, the once prosperous and blossoming Ukrainian village of Mykhailo Hrushevsky.

That Chekist's report states that the starving inhabitants of Sestrynivka go to the fat-rendering plant and open up the cattle mortuary filled with diseased animals, including dead horses, dogs, and cats. "After a fire broke out in the village of Sestrynivka at the collective farm stable next to a pit where the bodies of dead horses were buried, people, mostly women and children, dug them up several times, cutting the flesh off the bones and picking apart the bones," the Chekist wrote.

This same document notes that Leiba Kriger, a former Jewish trader from Koziatyn, was conducting conversations with the peasants along these lines: "How long will the government starve us, what is this, why be silent? They are not giving out grain; there is no work; they don't allow trading either. The authorities want people to die of hunger so that they will have more grain to export abroad. Children are starving to death; nearly a hundred people are dying each day in Berdychiv."

A beggar walking around the village of Sestrynivka asked for bread, saying that he was starving to death. "Someone gave him a pickle, the beggar halted and began saying: "The entire peasantry is starving to death; they raised their arms for freedom, and now — croak from hunger! Since the New Year, six hundred people in Koziatyn alone have already died. See what kind of government we have.' The onlookers responded to his words with silent sympathy," the Chekist reported about the residents of Sestrynivka.

At the end of 1941 and throughout 1942, the Nazis killed nearly two thousand Jews in Koziatyn. Murdered along with them were nearly a thousand Jews who were living in the villages of Koziatyn raion. Among them were likely the last Jews of Sestrynivka.

In 2006, on the 140th anniversary of the head of the Central Rada, the Mykhailo Hrushevsky Museum was opened in the village of Sestrynivka. The primary building, his grandfather's house, is no longer standing; it collapsed in the early 2000s.

The current population of the village stands at nearly 1,200 people, a third of the number recorded in the 1897 census. There are no more Jewish traces left in Sestrynivka or all of Koziatyn raion.

Today all I can do is imagine that perhaps the priest Zakharii Opokov or even his grandson, Mykhailo Hrushevsky, purchased kerosene, matches, soap, oil, groats, and tea from my great-grandfather's aunt. That 15-year-old "boy without a position," Shimon Briman, reached quickly for some raisins from the back shelf of the store for Hrushevsky, and then ran through Sestrynivka to deliver the purchases to his house.

Text: Shimon Briman (Israel)

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk

Edited by Peter Bejger