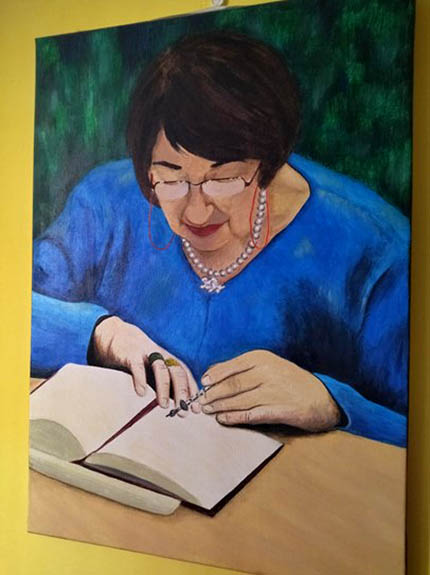

Zofia Radzikowska, a law professor from Kraków and Shoah survivor: "There is only one way out for the world: the international community must partition Russia"

Zofia Radzikowska, formerly Professor of Law at the Jagiellonian University, talks about her unique experience of helping Ukrainians in Kraków, the fight against communism in Poland, and her own experience of surviving genocide.

Kraków was one of the Jewish capitals of Europe before World War II, and most of its population perished in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Today, the Jewish community of Kraków has no illusions about who attacked Ukraine and what modern Russia is. That is the reason why, starting from 24 February 2022, the Jewish Community Centre Kraków (JCC Kraków) has fully supported Ukraine, having decided to provide extensive aid to all Ukrainian refugees. And this is a unique picture for Europe and the world.

In the first year of the war, JCC Kraków directly helped more than 200,000 refugees, more than 98% of whom are not Jewish. It still helps almost a thousand people a day. Every day from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., hundreds of Ukrainian women with children and the elderly come to the Center to receive food, groceries, clothing, medications, toys, and moral and emotional support. They are provided with food, housing, psychological and legal support, daycare, employment assistance, and Polish and English language classes. The Center ships humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

This is especially important because many support centers for Ukrainian refugees across the EU are being closed. All of them were opened in the spring of 2022 but stopped providing support in the summer or autumn. While it is clear why Jewish communities worldwide are helping Ukrainian Jewish refugees, places like JCC Kraków are unique because they provide support to all Ukrainians even a year after the outbreak of the war.

"JCC Kraków helps because it is the right thing to do. The Jewish tradition requires that we welcome the stranger, and we are very much aware of the idea of tikkun olam. The world is a broken place, and we must fix it. With this in mind, I believe that we in Kraków have a special responsibility to help. Eighty years ago, during the Shoah, Jews in Europe were largely abandoned. The world was indifferent to the massacre of Jews. Now, 80 years later, we, the Jewish community located near Auschwitz, can respond to the sufferings of others by either ignoring them or by learning from what happened to us and engaging. We choose to help," says JCC Kraków Director Jonathan Ornstein.

Zofia Radzikowska, one of the founders of JCC Kraków, is a figure of legendary proportions. A prominent lawyer and professor at the Jagiellonian University, she survived the Shoah in Kraków. She later joined Solidarity and worked as an editor of an underground anti-communist newspaper; she is also a women's rights advocate and a great friend of Ukraine.

In an exclusive interview for the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), she talks with Marharyta Ormotsadze about JCC Kraków's support for Ukrainians and her experience of fighting for life and freedom under the Nazi and Communist regimes in Poland.

Marharyta Ormotsadze (M.O.): JCC Kraków has been providing great material and moral support to Ukrainians since the first day of the Russian-Ukrainian war. As one of the founders of the Jewish community in Kraków, are you doing anything personally to support Ukraine?

Zofia Radzikowska (Z.R.): JCC Kraków has been helping Ukrainians a lot. Personally, I have participated in raising money, and my son twice donated a large package of clothes and other items to the Center. I also shut down haters of Ukraine on Facebook if that counts as help.

M.O.: Could you describe your impressions of what is happening in Ukraine in more detail? Given your life experience, why should people support and care about Ukraine?

Z.R.: I believe that the Ruscists are committing crimes against humanity in Ukraine and are using the same words as Hitler did with reference to the Jews, depriving them of their right to exist. The world must support Ukraine and stop the orcs so they wouldn't try to attack other countries. And crimes must be punished!

M.O.: How do you see Poland's role in the lives of Ukrainian refugees?

Z.R.: Most Poles and the state itself support and accept Ukrainians. However, some listen to Russian propaganda. I used to think that everyone understood what propaganda was. For example, in Poland, Russian propaganda says that we should remember the events in Volhynia and that refugees enjoy some privileges in Poland over Polish citizens.

M.O.: What is your answer to those Jews who find it difficult to sympathize with Ukrainians because of the Shoah?

Z.R.: I explain to Jews that Putin denies Ukraine any right to exist, just as Hitler did to the Jews, and he is even using the same words. The president of Ukraine is an ethnic Jew.

M.O.: Why did Russia start this terrible war against Ukraine?

Z.R.: Russia is a monster. They are not Europeans but murderers, orcs. People there are slaves; they do not understand what a free person is. They were slaves, who produced other slaves. I heard Putler's speech before the war. He spoke on television in front of the whole world and disowned Ukrainians, just as Hitler once disowned Jews. Putler is totally like Hitler.

I believe there is only one way out for the world: the international community must partition Russia.

About the Shoah in Kraków

On the eve of World War II, more than 3.3 million Jews lived in Poland. Almost 90% of them were killed in the Shoah, which means "catastrophe" in Hebrew. This mass extermination of innocent people by the Nazi regime based on Jewishness alone is referred to in the non-Jewish world using the Greek word Holocaust, which means "complete burnt offering."

Many Jews do not use this Greek designation but rather say "Shoah." Radzikowska, who lost her father in Auschwitz, also refers to the tragedy of European Jewry as Shoah.

M.O.: Do you remember life in Kraków before the Shoah?

Z.R.: I was born in Kraków in 1935 into a Jewish family. We did not live in the Jewish district of Kazimierz, but downtown, on Krupnicza Street near Planty Park. My father, Yitzhak Melcer, was a furrier and had his own workshop. My mother, Sara Melcer, worked in a dental supply store. We had a good life.

M.O.: What were the relations between Poles and Jews before 1939?

Z.R.: Even though I was a child then, I believe that relations between Jews and Poles were quite good. My mother had many acquaintances who were clients, both Jews and non-Jews, just dentists. She was not the owner of the shop. The owner went to Australia before the war and left her everything. Thanks to Polish acquaintances, my mother was able to save some of our possessions during the Shoah.

M.O.: Do you remember the first days of World War II?

Z.R.: Germany attacked Poland on 1 September 1939 at 4 a.m. This is similar to how the Russians launched their attack on Ukraine at 4 a.m.

When Germany came to Kraków in 1939, the Germans took everything from us. But my mother asked some Polish friends to take the goods [from the store] and some possessions and keep them for her. After the war, she was even able to get some of the goods back.

I remember that someone from the then Kraków government visited us. My father told us we had to leave our apartment. As I understand it, we were in a good situation because the army took our building. An officer came and gave my father two full weeks to evacuate.

I remember when people came and took everything from our apartment. The last thing they took was my little bicycle. I had never used that bike. The whole apartment was empty. It was a very unpleasant situation.

I saw my grandfather for the last time. His name was Wowk, and he came with my aunt. My other aunt managed to escape to the east, and they were taken by the Russians in Lviv and sent further eastwards. My aunt survived there, in Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan; they returned to Poland in 1946.

My mother managed to obtain several Polish documents with Polish names. She changed her name to Józefa Litefka. Using these documents, we were able to find a room in what was then a suburb of Kraków and lived there.

My father could not be with me because he was in the same circumstances as all Jews in Poland. With good documents, we women could pass ourselves off as Polish Christians. But my father could not fake it well because of the circumcision. So, he found another place to live; we did not know where exactly. We met him twice before the Kraków ghetto was set up.

M.O.: Could you please explain why the Kraków Jews went into the ghetto but your family did not?

Z.R.: They [the Nazis] set up a ghetto for Jews in 1941. My parents made up their minds then. My father decided to go into the ghetto because the old Jews told us to go there. At that time, no one was afraid of the ghetto and understood it as something different. You see, this was our history. There were always ghettos in old cities in Poland and other European countries. A ghetto was a special place for Jews, a Jewish neighborhood. The first ghetto was created in Rome thousands of years ago. It was not a place for killing, but for living outside of Polish society, in the Jewish community. No one realized that it would be something different in 1941. People were afraid of the Bolsheviks, not of the ghetto.

However, possessing intuition and courage, my mother decided that she and I would stay on the street. We looked good. I was a blonde. We spoke Polish well. We went to church, the same church that everyone else in the village attended.

All this was not of much help because a policeman once showed up at our door late at night. He knew that we were Jews, and he was going to take us to the Gestapo. It was 1942 or 1943. Eventually, my mother gave the policeman some jewelry, which was what he came for. After a while, he returned with the same story. He even took my baby blanket, saying that his children needed it.

M.O.: Did you realize that the blackmailer would return?

Z.R.: Yes. After his second visit, my mother was ready to flee. She realized that we had to run away. She found a room in another place, in Nowa Huta, then a village and now a district of Kraków. In any case, I even went to school there.

We lived in Nowa Huta until 1945 when the Red Army came. Of course, the Soviet army pushed the Germans out and liberated us. We no longer had to hide.

M.O.: What happened to your father Yitzhak?

Z.R.: After the war, I believed that my father would return. My mother looked for him in all institutions. Then some people came to my mother and told her that my father was killed in Auschwitz.

After that, I studied the history of the Kraków ghetto. The ghetto in Kraków was liquidated in 1943. People who could work were sent to the Płaszów camp, which was liquidated in 1944. And the last transport from Płaszów was to Auschwitz. My father was probably in that transport.

My mother told me that my father was not coming back, and we no longer had to wait for him.

M.O.: What happened to your mother after that?

Z.R.: After a while, my mother met a man who came from the Polish army. He was from Lviv and had lost his family there. The Russians took him to the east, and his family stayed back in Lviv and was killed. He served in the Red Army and then in the Polish Army. He fell in love with my mother and adopted me as his daughter. We had a complete family again; my brother Adam was born in 1950.

Postwar period

M.O.: What happened to Jews in Kraków immediately after World War II?

Z.R.: Some people returned to Kraków from where they had been hiding. A total of 946 people returned from the USSR. So, there were various groups of survivors in Kraków but no unified organization. These were religious gatherings dedicated to Shabbat and Jewish holidays. We held meetings in Kazimierz for Purim, Passover, and other celebrations in the Remah Synagogue. (It is one of the oldest synagogues in Poland and one of the ten synagogues that survived the Shoah in the Kazimierz district of Kraków. — Author)

In 1950, the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland was established as a minority organization that was supposed to work under the supervision of the Minister of International Affairs.

It was only after the fall of the communist regime that the Association of the Children of the Holocaust was created. This is not a very good name, because what happened was not the Holocaust but the Shoah. It is called Shoah in Hebrew. The Holocaust is a rather wrong understanding of what happened.

We had many meetings, and as eyewitnesses of the Shoah, we had to speak about what happened. Only then did I become a member of the kehillah, the Jewish community in Kraków. I became a believer, but not in the orthodox sense of Judaism. I went through a conservative bat mitzvah (an initiation ritual for Jewish girls. — Author), during which I read the Torah in the Tempel Synagogue (a conservative synagogue in Kraków. — Author).

M.O.: How did your life develop after the war?

Z.R.: During the war, I was a Catholic. Like all children, I took it all seriously. But my mother was a wise woman. She sent me to a Hebrew school in Kraków. It was a Tarbut school, a Zionist rather than a religious institution. After a week, I left the church and abandoned religion. I run away from any religion. At school, we studied the Tanakh, and it was like a cheder, a traditional religious school that had taught Jewish children for centuries. But we didn't understand a word of it. We were children from non-religious families that survived the Shoah. When one of us began to protest against learning the Tanakh, the teacher said: "You don't have to believe, but you have to know it."

And here I am, a child, saying to myself: "Okay, I don't have to believe in this. I don't have to believe in any God." So, I became an atheist very quickly. Can you imagine that? After one week at school!

I studied at this school for only two years, but it was enough. I like the sentiments of the Zionists and the feeling of being proud — never afraid — of my Jewishness. That's why I decided to go to Eretz Yisrael. We also had an organization called Hashomer Hatzair for young scouts, like Jewish socialists. These were Zionist socialists. We were all scouts and all ready to go to Eretz.

M.O.: Why did you stay in Poland?

Z.R.: Two years later, the school was closed. It was 1950, the peak of Stalinism. The communist government of Poland had already severed relations with Israel, and all who called themselves Zionists were enemies to them. And our school was closed as a Zionist institution.

Many Jewish schools survived, especially in Lower Silesia, but not my school. In any case, two years were enough for me — they formed me for life. Then I asked my parents for a passport for Israel. In those days, our passports were kept by the police.

M.O.: Why were your passports in the hands of the police?

Z.R.: It was a communist country, not an independent country, but a state dependent on the Soviet Union. It was Stalin's period. Police officers decided who could get a passport and who could not. My father was denied. I don't know why we were denied. They say it was because of the country's security. I don't know how our passports could possibly contradict the Communist Party.

I went to a regular school, then to university. My life developed, and I did not emigrate anymore. I have my university and my friends.

M.O.: How did you choose your profession?

Z.R.: Initially, I studied Oriental philology. I studied it only because a friend of mine was in this major. I graduated from the philology department and then pursued a law degree. I finished my doctorate, which was very serious work for me. I didn't flirt with the doctorate.

After graduation, I was an academic teacher for more than 30 years. I taught criminal law and logic at the Jagiellonian University. Of all the events in those years, it is important to mention that I survived in March 1968.

The Soviet antisemitic campaign of 1968

M.O.: In March 1968, there was an antisemitic campaign in Soviet Poland. How were you able to avoid being harmed?

Z.R.: It happened after the Six-Day War in Israel in 1967, when Israel defeated the armies of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, and other countries that were friends of the USSR. At that time, all communist countries associated with the Soviet Union began to sever diplomatic relations with Israel. Communist propaganda claimed that Israel was the aggressor. In reality, however, the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Algeria formed a military coalition and began to block Israel. (Just like now Russian propaganda claims that Ukraine is the aggressor, but in reality, Russia is attacking Ukraine. — Author)

Although the Polish communists had no connection with Israel, the pro-Soviet government of Poland said that Polish Jews were to blame. They wrote that Poles had only one homeland, and if Jews wanted to go to Israel, let them go. Suddenly every Jew was issued a passport!

It happened for the first time in 1956 when Poland asked to remove all Jews from the army, police, and government. In 1968, history repeated itself. The procedure was very humiliating. It was a one-way ticket. The government provided a very limited list of things you could take with you. But I said it was my country and my place. Who was to say that I had to go somewhere else?

I was already working at the Jagiellonian University, and no one was mistreated there. I was working on my doctoral dissertation, got married, and was already following the family path. I didn't want to leave Poland.

M.O.: What was happening to Polish society?

Z.R.: There was terrible anti-Israeli propaganda. Also, at that time, students rebelled all over Europe: in France, Germany, everywhere. They rose up against the bourgeoisie. We also rebelled but did so against censorship.

Let me tell you a story from that time. A theater in Warsaw staged Adam Mickiewicz's Dziady (Forefathers' Eve). Dziady is a very ancient funeral rite when people bring something to the grave and eat it there. For the East, it was quite a political issue, because it is a story about an underground organization of students at Vilnius University and how they were persecuted. There were a lot of bad things about the tsar in Dziady. It was crazy: the Soviet ambassador protested against the staging of this play. The theater was forced to withdraw it, and in response, students in Poland protested.

M.O.: How did the strikes go?

Z.R.: Students took to the streets. All university cities were on strike. In Warsaw, the strike began on 8 March, and in Kraków on 20 March. The Jagiellonian University was also on strike. I was already employed there as a researcher.

The strike ended when the police came with tear gas and dispersed the students, and arrests followed. For three more days, walking in Planty, Kraków's central park, was impossible because of the tear gas sprayed in the air.

The police also came to our department, asking where we were during the strikes. In the entire law department of the Jagiellonian University, they asked only two people — those with Jewish surnames, Professor Waldenberg and me. I was at my workplace, and the students confirmed that this was true. I had an alibi. Professor Waldenberg was at a conference near Kraków. So, no one was charged in Kraków.

However, there were places in Poland where students went on strike, and the strikes did not end well. In Warsaw and Katowice, people lost their jobs, especially in the editorial offices of magazines and universities. Many thought they had to leave the country, and brilliant intellectuals emigrated. A total of 20,000 people left Poland. I believe Poland lost a lot because of this exodus.

M.O.: When did you become a member of Solidarity, and what was the most important thing you learned from your experience in this organization?

Z.R.: It was 1980. It was a very warm time around the New Year just like now. And then came the terrible winter. Solidarity was born during a strike. Lublin was first, followed by Gdansk and other cities. A third of the Polish Communist Party became members of Solidarity.

I edited an underground newspaper. It was my way of fighting. Hope came to Poland. We had elections in 1989, and I came to Israel for the first time.

We don't know for sure, but the USSR apparently wanted to put this counterrevolution in order. Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany. But Poland decided that we did not need the Russians. We decided that we would fight.

Likewise, Ukraine has chosen to fight. In this struggle, we are on your side and believe in your victory.

Marharyta Ormotsadze

Marharyta Ormotsadze is a co-founder/producer of the Word of the Righteous project, which tells about the valor of Ukrainians who saved Jews throughout Ukraine during the Holocaust.