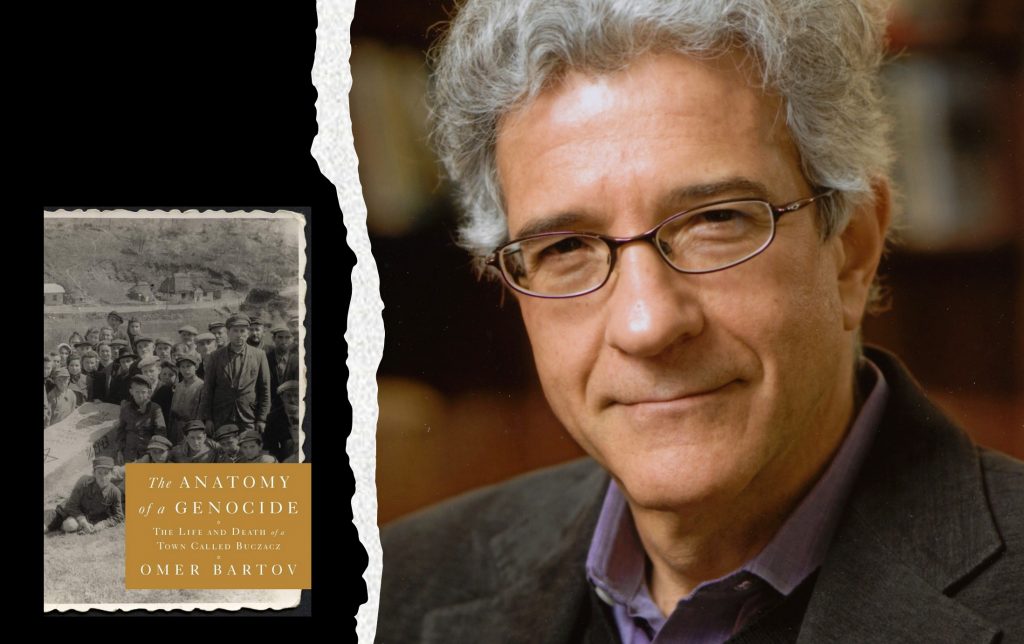

Omer Bartov: “I feel a particular responsibility for understanding the history of the Jewish people"

Professor Bartov, please tell us what influenced your choice of the profession of historian? What personal factors and people contributed to your choosing research topics?

I have been interested in history since my youth, possibly because of my own origins. I was born and raised in Israel, a country in which history is not merely a question of personal interest but also of political import; and while I am entirely secular, I feel a particular responsibility toward understanding the history of the Jewish people, especially in its complex and often bloody encounter with modernity and nationalism.

“I have been interested in history since my youth, possibly because of my own origins.”

As a historian I was influenced by a number of my mentors: Professor Saul Friedländer at Tel Aviv University, and Dr. Tim Mason at Oxford University, were especially influential. But I have also been influenced by non-academics, such as my father, Hanoch Bartov, who was a well-known writer and journalist in Israel, and Ilona Karmel, an author and educator in the United States and a survivor of the Holocaust born and raised in Kraków.

Which historical works were most important for you in the process of becoming a historian? Which historians made the greatest impact on your formation as a professional historian?

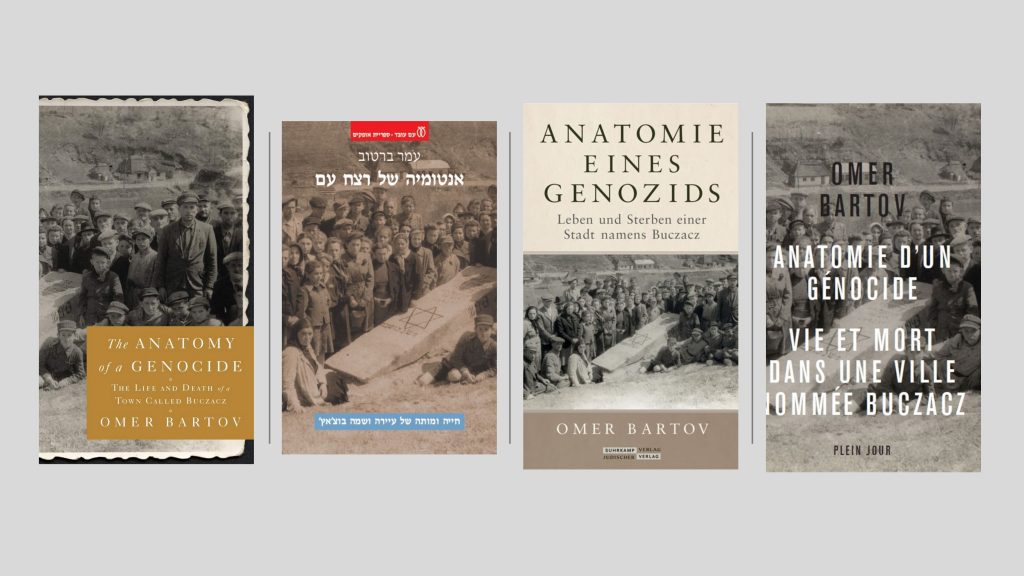

I became interested earlier on in what was called “history from below,” first in my research on the German Wehrmacht’s involvement in war crimes on the Eastern Front of World War II, which I investigated from the perspective of combat soldiers and junior officers (in the books The Eastern Front and Hitler’s Army), and most recently in my study of the town of Buchach [Buczacz] in eastern Galicia/West Ukraine (Anatomy of a Genocide). This last study also indicated my interest in longue durée history, spanning several centuries, and my interest in local history, i.e. focusing closely on events in one town. In-between I have also written books that could be characterized as intellectual history and history of representation, such as my studies of the links between industrial warfare and genocide in the two world wars and their representation, and in my study of the recycling of antisemitic imagery in 20th-century cinema (The “Jew” in Cinema). Finally, I have also written extensively on history and memory, as in my study of the politics of memory in West Ukraine in my book Erased, but also in essays on history and memory in Germany, France, and Israel (see, e.g., my books Mirrors of Destruction, Murder in Our Midst, and Germany’s War and the Holocaust). In writing on these topics, I was obviously influenced by numerous scholars and other writers, too many to detail here. I’ll only mention Lutz Niethammer on history from below; Christian Streit and Hannes Heer on crimes of the Wehrmacht; Lawrence Langer and Geoffrey Hartman on testimony and memory; Saul Friedlander on integrated history and on representation; the essays of Primo Levi, especially in The Drowned and the Saved; Tim Mason’s work on the relationship between politics and ideology; and many, many others.

How would you characterize the American academic world?

This is a huge question. The gist of it is that in my field of history, American academe is highly professionalized. Having received my undergraduate training in Israel and PhD from Oxford, and having taught initially in Israel, I can say that in comparison, on the undergraduate level, the American system is more focused on a general education, whereas, on the graduate level, it provides rigorous training. It is less interested in intellectual matters that go beyond academe. It does have a tendency toward fads and fashions. But it is also unique in that it is more open-minded than other academic systems I know (history departments have many professors teaching non-US and indeed also non-European history) and is very much focused on increasing gender and ethnic diversity despite the general atmosphere in the country in recent years. It also adheres to rules and regulations, objective standards, and fair evaluations to a larger extent than most other systems I am familiar with, partly thanks to its vast size and partly because of a regular and rigorous inter-institutional evaluation system.

At present, you are working at Brown University. How would you describe the current intellectual milieu there?

Brown is a highly competitive, liberal, private university. Intellectually it is very open-minded. If there is a bias at Brown, I would say that it is a bias against bias and prejudice. This may appear at times like political correctness, but generally speaking, Brown encourages professors to teach what they want and how they want to teach it. I assume that if there were students or professors who expressed particularly biased views that would cause an uproar, but in truth, this rarely happens. To be sure, the university needs to constantly examine itself, particularly at these times of growing political and intellectual radicalization. Up to now, it has withstood the test, I believe.

“The notion of passive bystanders or observers has to be revised.”

What trends in the development of modern world historiography of the Holocaust do you consider to be the most important?

There are several. From my own point of view, reflecting my research, the growing focus on local history/microhistory and on first-person history/testimony appear to me to be the most important. There is, however, also an opposite and similarly important trend, which is to contextualize the Holocaust within the larger history of colonialism, imperialism, racism, and genocide. Finally, there is also a growing interest in studying the Holocaust through the prism of environmental history, historical geography, and digital humanities, for instance, by trying to create interactive mappings of events (e.g. Jewish concentrations in Budapest or roundup in Italy) and writing histories in this vein (such as work by Tim Cole).

Since the 1990s there has been an increasingly greater focus in international Holocaust studies on so-called “bystanders.” What important methodological changes took place in assessing these roles of “passive bystanders” during the genocide?

I think that generally, the trend has been to realize that the notion of passive bystanders or observers has to be revised. This can be seen from a number of perspectives. It has been shown, for instance, that the public in Germany both knew more about the events of the Holocaust and profited from them with material goods (see, e.g., work on Hamburg, and studies by Götz Aly). It has also been shown that much of the killing of Jews was not secret but public, and therefore entailed large numbers of observers who could choose to act in one way or another. Additionally, it has been shown that the transition from being a rescuer, to a passive bystander, to a profiteer, and finally to a collaborator, was not as dramatic as we would like to think. In investigating events in one town, as I have in the case of Buchach, it is clear that there were practically no “bystanders” in the sense of people who simply stood by and did nothing. People might shelter victims, but then also denounce them; express abhorrence of the killing, but then take over the property of the victims; participate in rounding up or killing victims, but also shelter some of them, at times for reasons of greed or exploitation, at times because of pangs of conscience. Since the killing was public and within earshot and often sight of the population, the whole notion of bystanders in this context must be dismissed.

How is the role of economic factors in the implementation of the Holocaust defined today?

From the state level, it is pretty clear by now that the Holocaust was a profitable undertaking: the German state and its agencies took over properties, bank accounts, and other material and financial assets from the victims (or initially those expelled) on a vast scale. The victims also provided free labor on a vast scale; the entire SS economic venture during the war, which was vast, was based on a seemingly inexhaustible supply of slave labor. But also, on the local level, genocide proved to be profitable. Eastern Europe is dotted with villages and towns in which people live to this day in property taken over from Jews who were murdered.

How does contemporary world historiography evaluate the structural and institutional factors in the organization of the Holocaust?

If I understand this question correctly, it has to do with contextualizing the implementation of the Holocaust within the larger historiography of the modern world. Generally, one can say that the Holocaust was an extreme manifestation of the kind of violence produced by a combination of factors, most prominent among which is imperialism and colonialism, the marriage between racism and science, technological warfare and the perfection of industrial killing, the mobilization of politics of fear and resentment, stoking up old prejudices, both social and religious, and the modern pursuit of “final solutions.” In this sense, the Holocaust can be seen in the context of other genocides, going back to the Herero in German Southwest Africa in 1904 and the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915; to murderous colonial exploitation such as in King Leopold’s Congo; to scientific racism and eugenics as developed in the US, Britain, and Germany; and to the new mass politics as exercised in pre-1914 Vienna and the rise of modern antisemitism in German in the 1870s. At the same time, the Holocaust had its own unique features, such as deportations over vast territories (similar to Soviet policies) and extermination camps (unprecedented and still unique).

How would you assess the development of the historiography of the Holocaust in Ukraine today? Which directions do you consider the most promising for Ukrainian researchers?

I am not aware of major contributions to Holocaust research by contemporary Ukrainian researchers. I know of work being done on Ukrainian policemen, which can be very valuable; one past research that was done on Ukrainian rescuers, which is useful. Similarly, there has been some work on statistics and demography. But as far as I know, the best work by scholars of Ukrainian extraction is done outside the country, such as e.g., John-Paul Himka. There is of course work by non-Ukrainians which is very valuable, e.g., by Karel Berkhoff, Wendy Lower, Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe, etc. I also believe there are very few useful publications on the Holocaust in Ukrainian, either by Ukrainian scholars or translated into Ukrainian.

In characterizing the events of the Holocausts in the Eastern European lands, you propose defining them as “communal genocide.” Please explain briefly what you include in this term.

What I mean by this term is that in the context of such genocides as the Holocaust, there is a local dynamic of relations between the different religious and ethnic groups inhabiting a locality that plays into the manner in which genocide is perpetrated by the external force coming to the region. This dynamic is not merely the result of war, violence, and occupation during the Holocaust itself but also of relations built up over a long period of time between the local populations. In the case of Buchach, for instance, this means that resentments and prejudices, national aspirations and past struggles, as well as previous occupations (Russian in WWI, Soviet in 1939-41), were triggered once the Germans arrived on the scene in July 1941. The Germans used this to their advantage, transforming the local Ukrainian militia into an auxiliary police unit and employing it to assist them in murdering the Jews. This militia had already engaged in anti-Jewish, anti-Polish, and anti-Soviet actions before the Germans arrived and in the early weeks of the occupation. But some of the violence that takes place under German rule has nothing to do with German policies, such as the ethnic cleansing of Poles by Ukrainian militias in 1944.

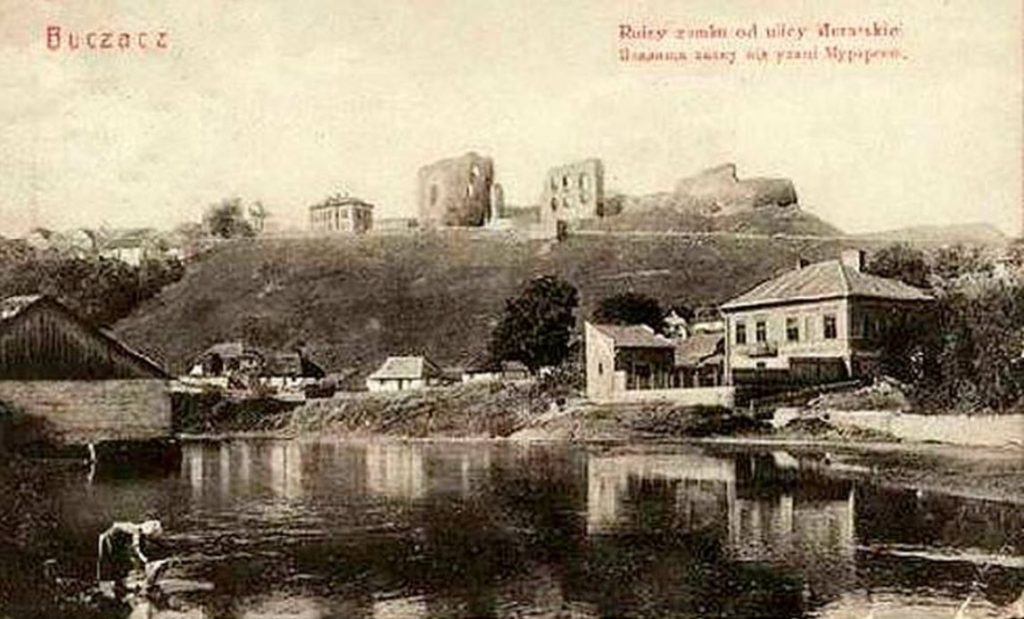

In your book Anatomy of a Genocide, you did a deep analysis of the historical preconditions that preceded the Holocaust in Buchach. What were the trends in the sphere of inter-ethnic relations that had developed in the city over the centuries?

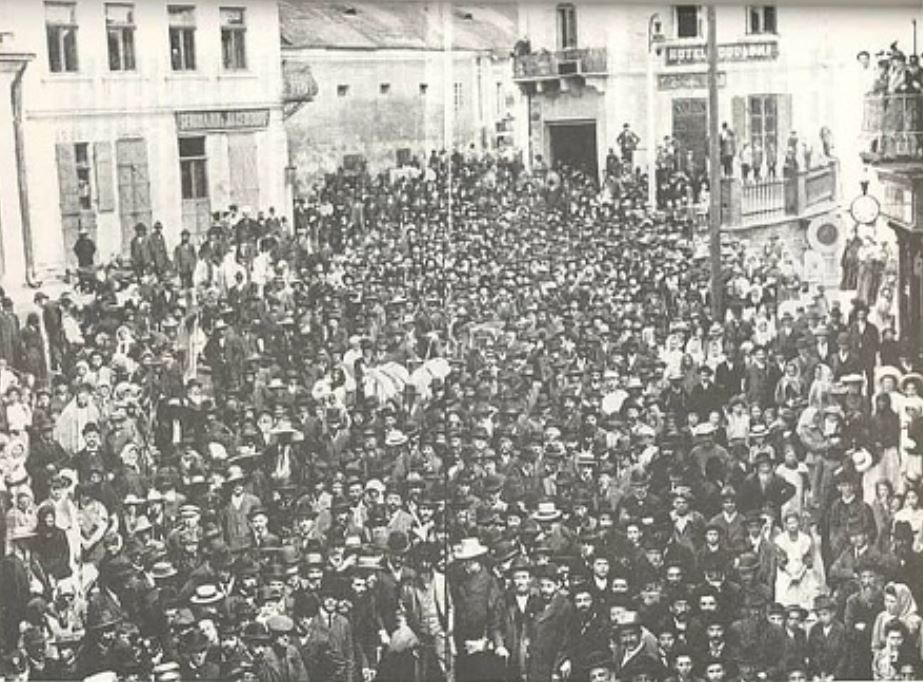

I’d say that Buchach (Buczacz in Polish) is pretty typical of other towns of its size in Galicia, having a mixed population (Jews being the majority or plurality since at least the late 19th century, Poles the second largest group, and Ruthenians/Ukrainians the majority in the surrounding countryside, with a large Polish representation and far fewer Jews). Within Jewish history, Buchach is notable in that it was not a Hassidic town; its last Hassidic rabbi “reigned” in the first half of the 19th century. Unlike the almost strictly Hassidic Chortkiv (Czortków) nearby, Buchach was largely made up of Mitnagedim (non-Hassidic Orthodox Jews) and Maskilim (adherents of the Jewish Enlightenment) and a growing minority of Zionists on the eve of WWI, which greatly increased in the 1920s-30s. But the internal dynamics between the three populations were similar. Possibly, relations in Buchach were somewhat better than in other towns, although that is not certain and the reasons for this are not entirely clear. There were some friendly Polish villages around where Jews found shelter in WWII. The Basilian Monastery and its abbot were also opposed to anti-Jewish violence, as were some of the old Ukrainian elites. On the other hand, these same elites got along very well with the Germans. While there was local anti-Jewish violence in July 1941 by young Ukrainians, some of whom can be traced back to the interwar OUN, it was not as extensive as, e.g., in Zolochiv (Złoczów) and Sambir (Sambor). But again, generally speaking, Buchach is quite representative of other towns of similar size in the region.

How would you characterize inter-ethnic relations in Buchach during the period of the ZUNR? What changes took place after this small city was incorporated into the Second Rzeczpospolita?

I have just published one of the most detailed (but highly biased) accounts of Ukrainian rule in this period in my new book, Voices on War and Genocide. This account by the Polish headmaster Antoni Siewiński is a rare insider’s look into these events. Generally, the impression is that there was a fair amount of violence against Jews under Ukrainian rule. Of course, there was also Polish anti-Jewish violence, not so much in Buchach but as we know in Lwów (Lviv). It would appear that both Poles and Ukrainians resented the attempt by Jews to stay out of the fray and to maintain a neutral position; at the same time, as Siewiński stresses, local Christians also resented the fact that Jews tried to conform to whichever state was in charge – Polish, Ukrainian, or before that, Austrian or Russian, and viewed this as an example of cowardice and conformism, rather than as a survival strategy. All this played into local attitudes once the town came under Polish rule and in the interwar period, and the radicalization of Ukrainian nationalism, as well as its violent suppression by the Polish authorities, had an additional negative effect on attitudes by both sides toward the Jews, quite apart from the economic situation that led to competition between local Jews and the new Ukrainian cooperatives.

How did the period of Sovietization between 1939 and 1941 affect the course of inter-ethnic relations in Buchach?

This is a major question that my book deals with. Generally, all three groups are victimized by the Soviets through deportations and incarceration. The Poles are targeted first and also have most to lose since the Polish state has been dismantled. Ukrainians and Jews partly welcomed the Soviets because of their growing animosity toward the Polish state. But then the Jews are targeted for social and political reasons. Proportionately Jews are deported at a higher rate than either Poles (second highest) or Ukrainians (lowest rate). But in retrospect, for Jews, deportation was a blessing since almost all those who were not deported were murdered by the Germans. Ukrainians are targeted last and, as we know, are then executed in large numbers when the Soviets withdraw upon the German invasion. In Buchach, Polish testimonies present the Poles as the main victims of the Soviets and Jews and Ukrainians as having collaborated with them. Ukrainians speak of themselves as having been the main victims and of Poles and especially Jews of having collaborated with the Soviets. Jews are more ambivalent about Soviet rule because, in retrospect, it was not as bad as German rule and because under the Soviets, Jews had greater education and administrative opportunities than under Polish rule. But Ukrainian and Polish resentment against the perceived role of Jews in their own victimization feeds into anti-Jewish violence under the Germans.

What were the key features of the implementation of the Nazis’ Holocaust policy in Buchach?

Buchach is again quite similar in this respect to other towns in the region. The important elements to emphasize here include:

- Apart from one mass killing of the “intelligentsia” in summer 1941, mass killing begins in earnest only in the fall of 1942.

- The first roundups in the fall of 1942 involve transports to Bełżec and gassing there.

- The killings in the first half of 1943 are in situ on two hills next to the town, in public view. There are no more deportations to Bełżec, which has been closed. Over half the Jewish population is killed where they live or nearby.

- Buchach, like the rest of Galicia, is declared Judenrein in June 1943. But hunting down Jews persists until the final (second) occupation of Buchach by the Red Army in July 1944.

- The mass killing of Jews in Buchach (10,000), in the Buchach-Chortkiv region generally (60,000), and in Galicia as a whole (250,000) could not have been accomplished so quickly and efficiently without the massive presence of Ukrainian auxiliary police units, local Ukrainian police posts, and Jewish policemen. In the Buchach-Chortkiv region, 20 German security policemen kill 60,000 Jews – obviously, the rounding up is done by their helpers.

- As noted above, these are public killings from the beginning, so everyone can see, and nothing is secret.

- As also noted above, the Christian residents of Buchach immediately make use of Jewish property of those killed if not confiscated first by the Germans.

How do you define the role of the local population in the dynamics of the Holocaust in the city? What factors defined the specific features of its behavior?

I have responded to much of this already above. Generally, one should differentiate between Poles, who soon find themselves also under threat from Ukrainian nationalists, and Ukrainians. In terms of rescue, it was more likely to be helped by Poles than by Ukrainians, but the general situation is that Jews are either refused shelter or given shelter and sooner or later driven out, denounced, or killed by the people sheltering them. There are, of course, some noble exceptions. The attitude of Ukrainian nationalist leaders and many others is that the Jews have to go one way or the other. The reasons for actual participation in the killing vary. Some young men join the police for monetary gain, some in order to evade being sent for labor in Germany, and some, later on, to avoid having to join the SS-Division “Galicia.” There appears to be also ideological conviction and general dislike of Jews. The ability to get hold of Jewish money and property is key. It should be remembered that after the Judenrein of June 1943, much of the killing of Jews is done by Ukrainian policemen in villages and shelters that the Germans are reluctant to enter and are not familiar with. There is little sense of regret about the disappearance of the Jews. Here I recommend reading Ukrainian gymnasium teacher Viktor Petrykevych’s diary, which I just published in the book Voices on War and Genocide mentioned above.

How did the Ukrainian-Polish conflict of 1943–1944 affect the fate of the Jews who were still alive?

It appears that the ethnic cleansing of Poles in 1944 makes it more likely for Poles to shelter Jews since they too now feel threatened. On the other hand, the mayhem in the region generally gives license to everyone to participate in violence, so there is much evidence of bandits and villagers attacking Jews in the remaining German-run agricultural labor camps or in hideouts. Again, most of the Jews killed in spring-summer 1944 appear to have been killed not by the Germans but by local elements.

What trends in the culture of memory about Holocaust victims on the territory of the countries of Eastern and East-Central Europe would you single out?

First is the recognition of the Holocaust in those countries as a separate event from “anti-fascism” and “collaboration” in the aftermath of the fall of communism. This led both to a new historiography, and to new attempts at commemoration, restoration, and preservation of Jewish sites, especially in Poland. Second, simultaneously but increasingly more pervasive in recent years, is a “competition of memories” between two traumas, or the so-called “double genocide” argument, namely, that while the Jews were murdered by the Nazis with the help of some local “bad apples,” the locals (nashi) were victimized by the Soviets with the help of, or synonymous to the Jews. The changes from one post-communist narrative to another can clearly be seen in Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia… Ukraine is somewhat different, first because of the regional difference between West Ukraine, where the glorification of OUN-UPA began early, whereas commemoration of Jewish sites was and remains very limited, and the rest of Ukraine, where there is less love lost for the collaborationist nationalists in the west, and a greater adherence to the old Soviet line, although that appears to be changing somewhat currently.

Has anything changed in the culture of memory about the victims of the Holocaust in Ukraine since the publication of your monograph Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine?

I believe there have been changes in West Ukraine, though they are rather limited and rarely on the initiative of the local authorities. In Buchach, for instance, the Jewish cemetery has now been surrounded by a wall and is thus better protected from vandalism. That has happened only very recently – when I was last there in 2016, that had not yet happened. But this was done by volunteers from Israel and funded by them. Additionally, since 2016 a bust of the author and Nobel Prize laureate Agnon stands in front of his presumed home in Buchach, next to a small cultural center, but that too was on the initiative of a young Ukrainian and former Buchach resident, funded by outside sources, and initially reportedly met by resistance from the mayor. In other sites, there have been similar development, combining local and foreign volunteers and outside funds, such as the restoration of the long-neglected choral synagogue in Drohobych (Drohobycz). Conversely, public sources have been used to fund museums and statues dedicated to Ukrainian freedom fighters associated with OUN, such as Bandera statutes. Many other sites remain in a state of total neglect and lack of recognition. Mass burial sites remain unmarked. This is the case in Buchach (on Fedir Hill) and elsewhere, unless (as in Chortkiv) outside initiatives have taken care to mark them. One indicative site is the fort at Zolochiv, which contains a museum for the Ukrainian victims of the Soviets but makes no mention of the mass killing of Jews there by local residents in July 1941.

In your opinion, what does Ukraine need to do in order to achieve reconciliation around the tragic pages of the Second World War?

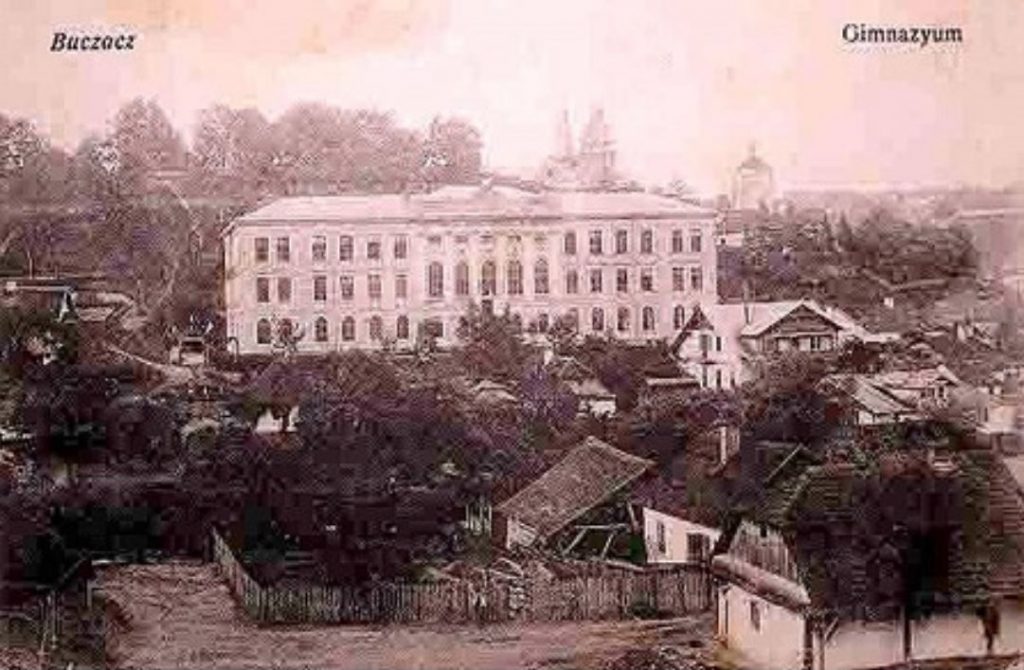

The most important step would be education. For instance, I was told in 2016 that in the famous gymnasium in Buchach, which was attended by major figures in Jewish, Polish, and Ukrainian history, students learn nothing about the Jewish and Polish past of their town and their school. One of the most important educational initiatives in Germany took place in the 1970s-80s when small towns began to investigate their own past, to discover their former Jewish residents, and to uncover the more difficult stories of how they were treated by their neighbors and local authorities, and how those complicit in these actions never paid a price for their crimes. This kind of local initiative, working with young people who would undertake such local research, would make a vast difference. I would also include marking places where Jews and Poles had lived, where Jews were killed and buried, and so forth (e.g., the Jewish cemetery in Zhovkva/Żółkiev serves as a marketplace, as does the site of the old Jewish cemetery in Lviv). Second, one needs to enhance school and university education on Jewish history in Ukraine as well as on the Holocaust – not generally but rather specifically in Ukraine. Third, a government-sponsored major commemoration site and museum would make a vast difference. As I know from my own involvement in the initiative to create a memorial museum at the site of Babyn Yar (Babi Yar), the initiative was funded by a private individual rather than government or municipal sources and has recently been taken over by elements that seem to want to turn it into something very far from the original purpose, for which reason both I and others who supported the initiative have stepped aside. Had the Ukrainian government and the municipality of Kyiv initiated the construction of such a project, that would signal a changed attitude at the top.

Omer Bartov is the John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History at Brown University. He directed the project “Borderlands: Ethnicity, Identity, and Violence in the Shatter-zone of Empires Since 1848,” in 2003-2007, and the project “Israel-Palestine: Lands and Peoples,” in 2015-2018, both at Brown’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, where he is Faculty Fellow. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Bartov was the recipient of fellowships from the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies at the Hebrew University, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the National Endowment of the Humanities, the American Academy in Berlin, the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, among others. His book Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, won the 2018 National Jewish Book, the Zócalo Book Award, the Ab Imperio Award, and the Yad Vashem International Book Prize for Holocaust Research. He has published eight monographs, including Hitler’s Army (1991), Mirrors of Destruction (2000), Germany’s War and the Holocaust (2003), The “Jew” in Cinema (2005), and Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine (2007). His edited volumes include Shatterzone of Empires (2013), Voices on War and Genocide: Three Accounts of the World Wars in a Galician Town (2020), and Israel/Palestine: Lands and Peoples (2021). Bartov has just completed a new book titled Tales from the Borderlands: Making and Unmaking the Past and is in the initial stages of a new project on “Remaking the Past: Israel, A Personal Political History.”

Omer Bartov is the John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History at Brown University. He directed the project “Borderlands: Ethnicity, Identity, and Violence in the Shatter-zone of Empires Since 1848,” in 2003-2007, and the project “Israel-Palestine: Lands and Peoples,” in 2015-2018, both at Brown’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, where he is Faculty Fellow. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Bartov was the recipient of fellowships from the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies at the Hebrew University, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the National Endowment of the Humanities, the American Academy in Berlin, the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, among others. His book Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, won the 2018 National Jewish Book, the Zócalo Book Award, the Ab Imperio Award, and the Yad Vashem International Book Prize for Holocaust Research. He has published eight monographs, including Hitler’s Army (1991), Mirrors of Destruction (2000), Germany’s War and the Holocaust (2003), The “Jew” in Cinema (2005), and Erased: Vanishing Traces of Jewish Galicia in Present-Day Ukraine (2007). His edited volumes include Shatterzone of Empires (2013), Voices on War and Genocide: Three Accounts of the World Wars in a Galician Town (2020), and Israel/Palestine: Lands and Peoples (2021). Bartov has just completed a new book titled Tales from the Borderlands: Making and Unmaking the Past and is in the initial stages of a new project on “Remaking the Past: Israel, A Personal Political History.”

[Editor’s note: The Buchach Gymnasium is a state educational institution opened in Buchach on January 10, 1899. Today it is the Volodymyr Hnatiuk Gymnasium in Buchach.]

Interviewed by Petro Dolhanov, Ukraina Moderna.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.