Our people on their currency: Eight natives of Ukraine depicted on Israeli banknotes

The State of Israel was created and built by Jewish settlers who came mainly from Eastern Europe. Among them were quite a few natives of Ukraine, especially from central (Dnipro) Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire.

Some of them entered the new state’s pantheon of heroes, even though people in their homeland know barely anything about them. We will tell you about the Jews from Ukrainian territories who were awarded one of Israel’s highest honors: their portraits depicted on banknotes and coins.

The predecessor of Israel’s current monetary unit, the shekel, was the Israeli pound, or the Israeli lira, which was introduced in 1952. In over half a century three different series of banknotes appeared with depictions of ornaments, landscapes, and images of the country’s residents.

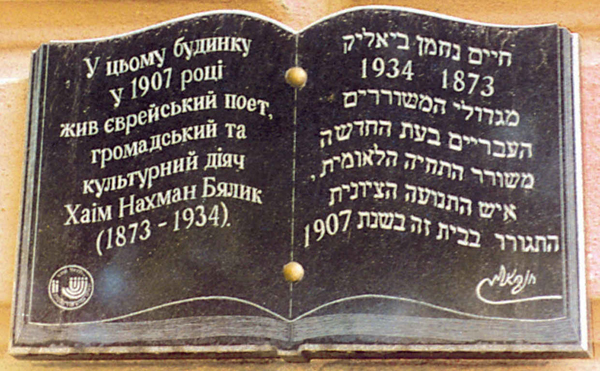

The National Bank redesigned the currency in the late 1960s. The four new banknotes depicted the portraits of distinguished representatives of the Jewish people. One of them was a native of Ukraine, the poet Hayim Nahman Bialik.

Bialik was born in 1873 in the village of Ivnytsia, in Volyn Gubernia (today: Zhytomyr oblast). The poet spent his childhood and youth in his father’s home in Zhytomyr, where he got married at the age of twenty. But he was formed as a writer and member of the Zionist movement in Odesa, where he lived, with short breaks, for over two decades.

Bialik is known above all for his Hebrew-language works. The poet’s life coincided with the restoration of this ancient language, which for a long period of time was considered exclusively as a bookish, “dead” language. In addition to writing poetry, Bialik translated classics of world literature into Hebrew.

During Bolshevik rule Hebrew was outlawed. In 1921 the Soviet government closed the Odesa-based publishing house Moriiah, which was co-founded by Bialik. That year he left the country for good.

After heading first to Berlin, he soon settled down in Palestine. The poet died in 1934. The Hayim Nahman Bialik Museum was created in his Tel Aviv house, and his portrait was featured on the 10-pound banknote.

n 1969 the Israeli parliament passed a law abolishing the pound and introducing a new currency. It decided to call the new money shekels, in honor of the ancient unit of weight of gold and silver and the Jewish rebels who minted their own coins in the 1st century A.D. Eleven years passed before the law was finally implemented.

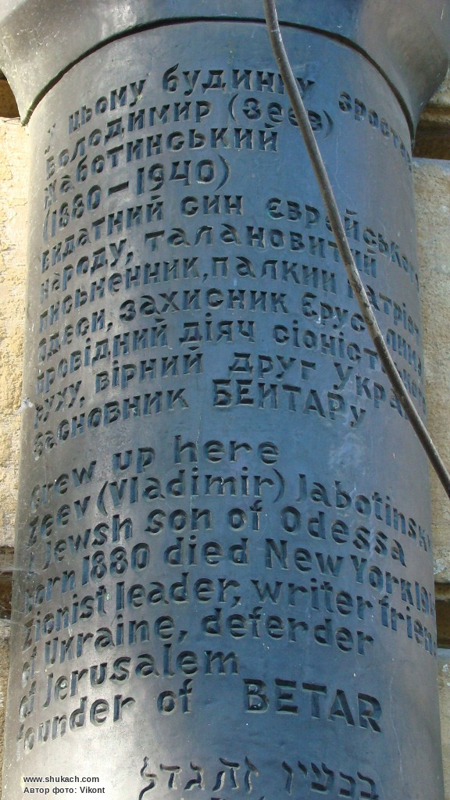

The 100-banknote from 1980 depicts another native of Ukraine, Vladimir (Volodymyr) Ze’ev Jabotinsky from Odesa.

At the beginning of the twentieth century he gained renown as a talented journalist and writer. In 1903 a new wave of anti-Jewish pogroms erupted in the southern part of the Russian Empire, and Jabotinsky joined the Jewish self-defense and Zionist movements.

Thereafter he devoted his life to the struggle to create Jewish armed forces and a Jewish state. However, he did not abandon his literary and essayistic work, and published a novel entitled The Five, about a Jewish family in Odesa.

It was impossible for Jabotinsky not to cross paths with his contemporary (and fellow countryman, to some extent), Bialik, one of whose poems Jabotinsky translated from the Hebrew into Russian.

Vladimir Jabotinsky did not live to see the founding of the independent Jewish state; he died in the U.S. in 1940. However, his ideas and practical activities played a considerable role in Israel’s founding.

Structures that were created under the influence of Jabotinsky’s ideas, like the Betar youth movement and the Likud Party, still exist in Israel to this day.

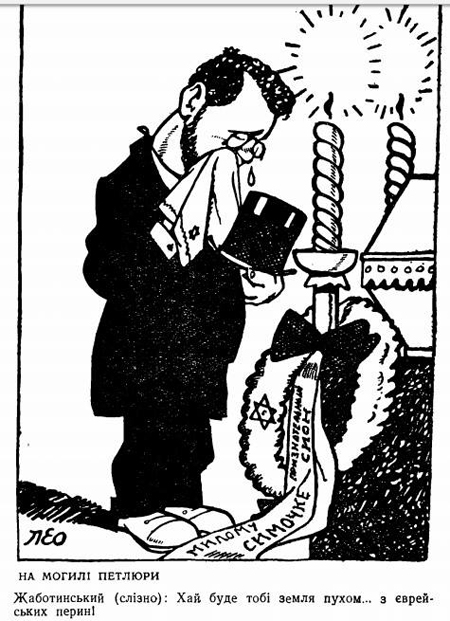

In our country Jabotinsky is remembered above all for his friendly attitude to the Ukrainian political movement of his day and the Ukrainian language. In particular, he expressed support for Symon Petliura, denying that he was an antisemite and a perpetrator of pogroms.

From 1982 to 1984 larger-denomination banknotes—from 500 to 10,000 shekels—were introduced.

The 5,000-shekel banknote pictures the fourth prime minister of Israel, Levi Eshkol (1895–1969). He was born in the town of Orativ, in Kyiv Gubernia, today’s Vinnytsia oblast.

After completing his education in Vilnius, the eighteen-year-old Levi immigrated to Palestine. During the First World War the young man fought in the ranks of the Jewish Legion of the British army, which Jabotinsky had helped form.

In the State of Israel the native of Orativ headed the defense and finance ministries. In 1963, when the legendary David Ben-Gurion stepped down as prime minister, he was replaced by Levi Eshkol.

It was Eshkol who spearheaded the solemn reburial of the remains of Ze’ev Jabotinsky in Israel’s national cemetery on Mount Herzl. Buried nearby is the head of the government, who died in 1969, while he was still in office.

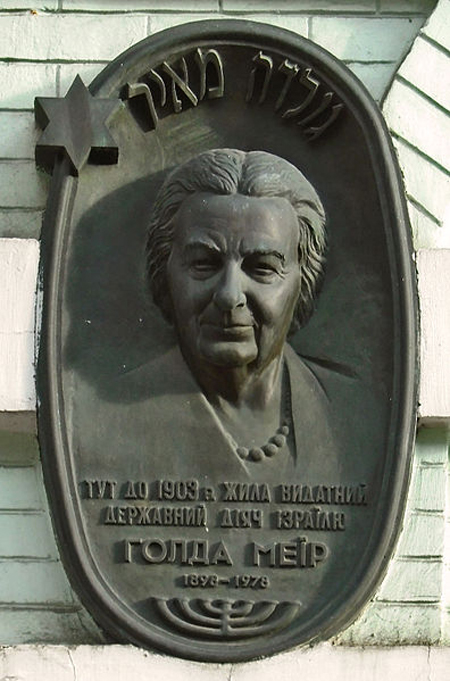

Eshkol’s successor was Golda Meir, whose portrait appears on the 10,000-shekel banknote of the same series.

The most famous female politician (née Mabovitch) in Israel was born into a poor Jewish family. Her father was born in Ukraine, and her mother—in Pinsk. Her parents met in this Belarusian city, where they resided for some time. Eventually, seeking a better life for themselves, they moved to Kyiv, where Golda was born on Baseina Street. The future prime minister’s first memory is connected with this Ukrainian city.

“I was then probably three and a half or four years old. We were living in Kyiv at the time, in a small apartment on the first floor. I clearly remember a conversation about a pogrom that was about to crash down on us.

Of course, at the time I didn’t know what a pogrom was, but I already knew that it was somehow connected to the fact that we were Jews and that a crowd of riffraff with knives and staves are walking around the city and shouting: ‘They crucified Christ!’ They are looking for Jews, and they will do something horrible to me and my family. Then I stand on the stairs leading to the second floor, where another Jewish family lives; their daughter and I hold each other’s hands, and we watch our daddies trying to barricade the front doors with boards.

The pogrom did not take place, but to this day I remember how terribly frightened I was,” wrote Golda Meir in her memoirs. She recalled this episode during her audience with Pope Paul VI in 1973.

The other things connected with Kyiv which remained lodged in Meir’s memory are hunger and poverty. In 1903, when she was five years old, the family returned to Pinsk, and her father left for the US. Three years later, after saving up some money, he brought his family over. Golda Meir never stepped foot in Kyiv again.

Unlike Jabotinsky, Meir considered Symon Petliura as the main culprit behind the anti-Jewish pogroms in 1918–1920 in Ukraine, which she mentions in her book, My Life.

In 1985 the Israeli government introduced the new Israeli shekel at a ratio of 1000: 1. Since then the shekel is distinguished as the “old” and “new.” The design of the largest-denomination old banknotes (especially the ones portraying Levi Eshkol and Golda Meir) remained practically unchanged; the sole difference being that three zeroes were removed.

Larger-denomination banknotes were also introduced. This series, which remained in circulation until the year 2000, is the “most Ukrainian one”—five out of seven portraits.

The obverse side of the 20-shekel bill bears the image of the first Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second Prime Minister of Israel Moshe Sharett.

The politician’s father was Ya‘akov Shertok. In 1881, when another round of pogroms began, he left Russia for Palestine, but returned five years later and settled in Odesa. He married Fanny Lev from Mykolaiv, and the couple moved to Kherson, where Moshe was born.

Ya‘akov was known as a political commentator and Zionist activist. In 1906 he saved himself from the pogroms a second time by going to Palestine, now with his family, including twelve-year-old Moshe. This time he remained for good in the Promised Land.

Like the majority of the founding fathers of the nation of Israel, Moshe Shertok (he changed his surname after the proclamation of independence), devoted many decades of his life to helping the Jews gain statehood. Owing to his good education, fluency in eight languages, oratorical talent, and personal charisma, he served as a negotiator and intermediary.

Sharett is not considered one of the most successful prime ministers. He lasted in his post only two years and lost to his predecessor and opponent, David Ben-Gurion. Nevertheless, this native of Kherson is regarded as the founder of Israeli diplomacy.

His participation in the signing of the Declaration of Independence also went down in history. The background of Sharett’s portrait shows another important event in the history of the newly created state: the solemn raising of the Israeli flag at the United Nations building in New York in 1949.

The obverse side of the banknote shows an image of the most famous school in Israel, the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium in Tel Aviv, from which Moshe Sharett graduated. The building was designed by Joseph Barsky, who moved here from Odesa in 1907.

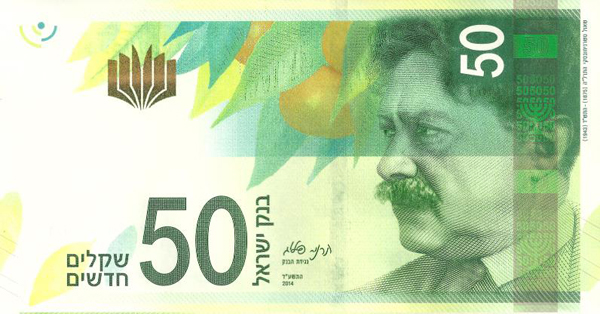

The 50-shekel banknote has already been mentioned in an earlier article published in Istorychna pravda. The designer was Israeli artist Eliezer Weishoff, whose other work (a postage stamp) unexpectedly sparked the interest of the Soviet Ukrainian KGB.

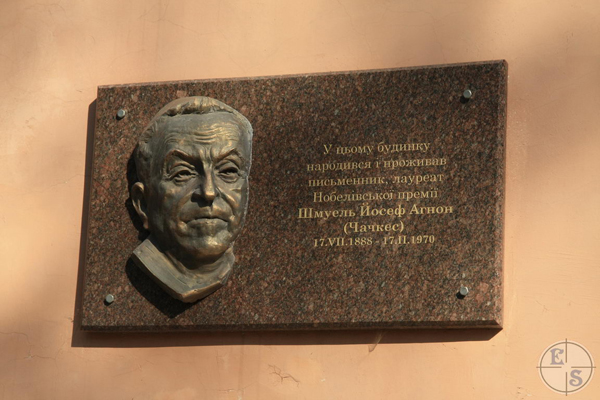

Unlike the other heroes showcased in this article, the writer Shmuel Yosef Agnon (formerly Czaczkes), who is depicted on this banknote, was not a native of the Russian Empire but Austro-Hungary. He was born in Buchach (today: Ternopil oblast), and his father was from Chortkiv

For about a year Agnon lived in Lviv, from where the nineteen-year-old immigrated to Palestine. The writer returned to Galicia (now under Polish rule) two times.

Ukrainian was one of the languages in which Agnon was fluent since childhood. Several of his short stories have Ukrainian themes.

The year 1966 was a triumphant one for both Agnon and Israeli literature. He became the first—and thus far the only—representative of the country to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The second president of Israel Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, formerly Isaak Shismshelevich from Poltava, is depicted on the 100-shekel banknote. He studied at the Poltava Gymnasium and Kyiv University.

In Poltava in the early 1900s Shimshelevich engaged in the same kind of activities as his contemporary, Jabotinsky, in Odesa. He built up the Jewish political movement and organized anti-pogrom defense forces.

In 1906 the police found weapons earmarked for the Jewish self-defense force in the young man’s apartment in Poltava. His family was arrested, but Isaak escaped and soon ended up in Palestine, where his forty-year-long path to achieving statehood began.

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi’s wife and colleague, Rachel Yanait (née Golda Lishanska) was also from Ukraine, from Malyn (today: Zhytomyr oblast).

The first series of the new Israeli shekel also included coins bearing the portraits of Levi Eshkol (5 shekels, 1990) and Golda Meir (10 shekels, 1995).

The next redesign of the Israeli currency took place in 1999. Four types of banknotes were issued, three of which depict portraits of Ukrainian Jews: Moshe Sharett from Kherson (20 shekels), the Galician Shmuel Yosef Agnon (50 shekels), and the Poltava native Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (100 shekels).

A novel feature of this series is the vertical orientation of the images. In 2008 the same shekels were reissued—but in plastic, not paper.

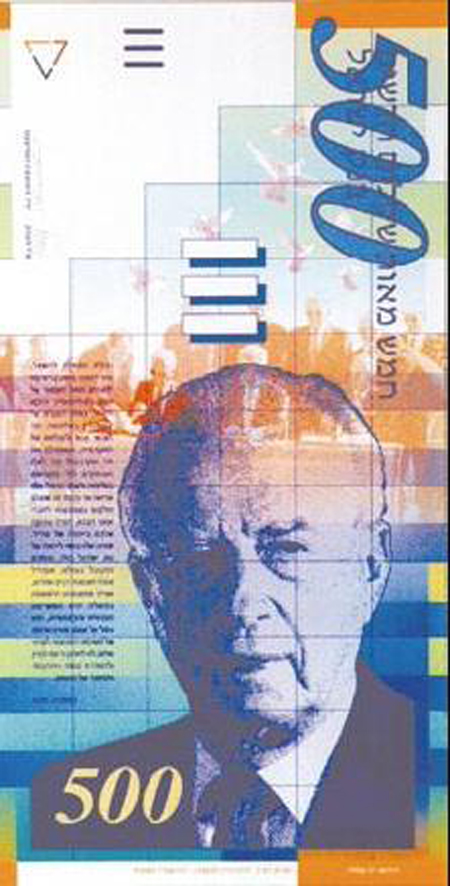

There was also a design in the works for a 500-shekel bill featuring a portrait of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, whose father was born in the village of Sydorovychi (today: Kyiv oblast). However, it was never introduced into circulation.

Rabin, who was assassinated by a fanatic in 1995, was one of the individuals whose image was slated to appear on the next series of banknotes. However, a decision was ultimately made to “depoliticize” the currency.

In 2013 the public learned that poets writing in Hebrew and Yiddish would be featured on all four of the new banknotes (to be circulated in tandem with the preceding series).

One of the writers thus honored was Saul Tchernichowsky (1875–1943). a native of Mykhailivka (today: Zaporizhia oblast).

Tchernichowsky was a doctor in Melitopol, Kharkiv Gubernia, and Odesa. He began writing poems in his childhood, and later translated classics ranging from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Byron into Hebrew.

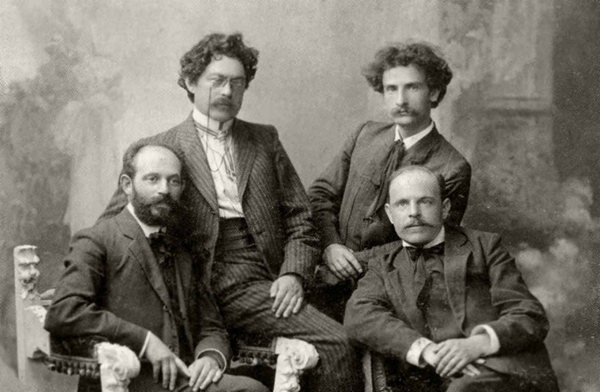

Living in Odesa in the early twentieth century and writing poetry in Hebrew, Tchernichowsky inevitably became acquainted with another hero featured in this article: Hayim Nahman Bialik.

Like Bialik, Tchernichowsky moved from Soviet Odesa to Berlin, where a year later, in 1922, he moved to Erets Israel.

In memory of Bialik, the Tel Aviv authorities established a prize in his name for writers working in Hebrew. Both Agnon and Tchernichowsky were two-time laureates.

The 20-shekel banknote in this series features a portrait of the poetess Rachel Bluwstein. She was born in the Russian city of Saratov (also known as Viatka), but she spent her childhood in her father’s homeland of Poltava, where she became acquainted with the writer Volodymyr Korolenko. Her mother was the daughter of a Kyiv rabbi. After finishing school, the young poetess studied painting in Kyiv.

After moving to Palestine, Bluwstein traveled to the Russian Empire to visit her relatives in 1914. However, the First World War broke out and she was able to return home only five years later.

During the war she lived in Berdiansk, Saratov, and Odesa. She taught Jewish refugee children, wrote poetry, and did translations.

Thus, out of the total number of distinguished representatives of the Jewish people whose images grace Israel’s currency, eight of them were born on the territory of today’s Ukraine.

09.01.2019

Eduard Andriushchenko

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

Istorychna Pravda’s ‘Shalom!’ media project, which explores the Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue, is made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.