Righteous Among the Nations from Kyiv

We continue our series of publications dedicated to the Righteous Among the Nations in the Ukrainian cities affected by the ongoing Russian invasion. This time, we look at the city of Kyiv.

Over the past month, the Ukrainian capital has been the target of some of the most vicious attacks since the full-scale war broke out on February 24, 2022. Russian missiles and drones hit residential and office buildings, ordinary homes, playgrounds, etc. Critical infrastructure facilities have been partly damaged, causing Kyiv residents to go for hours without electricity and water.

Among the Kyivites that heroically stay in the capital in these difficult days are dozens of families of the Righteous Among the Nations recognized by Yad Vashem and the State of Israel. There are five living Righteous Among the Nations among Kyivites: Vasyl Nazarenko, Oksana Antipchuk (née Deineko), Nina Bogorad, Lidia Savchuk, and Valentina Sokolova (Poloz). In the spring of 2022, Savchuk was evacuated to Europe personally by Mikhail Brodsky, the Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the State of Israel to Ukraine. Other families refused to leave as of October 2022, deciding to stay in Kyiv due to their advanced age.

Unfortunately, there are no living Righteous Among the Nations who saved Jews in German-occupied Kyiv. Nazarenko, Savchuk, Bogorad, and their families rescued Jews in the Vinnytsia region, while Antipchuk and Sokolova helped them in the Zhytomyr region.

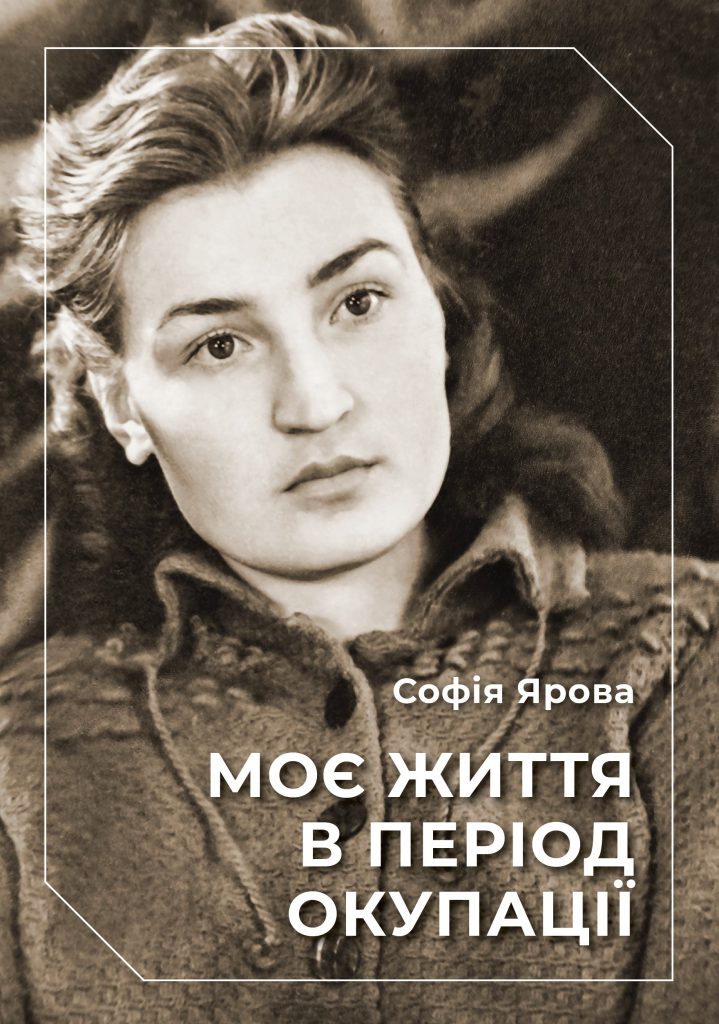

Sofia Yarova

The Holocaust in Kyiv began with the tragedy of Babyn Yar. The Germans ordered the entire Jewish population to come to the corner of Melnykova Street and Dehtiarivska Street (near the cemetery) with documents and personal belongings on September 29.

Sofia Yarova recalls the September 29, 1941events in her memoirs. She was the last surviving Righteous Among the Nations who saved the Jews doomed to death in Babyn Yar. Yarova headed the Association of the Righteous of Babyn Yar and did many things to commemorate and help heroic families. Her grandson defends the Ukrainian land from the Russian invaders today.

Together with her mother, Yefrosinia Boiko, Yarova saved seven Jews in the Ukrainian capital and thus recalled the events of September 1941 in her memoirs:

"Everyone was sure that the Jews would be sent to Palestine. Everything was calm; there were no worries. Our neighbor Syoma Barash, a student from Kharkiv, went [to Babyn Yar]. He came to his parents but didn't find them as they had already left. He had cerebral palsy but was able to walk on his own. We asked him to stay, but he wanted to go to Palestine.

By noon, we already knew that the Jews were being shot. Thousands of Kyivites rushed to rescue and hide those Jews who had escaped or had not yet left. Now, remembering those days, I am amazed at our Soviet people, their humanity, rich souls, and highest morality. Aware they could be shot on the spot, they still helped, saved, and hid [the Jews]. This is what they call courage nowadays. But this was not courage. We were brought up that way. It was the standard of conduct for a Soviet person. How many acquaintances and strangers my mother saved! And I was next to her.

It so happened that Petro Khomenko, my uncle on my mother's side, ended up not in the Darnytsia camp but in Hasivka in Kyiv. On September 29, 1941, the inmates of precisely this camp were sent to bury the Jews shot in Babyn Yar. I remember with horror the stories my uncle told and his condition in those days. As he said, it was an unimaginable burden for a normal person's mind. The earth breathed. It was hard for a normal person to see a baby being snatched from the mother's arms and thrown into a pit where many were still alive. Later, the uncle cut his leg with the edge of a can in the camp and was not taken [to Babyn Yar] the next day. The Germans and our policemen let Ukrainians go for bribes if they had papers certifying they were not Jews or communists. Two weeks later, we took a sick person home. My uncle, a handsome man two meters tall, could not recover from what he saw there and very soon died of rapidly progressing tuberculosis.

On October 12, 1941, our Jewish neighbor Semen Lipnitskiy, whom we called Uncle Syoma, came to our yard. We were friends with his family, which included Aunt Tanya, daughter Maika aged 12, and two-year-old son Alik. We gathered at our place, of course. I clearly remember our large expandable table and 12 neighbors sitting around it, including Bondarenko and Uncle Syoma. He was in a soldier's uniform as he had escaped from captivity. As I already wrote, my mother knew how to predict and solve all problems. The neighbors went home, aware of the joint decision that Uncle Syoma would leave at 7 o'clock and would try to cross the Dnipro. At 8 p.m., all the neighbors were told that Syoma had left. And they heaved a sigh of relief: everyone wanted to live... In reality, however, Uncle Syoma never left. Mom changed him into dad's clothes, and he spent the night at our place. In the morning, my mother took him to a secret crossing. We did not see him again, but his family was informed in 1944 that the Soviet soldier Semen Lipnitskiy had died as a hero."

Below is Yarova's autobiography in English. It was translated into Ukrainian and published in 2022 by the Word of the Righteous project with the support of the Ukrainian World Foundation (Ukrainian Canadian Congress) and the VAAD of Ukraine. The Ukrainian-language text is available on the website of the Institute of History of Ukraine, the National Academy of Sciences, or here. The memoirs are published at Yarova's personal request.

The Yarovy family was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations in 1997. Sofia Yarova passed away on September 29, 2020, on the anniversary of the Babyn Yar tragedy. She was the last living Righteous Among the Nations who saved Jews in Kyiv. There are a total of 266 Righteous Among the Nations from Kyiv, according to Yad Vashem and the Jewish Confederation of Ukraine.

The Glagolevs and Yegorychevs

The Glagolevs are one of the most famous families from Kyiv recognized as the Righteous Among the Nations. Their patriarch Aleksandr Glagolev was a priest, polyglot, and rector of the Kyiv Theological Seminary. He stopped pogroms in pre-revolutionary Kyiv and, despite numerous invitations to Europe, remained in Ukraine after the revolution. Shot by NKVD men during the Great Terror period, he is known to the whole world as priest Alexander from Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The White Guard. Glagolev was a family friend and spiritual mentor of the writer.

There are nine Righteous Among the Nations among Glagolev's children and their families. His son Aleksey Glagolev, his wife Tatiana Glagoleva, and their children Nikolai and Magdalina saved many families from death in Babyn Yar. His daughter-in-law Maria Glagoleva (née Yegorycheva), the wife of the officer Sergey Glagolev, worked together with her mother Aleksandra, sisters Tatiana and Klavdia, and uncle Grigoriy Maslennikov to shelter Jews in Kyiv.

Zoya, the daughter of Maria and Sergey Glagolev, told in an interview for the Word of the Righteous film that, starting from September 29, 1941, Jewish friends began to come to the Yegorychevs' apartment on Desiatynna Street in Kyiv, asking for help. This continued throughout the occupation period. "To whom, if not to you, should we go?" asked the Kyiv Jews.

Aleksey Glagolev was ordained before the war and served in the Intercession Church in Podil. One of the first things he did early into the German occupation of Ukraine was to refuse to pray for Hitler. The Germans beat him for this, but he survived. He described the events of the Holocaust in Kyiv in the text "For my friends." The title is a quote from the Gospel: "Greater love has no one than this, than to lay down one's life for his friends" (John 15:13).

"On September 28, 1941, an order was issued that '...all the Jews of the city of Kyiv had to come to the corner of Dehtiarivska Street near the Jewish cemetery by 8 a.m. on September 29.'

The German authorities told them to bring along valuables and warm clothes and announced that not only Jews who disobeyed this order but also all persons who dared to hide them would be shot. Terror gripped the hearts of people — not only those to whom this order directly applied but also all who preserved at least some human feeling.

No one knew what exactly awaited the Jews, but it was clear that nothing good was to be expected. The choice of the Jewish cemetery as the gathering place and the complete silence about any food supplies did not bode well. The Jews would sink into utter despair and then grasp at a straw like a drowning man, clinging to the faint hope that trains would be brought to the Jewish cemetery and take them somewhere out of the city.

Exile, hard work, and even a concentration camp — all this seemed [not] as terrible as violent death. Dum spiro, spero. (While I breathe, I hope.) As long as a person breathes, there is hope for escape from this bondage and the salvation of their own life and the lives of their children and loved ones.

The thought of going to the shooting yourself while also carrying or leading your children by the hand and then seeing how they are torn from their mother and killed before your eyes was so terrible that everyone chased it away as quickly as possible. That's why everyone wanted to believe that the Jews would face mere expulsion from the city, nothing else. But it was hard to believe, and this ominous uncertainty was so unbearably painful and terrible that a wild dying cry of people waiting for their death could be heard in all corners of the city.

After a terrible night came an even gloomier morning.

Following the German order, tens of thousands of Jews proceeded to the Jewish cemetery in a continuous stream. There were all kinds of people in this procession: healthy-looking young men and women; stooped elderly Jews; strong middle-aged men; weak, frightened women; children of all ages, and even babies.

Many were luxuriously dressed and had carters pulling whole heaps of expensive things. Looking more triumphant, others transported their things themselves on carts and baby strollers. Still, others carried all their belongings — on their shoulders and those of their small children. Yet another group led or carried their sick and crippled. These were overtaken by horse-drawn carriages in which the most famous Jewish professors, doctors, and lawyers from Kyiv made their last earthly journey.

And all these people flocked from different corners of the city in small streams to blend into one giant, endless river flowing towards the Jewish cemetery.

It was a stunning — indeed, soul-wrenching — sight!

What shall I do? How to prevent the evil that is brewing? These questions were racing through my tired mind. And then suddenly, a poor woman approached me through mutual acquaintances, begging me to save her and her child. It was Izabella Mirkina, the daughter of a famous Kyiv dentist.

She hoped that if I entered a plea for her before the mayor and testified that she was married to a Russian, she would not be required to follow the German order of September 28. I immediately wrote a letter, and my wife ran with it to the city council. We all hoped that the mayor would grant my request, believing the testimony of a son of the respected professor and priest Glagolev, in whose parish he was born and lived all his life. But nothing came of it. The then mayor, Professor Ogloblin, walked into the reception hall, pale and confused, and said that he could do nothing, unfortunately. The German authorities had told him that the Jewish question was a personal affair of the Germans and that the Ukrainian authorities had no right to interfere. It was impossible to speak to anyone from the German authorities as all the doors were tightly closed that day.

Having lost all hope of legalization, Izabella Mirkina rushed to catch up with her family and share their fate. However, she did not find her father, sister, or stepmother in the agreed place near the cemetery. Many others were not there, either. They had already passed the point of no return. As we learned later, more than 70,000 Jews were brutally shot in Babyn Yar behind the Jewish cemetery in a matter of days."

The Glagolevs and the Yegorychevs saved Izabella Mirkina and dozens of other Jews. Having a church seal in his possession, priest Aleksey Glagolev issued certificates of baptism with Russian and Ukrainian names to Jews. Moreover, all the employees in the Intercession Church — the psalmist, deacon, watchman, etc. — hid Jews. Many lives were saved.

Maria, the daughter of Aleksey and Tatiana Glagolyev, lives in Kyiv, as do the Shuranovs, the family of Maria Yegorycheva's granddaughter. The daughter of the Righteous Among the Nations Magdalina Palian has been evacuated to Germany.

Gudkova, Morozova, and others

The previous text about the Righteous Among the Nations from Mariupol and Kherson talked about Anastasiya Fomina. She fled to Kyiv from the Holodomor in the Donbas and worked as a nanny for the Kats family. In the fall of 1941, she saved their three-year-old Tsezar Katz from the death march to Babyn Yar and hid him for several weeks. Then, on the advice of friends, she took him to an orphanage and left him there with a note saying that his name was "Vasya Fomin."

The orphanage on Predslavynska Street was headed by Nina Gudkova. She took care of more than 50 orphans. Among them were Jewish boys, including Vasya Fomin (Tsezar Kats). Gudkova and the orphanage staff saved 12 Jewish children with their heroic efforts.

The Righteous Among the Nations Anna Morozova and her mother Yevdokia Mikhailova helped Maria Konstantinovskaya, a Jewish doctor from Kyiv, and her daughter Shelya escape certain death in Babyn Yar.

Shatel, a French girl who arrived in Kyiv as an orphan in the early 1900s, was adopted by her uncle, who named her Marta Mykhailovskaya. In October 1941, while already a widow, she and her daughter Maria saved the Jewish soldier Aleksandr Lysogorskiy. After the war, Lysogorskiy married Maria.

These are just a few of the hundreds of names.

Although Soviet and Russian propaganda reprimanded Ukrainians for their inaction during the Babyn Yar period, eyewitnesses of those terrible events confirm that most Kyivites rescued their Jewish friends and neighbors starting from September 29. For almost half a century, from 1941 to 1991, the silence of the Soviet authorities, which forbade any references to Babyn Yar, led to the loss of thousands of priceless rescue stories. However, even what we know today is a monument to humanity.

The exact opposite of humanity is the war Russia has unleashed against Ukraine. Babyn Yar has become one of the first targets of the terrible bombing. On March 3, 2022, three Russian missiles hit the television tower standing there and the surrounding area. At that moment, the present author was in her apartment across the street from Babyn Yar and felt the five-storied building shake as if from an earthquake. Black smoke rose from Babyn Yar after the hit, and the blast wave destroyed trees, lampposts, and public transport. On March 3, Russian missiles killed six more people there — ordinary citizens and a TV tower worker.

Marharyta Ormotsadze

Marharyta Ormotsadze is a co-founder/producer of the Word of the Righteous project, which tells about the valor of Ukrainians who saved Jews throughout Ukraine during the Holocaust.

All photos: Word of the Righteous and personal archives of the Righteous.

Read related articles:

Righteous Street: How Ukrainian cities honor the Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Street: How Ukrainian cities honor the Righteous Among the Nations (part 2)

Ukrainian Righteous Among the Nations and war: how the aggressor tries to erase history

Ukrainian Righteous: Ivano-Frankivsk

Ukrainian Righteous Among the Nations: Mariupol and Kherson

Translated from Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.