The “Struggle Against Cosmopolitanism” and “Zhdanovshchyna,” or repressions against Jews and Ukrainians

The historian Oley Bashan discusses repressions against Ukrainians and Jews in the second half of the 1940s and the early 1950s.

Andrei Kobalia: How did Ukrainian society perceive Jews in the 1930s and 1940s, during the Second World War, and in the first years after the war?

Oleh Bazhan: Ukrainians and Jews were on the same side of the barricades in the struggle against the Nazis during the Second World War. However, if we examine archival documents, then we can speak objectively that there were also manifestations of antisemitism on the everyday level. For example, we know that the danger of a pogrom in Kyiv emerged in 1946. The problem was that Jews started to return to their homes, but by that time they were already occupied by someone else. The state security organs monitored this situation and reported “upstairs” to the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party. Then these issues had to be resolved one way or another. But one cannot speak of total rejection and hatred.

Andriy Kobalia: What is the Zhdanov Doctrine and the struggle against cosmopolitanism? When did these two phenomena arise in the USSR?

Oleh Bazhan: First of all, it is necessary to explain that this ideology of “cosmopolitanism” means that importance is attributed to universal values, while national problems are of secondary importance. Using this concept as a point of departure, the then Soviet leadership launched its ideological and political campaign during the postwar years. It must be noted that this “struggle against cosmopolitanism,” the so-called “rootless cosmopolitanism,” took place during the second half of the 1940s, right after the Second World War. This large-scale campaign initiated by Stalin and his henchmen can be explained by a desire to restore Soviet order in the country, especially in the [former] occupied territories. For this it was necessary to find a kind of niche in the struggle against those who had supposedly not abandoned bourgeois ideology. The “struggle against cosmopolitanism” could best fulfill this role.

Oleh Bazhan: First of all, it is necessary to explain that this ideology of “cosmopolitanism” means that importance is attributed to universal values, while national problems are of secondary importance. Using this concept as a point of departure, the then Soviet leadership launched its ideological and political campaign during the postwar years. It must be noted that this “struggle against cosmopolitanism,” the so-called “rootless cosmopolitanism,” took place during the second half of the 1940s, right after the Second World War. This large-scale campaign initiated by Stalin and his henchmen can be explained by a desire to restore Soviet order in the country, especially in the [former] occupied territories. For this it was necessary to find a kind of niche in the struggle against those who had supposedly not abandoned bourgeois ideology. The “struggle against cosmopolitanism” could best fulfill this role.

[Andrei] Zhdanov, who was one of Stalin’s colleagues and the secretary for ideology, was ordered to launch a large-scale ideological campaign; hence the term “Zhdanovshchyna” [era of Zhdanov], a phenomenon that also took place in the history of Ukraine during the second half of the 1940s.

Andriy Kobalia: Tell us about the high-profile cases that are connected with these waves of repressions. For example, in the “struggle against cosmopolitanism.”

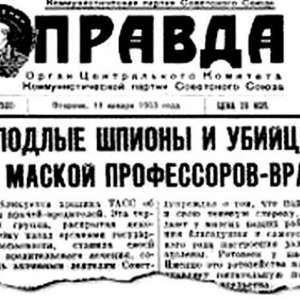

Oleh Bazhan: It is worth mentioning that the “struggle against cosmopolitanism” is superimposed on the situation that existed at the time in the USSR and the world. It should not be forgotten that from 1941 to 1943 Ukraine was under occupation. The Stalinist leadership was afraid that during this period something might have changed in the Ukrainians’ mentality. Therefore, it was necessary to carry out an ideological purge or a rebooting. As we mentioned earlier, the Soviet secret services monitored social moods, including those among Jews. They noticed the upsurge in feeling among Ukrainian Jews, who were very pleased by the rise of the State of Israel in the Middle East. Many people were eager to take part in building this state, or to help materially in creating these state institutions. Of course, this frightened Stalin. The “struggle against cosmopolitanism” was a broad ideological campaign. If we are talking about the peak of these repressive measures, this was the pogrom of the Jewish intelligentsia and the arrests connected with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which took place in 1948–1949. The reverberations of these events also reached Ukraine, and Jewish writers here were imprisoned. The peak was reached in the late 1940s–early 1950s.

Andriy Kobalia: A logical question arises. The idea of a struggle against cosmopolitanism contradicts the essence of the USSR. This idea of repression against the Jews contradicts the ideology of the USSR. It was convenient for the USSR to support the Jews and emphasize its negative attitude to the Nazis. Moreover, antisemitism was a holdover of the Romanov empire. And the USSR positioned itself as a state that condemned tsarism. And the idea of communism focused not on ethnic characteristics but on class issues. So, why did this campaign emerge, inasmuch as it contradicted the ideology of the [Soviet] state? Why this phenomenon?

Oleh Bazhan: The Land of the Soviets professed proletarian internationalism, and, of course, there were no overt manifestations of antisemitism here. But antisemitism can be traced throughout the entire history of the USSR. One can mention the policy of “war communism,” when an attack on the economic rights of Jewish artisans also took place. During the NEP period in the 1920s, the government often resolved the Jewish land question by violent means. Another good example is the repressions of the 1930s, the period of the Great Terror. At first glance we see that the repressions are developing along fifteen national lines. These are the Bulgarians, Poles, Germans, Greeks, Latvians, but we do not see the Jews.

However, when you analyze the statistics of the repressions of 1937–1938, the anti-Jewish repressions were concealed under the rubric of the “liquidation of bourgeois nationalist organizations.” There is a sentence there about the liquidation of Zionist organizations. There were also repressions against the Bund, the Mensheviks, the SRs, where the Jews were widely represented. The Jews thus accounted for the sixth largest number of victims during the repressions of 1937–1938, ceding their standing to Ukrainians, Poles, Russians, and Germans.

Andriy Kobalia: In other words, antisemitism already existed in the USSR and was directly linked to the Romanov period?

Oleh Bazhan: We can say that the Soviet Union assumed those negative features which existed during the Russian imperial era, when the government spearheaded the pogroms in the late nineteenth century, particularly in 1905–1907. During the Civil War period the Jews suffered at the hands of the White Guardists and the Red Army, and the army of the UNR [Ukrainian National Republic] in 1918–1919. Later, however, Soviet propaganda dumped everything on the UNR and the army of Symon Petliura. When the trial of Petliura’s assassin took place, the watchmaker Samuel Schwartzbard’s defense was based on the fact that this was supposedly revenge for the many Jewish pogroms, especially in 1919.

Andriy Kobalia: What was Stalin’s personal position on the Jews? I know that on 12 January 1931 he stated the following: “Antisemitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of antisemitism.” That is, in 1931 he declares that communists and citizens of the USSR cannot be antisemites. But what was his personal position?

Oleh Bazhan: Right now the Internet is rife with articles and discussions of whether Stalin was an antisemite. I would like to say that Stalin never openly and publicly declared his negative attitude to the Jews. However, he may have expressed this in private conversations. If you look at the memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev and his [Stalin’s] daughter S. Alliluyeva, they say that concealed antisemitism was characteristic of Stalin. During party meetings Stalin upheld the idea of proletarian internationalism.

Overt notes of antisemitism and repressions occur in the mid-1930s. First and foremost, he [Stalin] was engaged in a struggle with his political rivals, Trotsky, Kamenev, and Bukharin. But Stalin viewed them as rivals and did not focus on the ethnic aspect.

Andriy Kobalia: When we talk about “Zhdanovshchyna” and the “struggle against cosmopolitanism,” we mean dismissals from work, arrests, and possible deportation to other parts of the USSR. When Ukrainians and Jews were serving their sentences, were they able to contact each other?

Oleh Bazhan: If we examine dissident memoirs of the 1950s–1980s, we can state that contacts between the members of the Ukrainian and Jewish national movements did indeed take place. Yevhen Sverstiuk posed questions about why there were misunderstandings between the Jews and the Ukrainians in various periods. All these questions were raised. A cooling of these relations both in the camps and here in Ukraine was not observed. During party meetings in the 1960s, Petro Shelest, First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, even talked about a fusion of Ukrainian and Jewish nationalists and the danger [this posed] for the USSR.

Andriy Kobalia: Were convicted people amnestied after the deaths of the two leaders [Stalin and Zdanov]?

Oleh Bazhan: The repressions of the 1940s–1950s were not on the same scale as the repressions of the 1930s. “Rootless cosmopolitans” were threatened with dismissal from work, the government prevented people from engaging in creative activities, and in some cases this culminated in criminal cases and imprisonment. The people who suffered the most were those who were charged in connection with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee; these people were shot. One victim in Ukraine was the director of the Office for the Study of Jewish History and Culture, [Elye] Spivak. He died in prison. We did not see massive repressions in this period.

I would like to direct your attention to one detail. When I was working with archival documents I want to bring up the fact that during the “struggle against cosmopolitanism” it was not only Jews who suffered but Russians and Ukrainians as well. Stalin and his colleagues targeted both the Ukrainian and Jewish intelligentsia.

When we talk about “Zhdanovshchyna” and the attack on Ukrainian culture and the “vestiges of bourgeois nationalism,” we know that during this period, in addition to [the writers Yurii] Yanovsky and [Maksym] Rylsky, the well-known poet Andrii Malyshko also suffered. In 1946 he was the editor in chief of the journal Dnipro and the deputy head of the Union of Writers of Soviet Ukraine. He began to be hounded because he had made it possible for Yurii Yanovsky to be published on the pages [of his journal]—I mean his novel, Living Water—and M. Rylsky’s poem “A Word about My Mother.” The attacks came from critics of Jewish nationality. They set the tone of that plenum meeting of the Writer’s Union where Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich was present. These critics of Jewish background started to accuse Malyshko of supposedly paraphrasing the slogans of [writer] Mykola Khvylovy, who proclaimed “Away from Moscow!” and called for Russian writers to leave Kyiv as they can’t be in Ukraine if they are not Ukrainian writers. Andrii Samiilovych Malyshko denied all the accusations, but the repressions left a mark on his subsequent fate. Malyshko was not arrested, but he was dismissed from his post as deputy head of the Union of Writers of Soviet Ukraine, and, of course, he was stripped of his chief editor’s position at Dnipro.

Those same Jewish writers and literary critics themselves suffered during the period of the “battle with cosmopolitanism” and were repressed already in February 1949 for also not being ideologically correct and for supposed signs of anti-Sovietism.

Andriy Kobalia: But could these people return to their positions after Stalin’s death?

Oleh Bazhan: During the period of Khrushchev’s Thaw, the majority of those who had been repressed were rehabilitated. They were even allowed to publish their works. That is why it cannot be said that everyone lived with this label until the end of their lives. Incidentally, I would like to say that the “struggle against cosmopolitanism” was also aimed at the religious life of Jews. The disbandment of Jewish religious communities begins in the second half of the 1940s. Whereas in the second half of the 1940s there were approximately fifty-five synagogues, by the early 1950s this number had dropped to forty one. The case of the Lviv synagogue attracted much publicity. In their accusations against its members, state security officials claimed that this synagogue was acting as a transit point for Jews from the Baltic republics who wanted to reach the Middle East and the State of Israel. In fact, this led to the dismissal of the leaders of the community. An examination and analysis of documents reveal that Vilkhovyi, the commissioner for Religious Affairs under the Council of Ministers of the USSR for Ukraine, noted that these Jewish communities were engaging in functions that were not intrinsic to them. They were providing assistance to invalids, students, war veterans—to anyone suffering who needed it. The Jewish community of Lviv was helping Jewish families get settled after the war. This aroused displeasure on the part of the authorities and thus provoked a campaign.

Andriy Kobalia: We were talking with the historian Oleh Bazhan about the repressions against Ukrainians and Jews in the 1940s and 1950s. This has been the Encounters program with Andriy Kobalia at the microphone. This program was made possible by the Canadian non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. You have been listening to Hromadske Radio. Listen. Think.

This program is created with the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.