The crime of genocide in the history of Ukraine: Experience teaching a course at the University of Michigan

Reflecting on his experience teaching The Crime of Genocide in the History of Ukraine, an elective course at the University of Michigan, Yurii Kaparulin describes the structure of the course and how it incorporates the modern context of the Russian-Ukrainian war. He concludes with observations on interaction with American students and differences in curricula, sharing his general impressions.

When I was asked to develop and teach a course on Ukraine for American students, I had several ideas. It seemed to be a good opportunity to talk about Russia's current full-scale aggression against Ukraine — a war that has been going on for over a decade — and its background. At the same time, my historical and legal background suggested the need to clearly define the course's boundaries and identify a range of key issues around which to construct it. One of my primary goals was to deepen students' understanding of Ukraine and Ukrainians as a people and a nation. A short course on Ukrainian history could be useful here. Serhii Plokhy, Yaroslav Hrytsak, Timothy Snyder, Serhy Yekelchyk, and other colleagues have already created accessible and popular overviews of Ukrainian history that would perfectly fit my goals. However, I did not want to reduce teaching to retelling, so I included their publications in the list of recommended literature that students could refer to throughout the course.

I also considered adapting a course I had previously taught in Ukraine, History of the State and Law of Ukraine. However, it quickly became clear that this discipline was not typical in Western universities and belonged more to the academic tradition of Eastern Europe. Moreover, the chronological breadth of the course made it too general.

After reviewing the U-M College of Letters, Sciences, and Arts course catalog, I realized that the course title was key to attracting students' attention and successful recruitment. My course would be listed among electives, which included both classics, such as History of Ancient Philosophy, and courses like History of German Football, Anne Frank in Context, Ancient Law, The Legacy and Values of the US Air Force, Digital and Social Media, Video Games and Learning, Trauma and Mental Health in Postcolonial Africa, and hundreds more.

In view of this, I decided to create a customized course, combining my teaching and recent research, centered around Holocaust history, the crime of genocide, and other forms of mass violence.

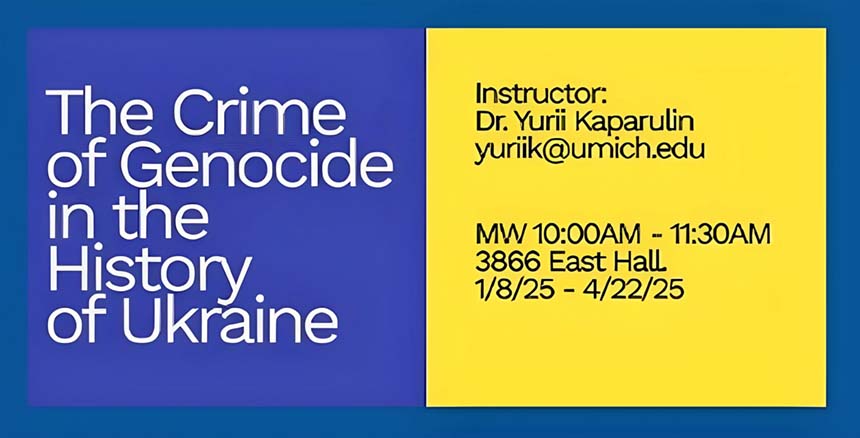

During a recent panel discussion organized by the Raoul Wallenberg Institute at the University of Michigan, my colleagues and I discussed the relevance of this topic and the applicability of the concept of genocide in different contexts. It was noted that the word genocide continues to carry an extremely high emotional charge and can evoke both sympathy and aggression. This may have contributed to my course, The Crime of Genocide in the History of Ukraine, being fully booked.

The curriculum specialists assigned my course to four major academic areas:

HISTORY 481 — European History Topics;

POLSCI 489 — Advanced Topics in Contemporary Political Science;

REEES 405 — Topics in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies;

SLAVIC 470 — Topics in the Cultural Studies of Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe.

In practice, this meant that the audience included students from various majors who had chosen the course as relevant for their academic program or as part of the humanities block among general disciplines. Recognizing this, I tried to make the course interdisciplinary from the beginning, focusing on the historical, legal, and political aspects.

Students had different motivations. Many wanted to learn more about Ukraine, largely due to the country's ongoing war against Russian aggression. Others were primarily interested in taking a three-credit course that met the Race and Ethnicity (R&E) requirements, which specified that each course had to cover such topics as the meaning of race, ethnicity, and racism; manifestations of racial and ethnic intolerance and inequality, particularly in the United States and other countries; and a comparison of discrimination based of race, ethnicity, religion, social class, or gender.

Some students had a Ukrainian background through older generations but pursued completely different majors. For example, one studied engineering and simultaneously underwent pilot training within a program that the University of Michigan implemented in cooperation with the US Air Force as part of the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC).

Course structure

The course had a chronological structure, covering the events of the 20th–21st centuries in three thematic modules:

- Introduction to the course. Genocide and mass violence during the Ukrainian Revolution and in interwar Soviet Ukraine (1917–1939)

- Genocide and mass crimes on the territory of Ukraine during World War II (1939–1945)

- Discussion of the genocidal experience in Ukraine in the second half of the 20th and early 21st centuries (1945–2025).

From the beginning of the semester, the course was taught in a peculiar political atmosphere as the US experienced the transition of power and performed sharp strategic maneuvers on Ukraine-related issues. A draft resolution "Recognizing Russia's actions in Ukraine as a genocide," introduced in the US Congress on 6 January 2025, states that the House of Representatives —

(1) condemns the Russian Federation for committing acts of genocide against the Ukrainian people;

(2) calls on the United States, in cooperation with North Atlantic Treaty Organization and European Union allies, to undertake measures to support the Ukrainian Government to prevent further acts of Russian genocide against the Ukrainian people; and

(3) supports tribunals and international criminal investigations to hold Russian political leaders and military personnel to account for a war of aggression, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

This certainly increased the course's relevance for the domestic audience, but the draft resolution was tabled after the Trump administration took over.

The first lecture covered basic information about modern Ukraine, its path to independence, and the key question: Why is the Ukrainian historical and contemporary context important? The next class looked at the definition of genocide in the context of the biography and professional activities of Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term, and his connection to Ukraine. We discussed the evolution of the concept in a historical context, its fixation in law after World War II, and its links to other international crimes.

The students watched the documentary Watchers of the Sky (2014) to understand the topic better. During the discussion, we reflected on how genocide became a global problem that spread to all continents over time. We also reviewed the map of genocides from Adam Jones' book and analyzed the Ten Stages of Genocide scheme from the Genocide Watch website, which proved to be especially useful during further study of historical cases.

Having mastered the basic knowledge of the crime of genocide, other international crimes, and manifestations of mass violence, we moved on to the analysis of these phenomena in the history of Ukraine. We began with the 1917–1921 Liberation Struggle, one of the most significant periods in national history. The Ukrainian territories were part of the Eastern Front of World War I. After the war ended, Ukrainian statehood was temporarily restored on the ruins of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, but establishing a lasting peace turned out to be impossible. Fighting and mass violence in various forms continued for several more years as numerous parties vied for both preserving the young Ukrainian state and controlling its territories.

We focused on the "white" and "red" terror, otamanshchyna (warlordism), decossacization, and the anti-Jewish pogroms that swept across Ukraine, committed by nearly all actors in wars and confrontations. We discussed individual chapters from a recent academic bestseller — a book by University of Michigan professor Jeffrey Veidlinger [1]. Special attention was paid to the description of the pogrom in Proskuriv (modern Khmelnytsky). Interestingly, one of the central participants in those events, General Anton Denikin, later died in a hospital in Ann Arbor, where the University of Michigan is located. This fact creates an unexpected link between distant history and modern local context.

The students reflected on the types of groups against which violence of various kinds was committed. On the one hand, this demonstrated how limited the definition of genocide is, as it covers only national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups. On the other hand, cases that do not fall under the current definition indicate that other crimes, which we today call war crimes or crimes against humanity, are no less significant. Crucially, there isn't — and should not be — a hierarchy of suffering in this system.

The students were given an opportunity to watch a short documentary about the exhumation of Red Terror victims in Kyiv and Kharkiv, which was recently found in a German archive and transferred to Ukraine. The mutilated bodies of Kyiv residents killed by the Red Army men make a no less shocking impression than do photographs of pogrom victims. These instances of mass violence may have had different motivations, but the consequences were similar.

Looking at interwar Soviet Ukraine, we focused on collectivization, the 1932–33 Holodomor, and the Great Terror. In particular, we analyzed dekulakization from the perspective of genocidal policies. Among the recommended materials, we discussed the ideas of Nicolas Werth, a French researcher of Soviet history, specifically his attempt to distinguish between "racial" and "class" genocides.

Two separate classes were devoted to the Holodomor. The first one introduced basic information using data from the HREC and MAPA projects. We discussed the genocidal nature of this crime. Rather than simply taking my view at face value, I wanted the students to independently come to an understanding of why the Holodomor should be studied as an example of genocide. This was especially important given that there are different points of view in the United States on the nature of this crime. A recent work by Kristina Hook was particularly helpful in this respect.

Those interested could also watch the feature films Mr. Jones (2019) and The Guide (2013), which helped understand the atmosphere of the time and added an American context to our discussion. As we engaged with collections of testimonies and memories of contemporaries during the second class, I shared parts of my family history with the students. The contribution of James Mace, a graduate of the University of Michigan, was also highlighted. This had a positive effect on bringing Ukrainian and American perspectives closer together, particularly the element of genocide against the indigenous peoples of America in this story.

In the final session, dedicated to the interwar period, we discussed the Great Terror in the USSR and Soviet Ukraine, focusing on genocide and political groups. We turned to the works of Robert Conquest, Anton Weiss-Wendt, and Norman Naimark. The new Ukrainian documentary project "Bykivnya, Babyn Yar, Bucha — between the massacre and its memory" provided us with a deeper understanding of the specific locations of the Great Terror and helped draw parallels with subsequent tragedies that occurred in the same places during World War II and the ongoing war in Ukraine. In this context, I shared with the students my reflections on the concept stratigraphy of violence [2] — a term I propose and use in my current research. The students could also watch the film Slovo House: Unfinished Novel (2023) about the elimination of Ukrainian writers under Stalin.

The next five-class module dealt with Ukraine's genocidal experience during World War II. We began with a review of the open aggression by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939 and the subsequent collapse of their alliance forged under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. A key activity was a discussion of the colonial perspective on the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 and the role of Ukraine in Nazi plans. Here, we greatly benefited from the well-known work of American researcher Wendy Lower.

The students researched US Holocaust Memorial Museum collections, trying to analyze, among other things, a documentary chronicle filmed by a German reporter who traveled to the occupied territories. (I assume that it was Leni Riefenstahl). We then discussed anti-Jewish violence and the Holocaust in Ukrainian lands, which claimed the lives of an estimated 1.5 million local Jews and those deported from the neighboring countries occupied by or allied with Nazi Germany.

To make the topic more accessible to the local student audience, we held an after-school session at the local memorial to Raoul Wallenberg, a University of Michigan graduate and Swedish diplomat who was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations for saving tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest. In 1944, he was arrested by Soviet intelligence agents. Wallenberg likely died in one of the Russian prisons, which also held many Ukrainian political prisoners, some of whom may have been his last companions in captivity.

We paid special attention to non-Jewish Nazi victims in Ukraine, who are also usually considered in the context of the Holocaust — Roma, POWs, people with disabilities, and communists. Students were offered a selection of documentaries for individual viewing and further discussion in the classroom, including Spell Your Name (2006), Wordless (2022), Shchedryk (2022), Kalinindorf (2020), Doomed: The History of the Rivne Ghetto (2019), (Un)Known Holocaust (2021), and others. However, my personal recommendation, as in previous years, was the Netflix documentary miniseries The Devil Next Door (2019), which I proposed to discuss additionally, having read the review by the Ukrainian Holocaust researcher Anna Medvedovska and American professor of Jewish studies Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern.

We looked closely at deportation as a tool for committing genocide during World War II, examining the cases of ethnic Germans (1941) and Crimean Tatars (1944) and analyzing related issues. The feature film Haytarma (2013) was chosen for viewing and discussion.

The last topic in the World War II module was the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation in Volyn. I formulated this question as "Volyn 1943: tragedy or genocide?" As you can see, this topic remains more politically charged than academically researched. Therefore, I had to be very careful in selecting the recommended texts and holding discussions with the audience. The texts included an interesting publication by Andriy Portnov on the "clash of victims." We also discussed why the Ukrainian formula "We forgive and ask for forgiveness" did not find sufficient support in Poland and what agreements and joint actions could contribute to overcoming trauma and achieving a coordinated common view of the past, particularly through exhumations at mass grave sites.

The third module was dedicated to Ukraine's genocidal experience after World War II. We returned to Raphael Lemkin and his essay "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine," which was relatively recently found in the New York Public Library archives. Thanks to the persistent work of Canadian researcher Roman Serbyn, this text was published and translated into 22 languages. What made Lemkin interested in the Ukrainian experience of genocide? The report does not provide a direct answer. Still, modern Ukrainian researchers have established that he collaborated with the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States, particularly Roman Smal-Stotsky and Lev Dobriansky. We then examined the life and research of the prominent researchers Robert Conquest and James Mace, who laid the foundation for further studies of Ukraine's genocidal experiences.

The next session revolved around the challenges of reinterpreting the traumatic past in independent Ukraine. We looked at the memorial legislation on genocides, which I tried to analyze in a recent publication.

Russia's war against Ukraine and the concept of genocide

We gradually came to discussing how the Russian Federation instrumentalized the concept of genocide in its aggression against Ukraine in 2014–2021. Relying on archival materials collected by international organizations, in particular Just Security, we traced how the rhetoric changed and hate speech intensified among Russian officials and institutions during these years and after the full-scale invasion.

Finally, we came to the topic of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which brought crimes on a scale not seen since World War II and utilized the history of that period in modern information warfare. Moreover, one of Russia's reasons for the full-scale aggression was the slogan of "preventing genocide in the Donbas," which makes this case unique in international practice because the Russian command and military did the exact opposite of what was declared.

Since 2022, the genocide committed by Russian troops and its characteristics have been mentioned in the speeches of many officials and remain on the agenda, along with setting up a special tribunal against the Russian Federation for its international crimes. Thus, one of our classes focused on the deportation and assimilation of Ukrainian children from the Russia-occupied territories of Ukraine. This falls squarely under one of the articles of the Genocide Convention, even though the current investigation by the International Criminal Court looks at this case in the context of crimes against humanity. During this binary session, we talked with Vladyslav Havrylov, a fellow with the Collaborative on Global Children's Issues at Georgetown University.

Considering the issue of intent as an integral element of the crime of genocide, we watched and discussed the documentary Destroy, in Whole or in Part, in which Ukrainian and foreign researchers and lawyers, such as William A. Schabas, Eugene Finkel, and Dmytro Koval, shared their assessments of the events.

Discussing the topic of collecting and preserving evidence about Russian crimes, its further use in the evidential base, international cooperation, as well as memory, memorialization, and education about the events of the current war, we turned to the outcomes of The Reckoning Project: Ukraine Testifies implemented with the Weiser Center for Europe and Eurasia at the University of Michigan as a partner.

The last topic of the course was transitional justice and Ukraine's prospects. We had the opportunity to listen and talk to the guest lecturer Olga Kotiuk, who teaches a course on transitional justice at the Kyiv School of Economics and specializes in armed conflicts and peacebuilding.

The last few sessions were set apart for student presentations, which highlighted additional topics and aspects that, due to a lack of time, could not be covered in detail in class. For example, the proposed topics included Russia's relativization of the experience of the Balkan wars and the Srebrenica genocide in order to justify its aggression against Ukraine, as well as instrumentalizing antisemitism in modern warfare.

The last class was about summing up the course, sharing impressions and wishes, and tasting Ukrainian chocolate. I invited the students to provide anonymous feedback, which is the final stage of the educational process, helping to improve the course content and teaching methods.

A key achievement of this course was that it formed empathy for the tragedies of other peoples and various groups. We highlighted the importance of preserving and protecting human rights and international law in general. This system is currently experiencing a deep crisis due to the actual inability of the world community to stop acts of aggression in a timely manner and bring high-ranking criminals to justice. In this context, I tried to present the Ukrainian case as unique, but not exceptional, in the modern world. This provided a space in which students could share their concerns. And this really matters. After all, my American colleagues often emphasize that education in the United States, from high school to universities, has a clearly expressed practical orientation. Elements of humanities education are frequently reduced to formal courses that students choose only to fulfill special credit requirements. As a result, this can affect the overall level of moral guidelines in society, which, in the absence of empathy, may develop indifference to injustice and an apathetic attitude towards protecting rights due to a sense of helplessness in the face of global crises. My experience teaching and interacting with students gives me hope that this can be resisted.

Students may have found it challenging to immediately immerse themselves in all the historical details discussed in the classroom. Therefore, the course material will need to be structured and summarized better in the next iteration, highlighting the most relevant issues for each topic. In fact, the students suggested, among other things, doing exactly that in the form of course handouts as a supplement to the syllabus.

To sum up, the University of Michigan remains a leading US academic center, offering a minor in Ukrainian studies. So far, it has mainly focused on studying the Ukrainian language and culture, but there is hope of expanding the thematic areas. Over the past three years, a number of additional courses have been taught at the university, including Theory of Hybrid Conflicts, Disinformation and Propaganda (in the context of the Russian-Ukrainian war), Architecture of Soviet Ukraine, and others — all offered by invited Ukrainian professors.

Forward, maize-and-blue wolverines of Ann Arbor!

The publication includes photos from open sources and Yurii Kaparulin's private archive.

References and notes

1 An interview with Jeffrey Veidlinger about his book In the Midst of Civilized Europe was published on the Ukraina Moderna website in 2022.

2 The stratigraphy of violence is an analytical concept that does not yet have a well-established definition. Acts of mass violence can be marked on the timeline in chronological order. At the same time, they are studied through the specific places where the crimes were committed. Traces of violence are sometimes preserved in the soil, imprinted in a vertical sequence of horizontal layers. For example, NKVD officers executed repressed individuals in the courtyard of the Kherson city prison during the Great Terror. Later, it was the site where the Nazis carried out the first mass murders of Jews during the Holocaust and executed other victims. In 2022, during the Russian occupation, this location became a symbol of a new wave of atrocities. Now, it is under constant shelling by the Russian army, which threatens the lives of civilians and leads to the destruction of material heritage, leaving local residents with scorched earth once again. This concept permits describing sequences of criminal acts and the accumulated traumatic experience of individuals and entire communities in a certain period and location, identifying causal relations between different violent acts, and analyzing their special characteristics and differences in a specific geographical and social landscape.

Yurii Kaparulin

Yurii Kaparulin

Associate Professor at the Department of National and International Law and Law Enforcement, Kherson State University, and Research Fellow at the Raoul Wallenberg Institute, University of Michigan. He received a PhD in History in 2012 and a Master's Degree in Law in 2022. His research interests include 20th-century Eastern European history, Holocaust and genocide studies, and human rights. Prof. Kaparulin has published in such academic journals as Holocaust and Modernity; The Ideology and Politics Journal; Colloquia Humanistica; City: History, Culture, Society; Holocaust Studies: A Ukrainian Focus; Eastern European Holocaust Studies, and Ukraina Moderna, as well as in popular media outlets (BBC News Ukraine). Currently, Prof. Kaparulin is working on his book Between Soviet Modernization and the Holocaust: Jewish Agrarian Settlements in Southern Ukraine (1924–48). He held postdoctoral positions at the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (2018–2019), Yahad-In Unum (2019), New Europe College (2021), and Zentrum für Holocaust-Studien (2022) and received the WCEE Scholars at Risk Fellowship (2022–2025). From 2020 to 2021, Prof. Kaparulin was the director and co-author of the documentary films Kalinindorf and (Un)Known Holocaust (2021 — ongoing).

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Ukraina Moderna

This article was published as part of a project supported by the Canadian non-profit charitable organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.