The Holocaust child and adult survivors’ memoirs

Today we are speaking with Anatoly Podolsky, the director of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, about the memoirs of two individuals who never knew each other, but who had very similar experiences. These are the memoirs of a little girl and of an adult male, both of whom survived the Holocaust.

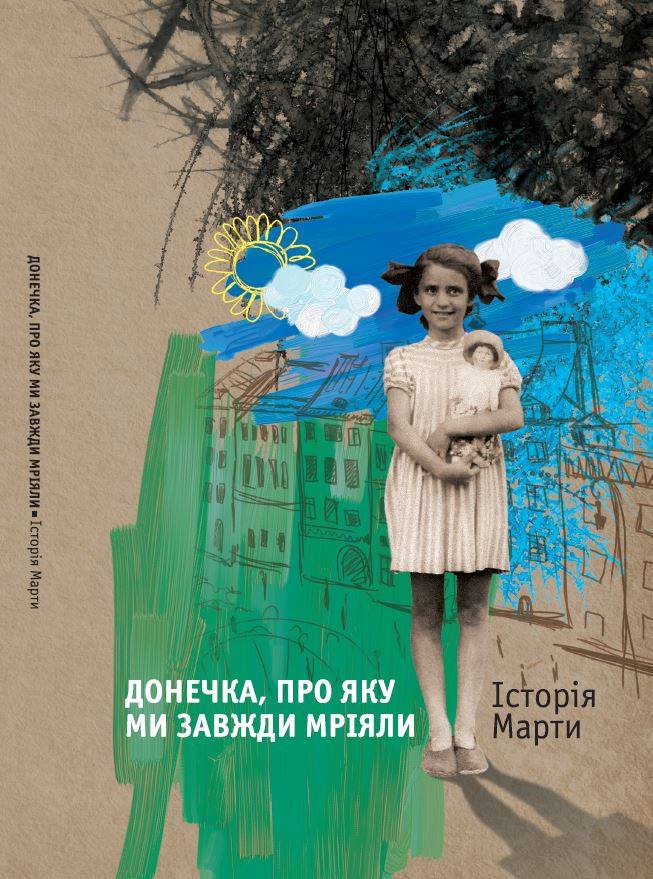

Andriy Kobalia: We are talking about two very different texts that were written by different people. I propose that we begin with the book, The Daughter We Had Always Wanted: The Story of Marta. Tell us who Marta was and about this text.

Anatoly Podolsky: Starting in 2012, the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies launched a series of books called “Library of Memoirs about the Holocaust.” This book is one of those supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. The main hero is Marta Goren, who is still alive today at the age of 85. I met her last year in Jerusalem. You can’t imagine the look in her eyes when she brought along her husband, children, and grandchildren—the entire family. This was during a methodological training seminar on the history of genocides and the Holocaust attended by a group of Ukrainian teachers. This is a project that for the last fifteen years has been training Ukrainian history teachers from all over the country. We presented Mrs. Goren with the Ukrainian edition. She could not believe that anyone in Ukraine needs this, that one day this text would be published in the Ukrainian language.

This book records the memoirs of Marta, who was born in Chortkiv. She was hidden from deportations by her Ukrainian and Polish neighbors. For her, this publication is a return to Ukraine. Book launches also took place in Chortkiv and Kyiv. Mrs. Goren’s memoirs are a unique example because they are not the memoirs of an adult; in 1942 she was almost eight years old. All these events—when you are being persecuted only because you were born Jewish—everything remained in her child’s consciousness. Thank God, she survived all this. How does one remain human in inhumane circumstances? We are fated to remember the brutality of the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. Various studies, documents, and materials equate the Bolshevik and Nazi regimes. We must always remember the typology and specific features. But this horror touched all Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews. And Mrs. Goren remembers this.

Andriy Kobalia: I have read a lot of memoirs by people who survived the Holocaust. As a rule, these memoirs are written by adults in their twenties, thirties, or older. Therefore, if we are talking about Ukraine, this is one of only a few examples of a large text that features a child’s reflections on the Holocaust. In your view, what makes this perspective special?

Anatoly Podolsky: Mrs. Goren was silent for many years. When we talk about the specific features of memoirs, testimonies, and memoiristic literature on this period, we must differentiate among them. For example, the diary of Dawid Rubinowicz, a Polish boy from Radom County, which we published as well; he wrote these memoirs during those events. Or the diary of Anne Frank and Roman Kravchenko, from Kremenets. These are the memoirs of teenagers, which they wrote immediately. It was different in the case of Marta Goren; she remained silent for a long time. She was located by Yad Vashem and asked to write her memoirs. It was on their initiative. Marta had not kept a diary; she didn’t write her memoirs after the war. She told her story, and our colleagues from Yаd Vashem recorded it. Our Center translates the memoirs of various people, both Jews and non-Jews, who lived through the Holocaust in the lands of Ukraine; our main criterion is the Ukrainian context. That is why we also translated Marta Goren’s memoirs. We obtained a copyright from Yad Vashem and translated this text from the English into Ukrainian.

When I spent time with Mrs. Goren in Jerusalem last year, she was surprised by the fact that Ukrainian teachers and students are interested in this topic. Such testimonies offer us something that neither the documents of the Nazi occupation or Soviet ones can: the human dimension—and in this case, that of a child’s. In speaking with Mrs. Goren, I realized that, even though she is an adult, these reminiscences are vivid, like those of a child who doesn’t understand how a person can behave this way toward another person.

Andriy Kobalia: Have I understood correctly that Marta survived the Holocaust, did not talk about those events for a long time, and was living at the time on the territory of the Soviet Union?

Anatoly Podolsky: No, thanks to her relatives, she emigrated. She obtained an education and a job as an Israeli. Her mentality was not Soviet at all. She was fluent in Polish and Yiddish. Her identity was Jewish, but for her, Chortkiv remained her small fatherland. Even today, at the age of 85, she speaks very warmly of Chortkiv. This is the specific feature of children’s reminiscences. We see a frank, naïve view: How can one behave this way? How can one take away the lives of people who did nothing wrong? Adults say that, unfortunately, the world is horrible and cruel, and it is always a challenge to remain a human being in inhumane conditions. Mrs. Goren has striking accounts of how she and her Polish and Ukrainian peers struggled for the life of animals. And this was when the life of a person was worth nothing when people were being killed, deported, and raped. In these conditions, children could show more sympathy than adults.

Andriy Kobalia: You mentioned Yad Vashem. I know that there is a tradition in Israel that when Righteous individuals, that is, people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust, are located, they are awarded the status of Righteous Among the Nations. Did any of those who rescued Marta Goren obtain this status?

Anatoly Podolsky: Yes, they and their families made contact in connection with this matter. Those who rescued her were awarded this status. For Marta, this was one of her life’s goals. Her book of memoirs appeared in the Ukrainian language thanks to the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies, the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, and Yad Vashem. For the last two years, it has been used for teaching events in our Center and in high schools. We have received feedback from teachers in Kharkiv, Odesa, and Lviv. In our bulletin Uroky Holokostu [Lessons of the Holocaust] we published an account of an assignment given by a Kharkiv-based teacher. First, the children read Marta’s memoirs. They’re quite simple; this is not a scholarly monograph or a text written by an adult. Then the teacher had the children write letters to Marta. She sent these letters to us, and we published them.

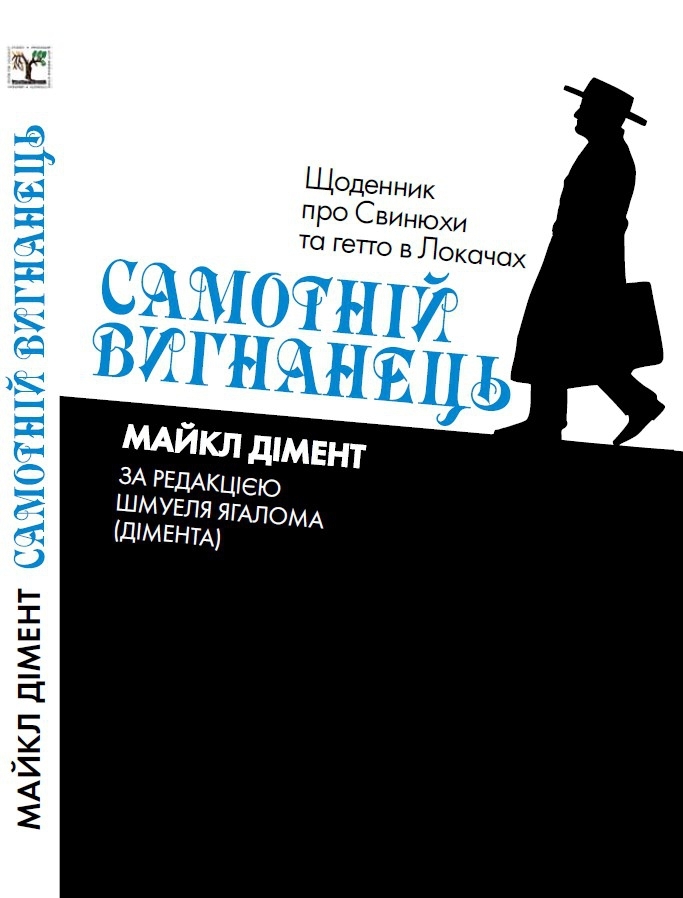

Andriy Kobalia: The second part of this conversation is devoted to other published memoirs: The Lone Survivor by Michael Diment, an adult who survived the Holocaust. Tell us what this book is about.

Anatoly Podolsky: We came across this book during the German-Ukrainian project called “Protecting Memory.” Within its framework, commemorative markers were installed at sites of mass burials of Jews in Ukraine. While working in the Volyn lands in the large village of Pryvitne (formerly Svyniukhy), Lokachyn raion, we found these memoirs, published in English. They have been used by European researchers; this book is entirely devoted to the Holocaust in Volyn. Unlike Chortkiv, Berezhany, or Ternopil, which were part of the occupation authority of the Generalgouvernement and from where people were being deported, those lands were under the General District of Volyn-Podillia of Reichskommissariat Ukraine, where shootings took place on the spot. This book moved my colleagues, and we decided to translate it. We published it in 2016 with the financial support of the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Andriy Kobalia: How did Diment, the author of these memoirs, survive? As far as I understand, these memoirs are written by one of the few people who survived the liquidation of a ghetto.

Anatoly Podolsky: That’s the point. These are all memoirs of people who survived. As an adult, he describes the ghetto, how he hid from the shootings. He wrote all this by himself, without dictating, in the 1950s–1960s, if I’m not mistaken. And the book came out in English in the West. The story of Diment and his family shows what occupation and a change of power can do to people. The people alongside whom he had lived and worked before the war, under Polish and Soviet rule, knew him well. Nevertheless, they went to the local police and were ready to kill him, betray him to the Germans. The horror of the situation lay in the fact that these behavioral strategies appeared as a result of the occupation. Diment writes in his memoirs that someone recalled that once he had spoken badly about [Symon] Petliura. Here we see the complex cross-section of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. In his text he poses a question that appears in many memoirs, for example, those of David Kahane, the rabbi of Lviv, who was saved by [Metropolitan] Andrei Sheptytsky, and who wrote Lvov Ghetto Diary. Why do I compare these two works? Both these authors ask: What happened to the people alongside whom I had lived? Why did they become antisemites? Why were they ready to take away civilians’ lives? The world is being destroyed before my very eyes; the author says. The people whom I had known before the war are becoming monsters. Such memoirs spur us to think about this even today, in the conditions of Russia’s aggression against our country. We must learn these lessons.

Andriy Kobalia: Have I understood correctly that in Diment’s memoirs people who did not suffer during the Holocaust but who also had to survive the conditions of the occupation are described mostly negatively? Were there examples of people who helped him?

Anatoly Podolsky: Oh, absolutely. He survived these events not least of all because along the way he encountered people who helped him. The people who recalled his bad words, they too fell prey to propaganda clichés because Petliura had never been in those lands, and they were not aware of the context of the Ukrainian National Republic. But there were other people, who remembered him as a nice neighbor, who shared their food with him, who hid him. That’s why Diment writes later that, despite everything, humaneness won out, because otherwise, I would not have survived. He does not make collective accusations; he does not say that all Ukrainians are like that. Responsibility is always individual. His questions are philosophical and conceptual, and they appear in many memoirs: Why do some people take such advantage of a change of power, and where does hatred come from? There is no doubt that influence was exerted by the Soviet period and Nazi propaganda, which proclaimed that “all Bolsheviks are Jews.” This is the stranglehold of collective responsibility. Just like Stalin said that “all Crimean Tatars are collaborators,” Hitler declared that “all Jews are communists.” All this had an impact on ordinary people. And despite everything, there were those among them who rescued [Jews].

Andriy Kobalia: To conclude our conversation, I have a question about Diment’s fate and where he spent his final years.

Anatoly Podolsky: He emigrated as well. Neither of these people stayed in Ukraine. They have feelings for these lands: Diment for Volyn, Marta for the Ternopil region. After all, they had lived here. But it was difficult for them to return because they had lost their loved ones in these lands. Diment ended up in the United States. He wrote his memoirs after the war. During the war he was 40 or older, I think. In other words, he was already a mature person. For us, it is important that these memoirs are, on the one hand, sources for researchers, and, on the other, that they are being used for educational purposes. They offer us what other documents do not.

This program is created with the support of the Canadian philanthropic fund Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.