The trident with Hebrew: What a Ukrainian-Jewish document from 1919 tells us

There are very few extant documents that illustrate the brief period of the coexistence between the fledgling Ukrainian state and independent Jewish communities in 1917–1920. Military actions, pogroms, and the displacement of millions of people were not conducive to preserving valuable papers.

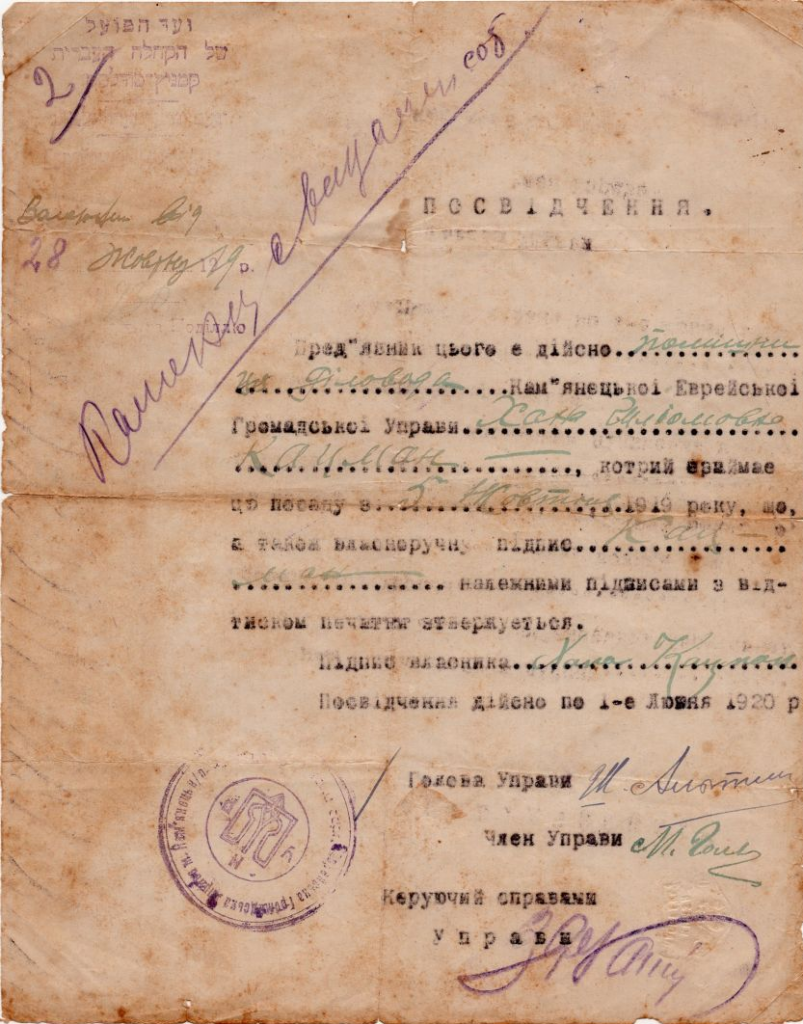

However, I was able to purchase one such document in June 2020 at an auction in Israel. It is a document attesting that one Khana Shliomovna Katsman is the assistant clerk of the Jewish Public Administration of the city of Kamianets-Podilsky.

I was not interested so much in Khana Katsman, who was an unknown historical figure, as in the design of the document dated 28 October 1919.

First of all, this Jewish community document is written in the Ukrainian language, which is entirely logical because, during that period, the city of Kamianets-Podilsky was not only the center of the Podilia Gubernia but also the temporary capital of the Ukrainian National Republic [UNR].

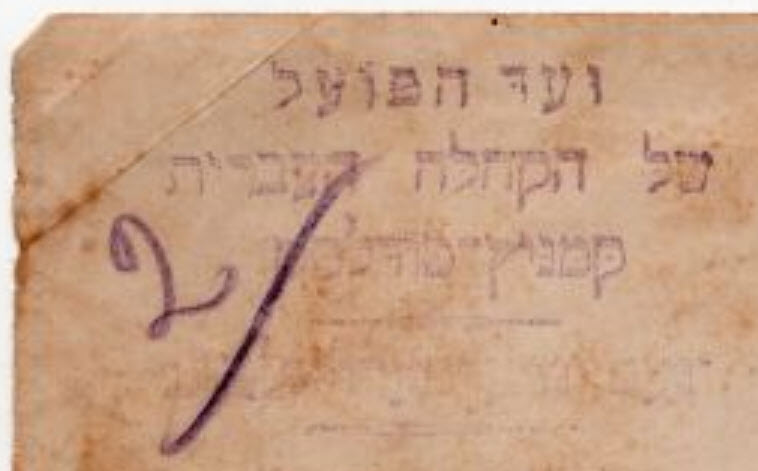

Second, in the center of the Jewish community's stamp is a trident with the inscription "UNR" and a Ukrainian/Hebrew parallel text.

Third, the Hebrew text, which appears next to the trident and in the left-hand corner of the document, indicates that at the time, this Jewish community was run by Zionists.

The Hebrew inscription is translated literally as: "Executive Committee of the Hebrew Community of Kamianets-Podilsky." The use of the word "Hebrew" instead of "Jewish" and the deliberate non-use of Yiddish was a distinctive feature of the Zionists, who supported the Jewish national revival in the Land of Israel.

In what context was this document created?

At the time, the city's Jewish population numbered approximately 23,000 people (47 percent of the total population). On 3 June 1919, the Third Division of the Army of the UNR took Kamianets-Podilsky by storm. On 6 June, the Directory and the government of the UNR moved from Kyiv and Vinnytsia to Kamianets, and for five months, the city was the capital of the Ukrainian National Republic.

Tuchbinder's Jewish Electrical Print Shop, the largest and most modern one in the city, became the main printer of brochures, proclamations, and orders issued by Symon Petliura's UNR government.

On 17 July, Petliura received a delegation from the Jewish community of Kamianets-Podilsky, demanding an end to the pogroms and the adoption of decisive anti-pogrom measures. The Jewish representatives declared that Jews were ready to support the government of the Directory only if the pogroms ceased completely.

Riding on a wave of successful Ukrainian battles, a meeting of the leaders of the UNR, the ZUNR [Western Ukrainian National Republic], and delegations of Western allies from Great Britain, France, and the U.S. took place in the city on 30 July 1919. Supreme Otaman Symon Petliura requested military and technical assistance from the Entente countries in order to arm the Ukrainian army and topple the Bolsheviks in Ukraine.

Apparently, the "capital city" status of Kamianets-Podilsky and the UNR government's desire to look good in the eyes of the Western allies helped maintain order in the city.

Did anti-Jewish violence take place in this city? There are two opposing points of view. The Shorter Jewish Encyclopedia (Israel), relying on a book about pogroms in Ukraine written by Ilya (Elias) Tcherikower (1881–1943), states that the three-day-long battles for the city in June 1919 were accompanied by pogroms, during which 52 Jews were killed in Kamianets and 78 Jews in the suburb of Kytaihorod. "As a result of the pogroms in Kamianets-Podilsky, a total of around 200 Jews were killed in 1919, and in 1921, 16 Jews were shot by Red Army soldiers," the Encyclopedia states.

Tcherikower is categorically challenged by Oleksander Udovychenko, General-Ensign of the Army of the UNR and future vice-president of the UNR in exile. Udovychenko commanded the Ukrainian forces during the capture of the city. In his memoirs, which are not devoid of anti-Jewish stereotypes, he thus describes the army's meetings with delegations of city residents on 3–4 June 1919:

"I addressed the representatives of the Jewish residents of Kamianets separately. The content of my address to them was as follows:

The Jewish inhabitants are citizens of the UN Republic, but they offered the greatest resistance to the national aspirations of the Ukrainian people. The events in Kamianets-Podilsky are a vivid and annoying illustration of this conduct of theirs. The Ukrainian authorities will not permit lawlessness and pogroms, but on my part, I request that shuttered shops be opened immediately and that you help us obtain FOR CASH everything that a soldier most lacks: underwear, footwear, clothing, soap, tobacco, etc. In your secret underground vaults, there are enough of these goods for an entire army. That is all I ask of you.

In response, the Jewish rabbi promised that all this would be done, and he noted that the Jewish population believes that the Ukrainian authorities would maintain order in the city: 'As for our young people,' the rabbi added, 'we cannot be responsible for them because they do not listen to us.'

This conversation, which was conducted in public, had a calming effect on the Cossacks. After the rabbi concluded his brief public speech, he turned to me and said, whispering: 'The Jews can voluntarily raise funds in the form of a contribution in the amount of 5 million karbovantsi, as long as there is peace in the city.' Of course, this Jewish 'tactic' outraged us, and the proposal of a 'voluntary contribution' was rejected on the spot.

From the foregoing, it is evident that we used all possible measures so that the Jewish population would not suffer as a result of revenge for their transgressions against the Ukrainians. On 4 June, there were no anti-Jewish public riots, and therefore all Jewish shops were opened. All this did not prevent the Jewish journalist Chirykovir [Tcherikower] to accuse me and my command staff of a pogrom in Kamianets-Podilsky. During the entire existence of Ukrainian power, there was not a single pogrom in Kamianets."

One can hardly talk about the ideal character of Ukrainian-Jewish relations in this city. In his book, Tcherikower recounts the story of a young Jew with the surname Khomsky, who participated in Jewish self-defense efforts in Kamianets-Podilsky.

In the summer of 1919, Khomsky was arrested, and a show trial was held. The young man was charged with taking part in a battle against part of the regular Ukrainian army and was sentenced to death as a Bolshevik and a leader of the struggle against the Ukrainian army. Khomsky spent four months in prison, hovering between life and death. Incidentally, it was in this prison that Khomsky met Otaman Semesenko, who had organized a bloody Jewish pogrom in February 1919 in Proskuriv (today: Khmelnytsky). After being sentenced, Semesenko was not shot; on the contrary, he was released from jail.

Perhaps additional archival documents are needed in order to figure out whose version about anti-Jewish violence in the city is closer to the truth: Tcherikower's or Udovychenko's.

Nonetheless, one fact is known: In late October 1919, when that document was drawn up for Khana Katsman, the Army of the UNR and the ZUNR was experiencing military defeats and was exhausted by a typhus epidemic. Before long, the Polish army entered the city, and then the Polish-Soviet war began in 1920, which led to further bloodshed.

In Israel, I did not succeed in locating any references to Khana Katsman. Perhaps she was an ordinary young Zionist, who, after a day of working in a lowly position at the Jewish community of Kamianets, managed to come [to Israel] in the 1920s and take part in building the future Israel. The young woman did not leave behind any noticeable trace in history, and in our time, her grandchildren or great-grandchildren put up at auction this "unnecessary" document.

If a museum devoted to the history of Jews in Ukraine is ever established in Kyiv, I will gladly donate to its collection this document that records the partnership between the Ukrainian and Hebrew languages and between the independent Ukrainian republic and the Jewish national movement in the dramatic months of 1919.

Text and photos: Shimon Briman (Israel).

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.