"The Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter: Cultural Dimensions": Part 1.1

The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter was founded in 2008 with the goal of building stronger relations between Ukrainians and Jews, two peoples who, for centuries, lived side by side on the territory of what is modern-day Ukraine. Since then, in keeping with its motto, "Our stories are incomplete without each other," UJE has sponsored conferences, round-table discussions and research, as well as translations and publication of works the organization anticipates will promote a deeper understanding between the two peoples and an appreciation of their respective cultures.

We offer for the first time the book The Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter: Cultural Dimensions in an eBook format.

The book is a collection of essays that examine the interaction between the Ukrainian and Jewish cultures from the seventeenth century onwards. Written by leading experts from Ukraine, Israel, and other countries, the book presents a broad perspective on parallels and cross-cultural influences in various domains — including the visual arts, folklore, music, literature, and language. Several essays also focus on mutual representation — for example, perceptions of the "Other" as expressed in literary works or art history.

The richly illustrated volume contains a wealth of new information on these little-explored topics. The book appears as volume 25 in the series Jews and Slavs, published by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem since 1993. In several previous volumes, considerable attention is given to the defining role of the Old Testament in Ukrainian literature and art and to the depiction of Jewish life in Ukraine in the works of Nikolai Gogol, Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko, Lesia Ukrainka, Vladimir Korolenko, and other writers.

This collection of essays was co-edited by Wolf Moskovich, Professor Emeritus, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Alti Rodal, Co-Director of the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, who also wrote the introduction to the volume. It was published in 2016 by Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.

Part 1.1

Allegories of Divine Providence in Christian and Jewish Art in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Ukrainian Lands

Ilia Rodov (Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan)

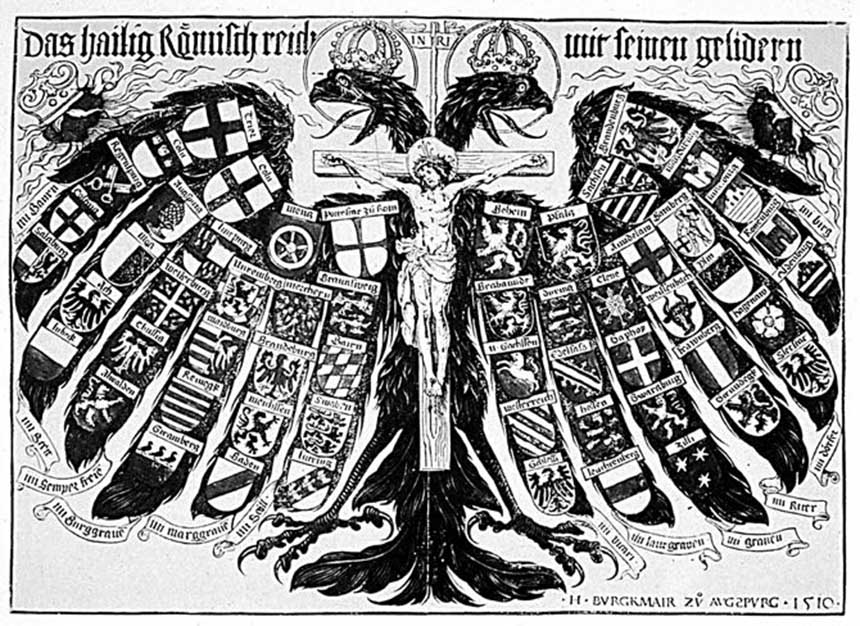

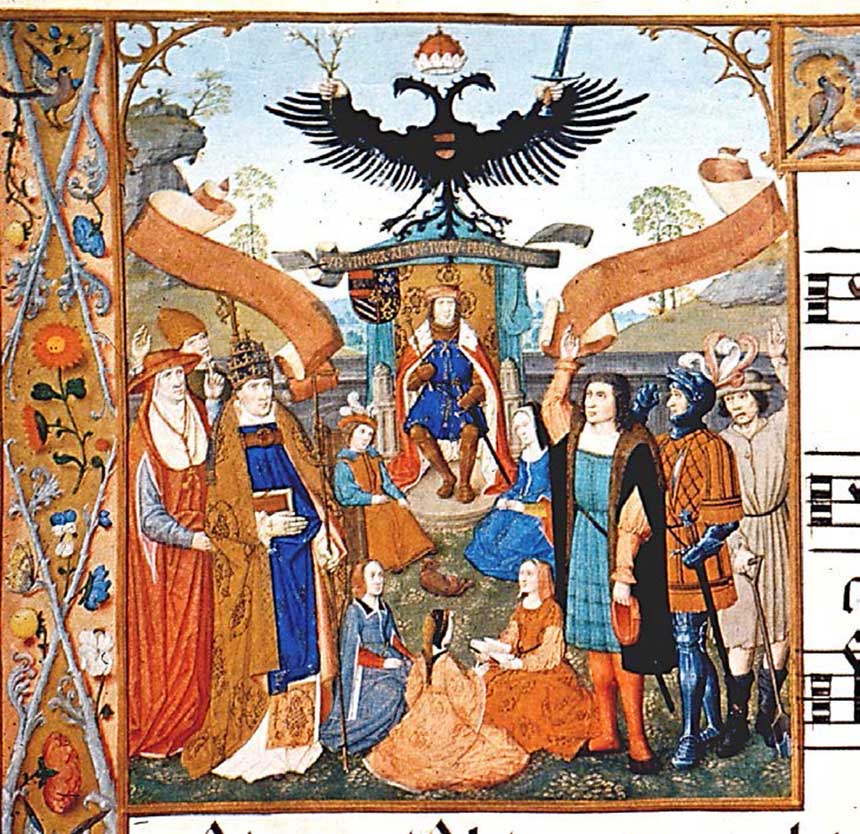

The issue of divine providence and protection became topical during the mid-seventeenth century in the Ukrainian lands. The Orthodox Ruthenians living in the epicentre of the encounter between the Catholic, Christian Orthodox, Protestant, and Muslim powers, sought religious and political allies. The struggle of the Ukrainian Cossacks against the Catholics entailed aggression towards their Jewish neighbours as well. When contemplating divine intervention in their destiny, the Ukrainians and Jews similarly transmitted their ideas through a visual model that represented — symbolically or figuratively — the celestial patron as if physically protecting the people under his or her outstretched limbs. The iconography was not newly invented, but adopted from the art of the two empires flanking the Ukrainian lands: the Holy Roman Empire of the Habsburgs and the Muscovite Tsardom. Jews and Christians derived metaphors relating to divine protection from the same biblical sources: Exodus 19:4, which recounts God's protection over the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, "I bare you on eagles' wings, and brought you unto myself," and Deuteronomy 32:11, which allegorizes God's providence as an image of the eagle who "stirs up her nest, flutters over her young, spreads abroad her wings, takes them, bears them on her wings." Yet, in a departure from the biblical discourse, both Christian and Jewish artists rendered the symbolic eagle as double-headed. Occasionally, Ukrainian artists also applied the symbolic protective wings to other divine figures. A comparison of the genesis and message of that imagery is the subject of this paper [1].

To the north of the Ukrainian lands, the double-headed eagle was the emblem of Muscovy. The Byzantine heraldry had been borrowed directly in the late fifteenth century by Ivan III in reaction to the Habsburgs' earlier use of it as their imperial symbol. [6] After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Ivan III had married Zoe (Sophia) Paleologue, a niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, and claimed his kingdom to be the successor of the Eastern Roman Empire. [7] The great state seal of Ivan III's grandson, Ivan the Terrible (1530–84), who asserted that he was an offspring of August the Emperor, employs the eagle as the symbol of an empire blessed by Christ that unites its members under its wings (fig. 4). [8] The sacredness of the kingdom is denoted by the "Golgotha Cross" above the eagle; one more cross on the eagle's crown; and Saint George, the holy patron of Moscow, on the eagle's breast. The other medallions in the proximity of the eagle designate the Russian lands. Thus in the sixteenth century, both the Russian double-headed eagle and the Habsburg's Quaternionenadler were not mere heraldic emblems but also a sign of God's protection over the state.

Another Christian image that denotes divine protection over individuals and society as a whole is the veil of Mary, whose names in Greek, Σκέπη, and in Russian, Покров, have similar meanings of a "veil" or "cloak" as well as "protection." An early-sixteenth-century icon from Moscow (fig. 5) exemplifies the Slavonic iconography of Mary's protective veil. [9] The painting illustrates the legend of a tenth-century miracle that happened to a certain Andrew who witnessed the descent of the Virgin together with a host of saints in the Blachernae church in Constantinople. The painting shows Andrew in the bottom centre, in front of the Royal Gate of the iconostasis in the church. The Virgin had interceded with Christ on behalf of all Christians and then spread her veil over the congregation in the church as a protection. [10] The figures of a tsar, depicted in the chair to the left of Andrew, and a metropolitan to the right of him, imply that Mary blesses and protects both secular and sacral rulers. Two centuries later, a Ukrainian painter of the Intercession icon (fig. 6) adapted the story from Constantinople to his reality [11] by locating Mary with her veil in the church of Sulymivka near Kyiv, dressing the dignitaries in the fashion of his time and inserting Ukrainian Cossacks into the congregation.

In the Western version of this iconography, Mary shelters the people under her outspread cloak. The Latin term for these images, Mater Misericordiae, accents the aspect of divine mercy, and their German name, Schutzmantel-madonna, stresses Mary's role of protectress. The Mater Misericordiae model also had an impact on the icon painters in the Ukrainian lands since the seventeenth century. Like the Intercession from Sulymivka, an eighteenth-century Ukrainian Mater Misericordiae icon communicated a political message by including the Christian Orthodox Archimandrite on the left of Mary and the Russian Tsar with the Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky on her right (fig. 7). [12]

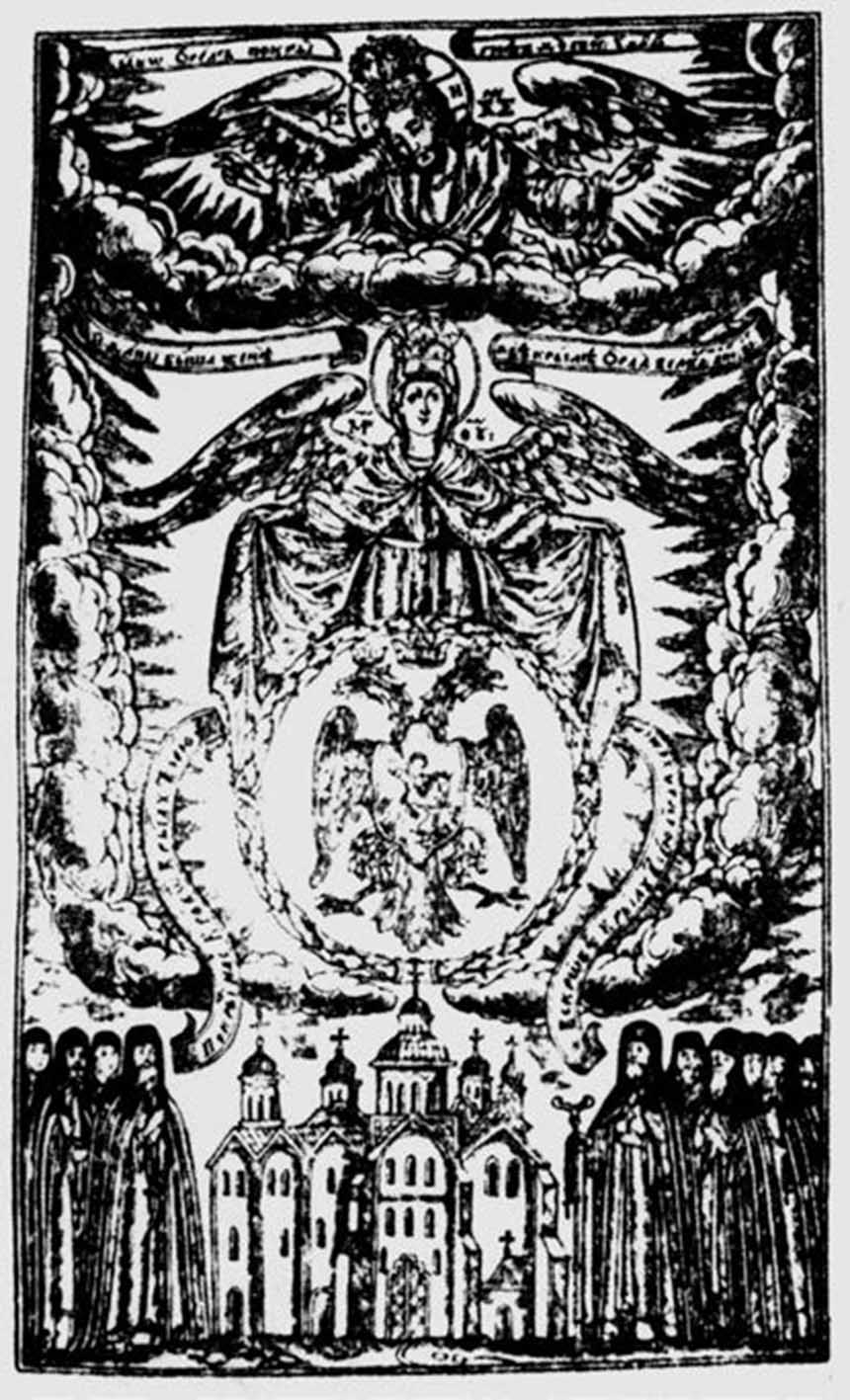

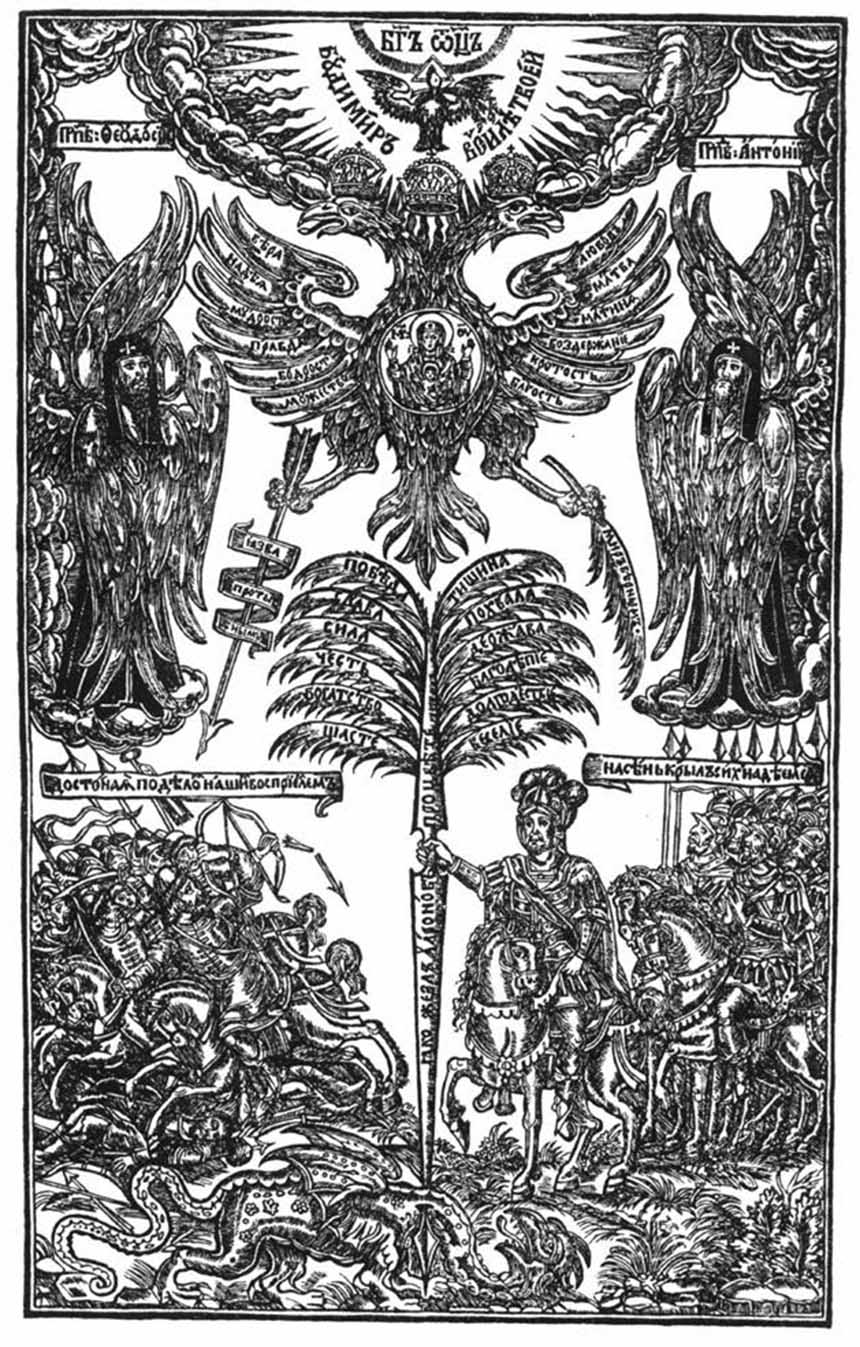

The symbolism of the double-headed eagle and Mary's veil of mercy became pivotal in the propaganda for the political and religious alliance of Khmelnytsky's Cossack Hetmanate and the Tsardom of Russia that was established in 1654. The delegation sent by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich to Kyiv in order to accept the Cossacks under the Russian crown presented to Khmelnytsky a standard portraying the holy protectors of the Orthodox Ruthenians: Christ, Mary stretching her veil to protect the faithful, and saints, including sanctified monks of the Orthodox Pecherska Lavra (Monastery of the Caves) in Kyiv. [13] As a response, Khmelnytsky saluted Aleksei Mikhailovich as "an eagle that stirs up her nest," quoting Deuteronomy 32:11, in order to emphasize that the Tsar "stretched his royal mercy over Kyiv and all Lesser Russia [i.e., Ukraine]." [14] A member of Khmelnytsky's delegation to Moscow, Ukrainian Archimandrite Innocent Gisel [Innokentii Gizel] (ca. 1600–83), [15] reasserted this rhetoric on the frontispiece of the Paterik Pechersky, a hagiography of the Lavra's monks published in Kyiv in 1661 (fig. 8). [16] The same biblical quotation, "as an eagle stirs up her nest" is written here on two banderoles above Christ, thus associating him with the divine eagle. In this depiction, Christ delegates his protection Fig. 8. Paterik Pechersky (Kyiv, 1661), frontispiece. to Mary, who grants her mercy to the Russian eagle hovering above the Uspensky (Dormition) Cathedral and the patriarchs of Kyiv's Pecherska Lavra. In contrast to the mere semblance of the crucified Christ's arms and eagle's wings observable in the symbolic images of Habsburg's imperial eagle, the artist of the Paterik frontispiece gives a pair of actual eagle's wings to both Christ and Mary, explaining the portrayal of a winged Mary with the apocalyptic verse "and to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle" (Rev. 12:14), which appears in the banderoles above her figure.

Both the German-born Gisel and the engraver of the Paterik illustrations, the Lavra's monk Illya, were Orthodox clerics well acquainted with Western art, [17] and their frontispiece wood engraving merged the eastern and western iconographic traditions. Mary's descent from Christ to a church and its congregation repeats the layout of the Russian icons of her intercession (cf. fig. 5), whereas the veil shown as a cloak with outstretched edges rather than as a shawl above her head replicates the Catholic iconography of Mater Misericordiae. The Russian eagle under its celestial protectors is an antithesis to the Catholic pictures, where the divine eagle is Habsburg (fig. 1) and the location of the Russian state emblem above a church in Kyiv symbolizes the political and religious protection of Muscovy over Ukraine.

Gisel's utilization of western sources is even more apparent in the frontispiece of his own book, Mir z Bogom chelovieku (Peace with God for Man) (fig. 9), compiled after the annexation of eastern Ukraine to Russia in 1667 and printed in the Lavra in 1669. [18] Here, the Russian eagle with its raised pinions is modeled on the Habsburg emblem (e.g., figs. 1–3) rather than on the Byzantine-styled eagle with its wings turned down as that depicted in the Paterik. The eagle is now the dominant image, and — like in the Habsburg art (cf. fig. 3) — the agent of the dual aspects of divine providence that cares for the faithful and punishes the infidels. The eagle stretches its right claw with a palm branch inscribed with "Peace to the Faithful" over the Russian Tsar and his army who, as this reads in the banderole above their heads, "trust in the shadow of these wings." The arrow inscribed "Sore for the Enemies" in the eagle's left claw threatens the Poles who, as one learns from the scroll, "get their deserts." [19]

Jewish chronicles and folk legends epitomized the Khmelnytsky uprising of 1648–49 as a national disaster comparable to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem followed by the exile. [20] As with the traditional interpretations of the destruction of the Temple, the massacres of Jews during those years were accepted as God's retribution for those who abandoned the Torah. [21] The survivors believed that divine anger would be tempered with divine mercy [22] that would ultimately bring messianic redemption to God's chosen people. The concept of the sheltering of the righteous "under the wings of divine presence," which echoed biblical discourse regarding the eagle bearing the exiles on its wings to God (Ex. 19:4), became a common idiom in Jewish chronicles of the Khmelnytsky persecutions. In the eulogy compiled in memory of the victims, Yom Tov Lipmann Heller (1579–1654) begged: "God, full of mercy, give right repose to the souls of the murdered under the wings of divine presence, […] for the merits of the martyrs gather the dispersed." [23] The synagogue painters utilized the double-headed eagle as the image best able to signify God's rule over the world, the duality of justice and mercy within divine providence, and hope for redemption under the wings of God's presence.

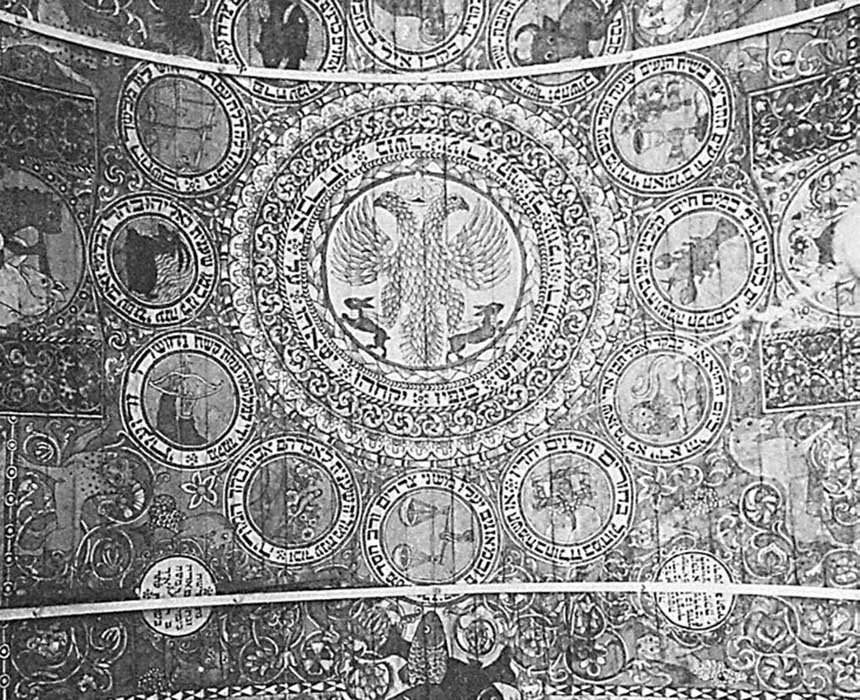

In the centre of the ceiling painting, tentatively dated 1714 (fig. 11), [24] in the synagogue in Khodoriv (Polish: Chodorów) near Lviv, the verse from Deuteronomy 32:11 written around the double-headed eagle identifies it as a symbol of divine protection over individual men, who are represented by small hares whose necks are grasped in the eagle's claws. [25] The verse about the eagle fluttering around its young and taking them heavenwards suggests that the painting represents the eagle rescuing the hares rather than cruelly preying upon them. [26] This aspect is clearer in the ceiling painting of ca. 1746 in the synagogue of Smotrych (fig. 12), where the eagle embraces the hares' waists and looks into their eyes. The small stars between puffy patterns on each side of the eagle represent the sky. In the Khodoriv synagogue, the eagle within the sun-like circle surrounded by the signs of the Zodiac suggests God's eternal government over the universe. The unity of the double-headed eagle is emphasized by the single great crown above both its heads.

The eagle's double heads may imply God's rule over both sides of the world, but also may connote the duality of divine justice and mercy that was a dominant topic in the Jewish chronicles of the Khmelnytsky period, as well as a prevalent motif in the frontispiece of Gisel's book. The worldviews of the Jews and Ukrainians were modeled on a common topos: providence pursues the sinners but has mercy on the righteous who find shelter under Divine wings. The difference is in the identification of the sides. For Gisel and his engraver, the eagle protects Orthodox Muscovites and pursues the Polish Catholic enemies (cf. fig. 9). The Jews believed that they, the "eagle's young," are subjects of both divine anger and paternal protection. Unlike the groups of people shown as objects of divine protection in Ukrainian art, the hare allegory in Jewish art conveys the idea of God's care of each individual person. In contrast to the Christian hierarchic schemes of divine providence that sanctify the present social order, the Jewish images are concerned with the ideal order of the world.

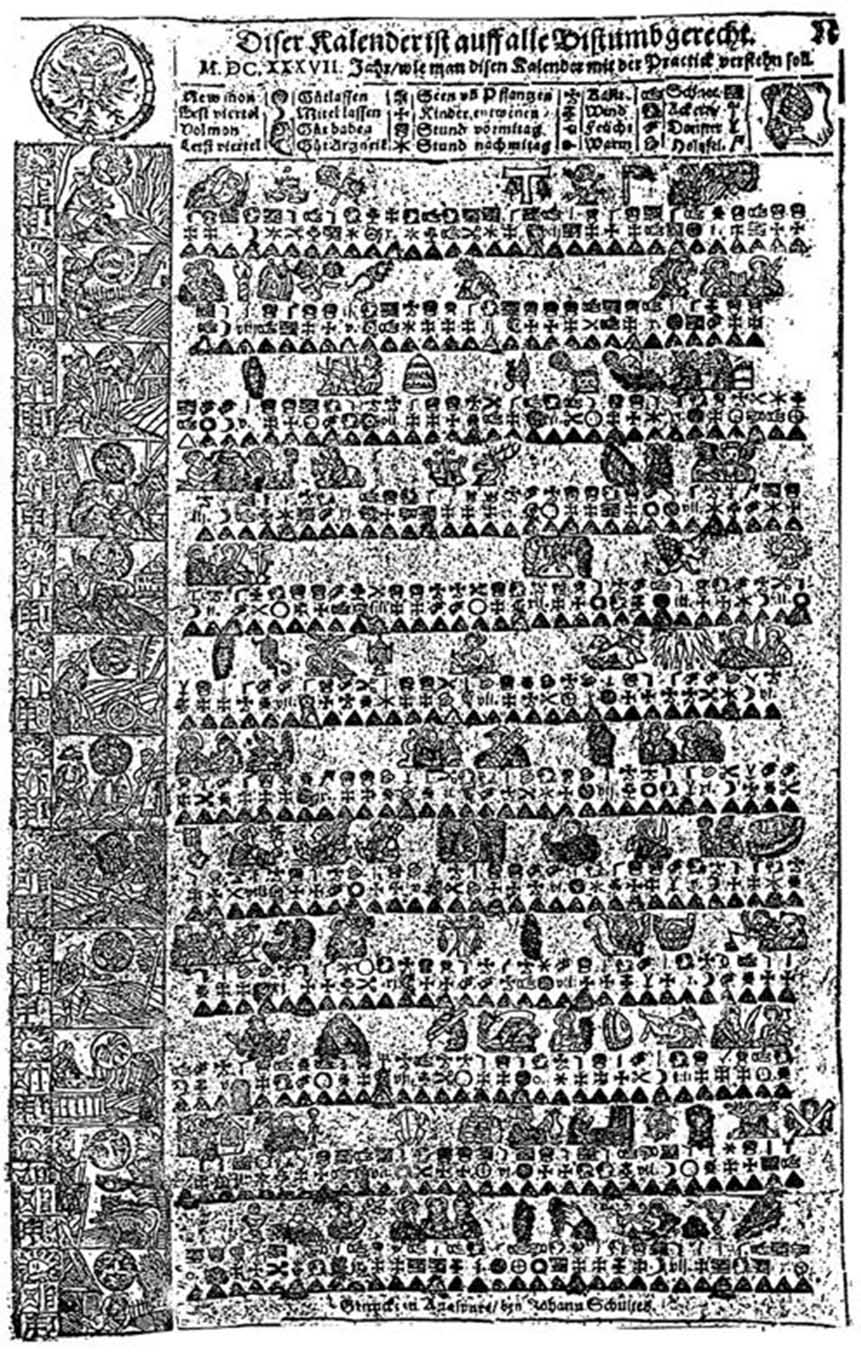

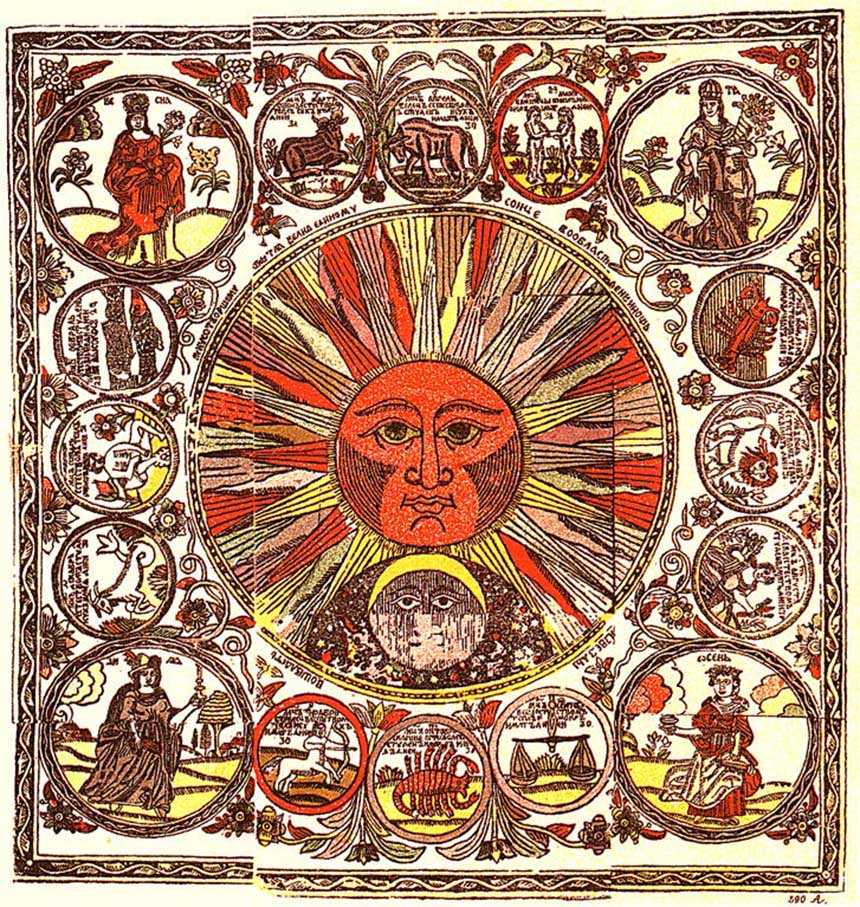

To the best of our knowledge, no church contained a painting of the double-headed eagle within the wheel of the Zodiac such as that found in the Khodoriv synagogue, but similar motifs circulated in prints. Here, as elsewhere in Europe, the book illustrations and single printed sheets facilitated the migration of images across cultures and served as a model for wall paintings. The eagle within the circle above the twelve pictures of labourers and the Zodiac sings as if ensuring the proper sequence of times in Johann Schultes's Catholic printed calendar for the year 1637 (fig. 13). The sun surrounded by the signs of the Zodiac was painted on the ceiling of a wooden palace of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich in Kolomenskoye near Moscow in 1667–69, and copies of it in folk prints have been found as far as Ukraine (fig. 14). [27]

The image of the double-headed eagle was disseminated via Christian prints and paintings and also became part of church design. The eagle is seen above the carved wooden Royal Gate in the Mary's Intercession icon (fig. 6) that is thought to be a depiction of the lost iconostasis from the Sulymivka church. An iconostasis crowned by a carved wooden eagle (fig. 15) is still to be found in the Spaso-Preobrazhens'ka (Transfiguration of the Saviour) Church of 1734 in Velyki Sorochyntsi. As in the Russian political graphics and the Intercession icon of Sulymivka, the eagle designates divine providence that is transmitted through the spiritual protection of Orthodox Russia.

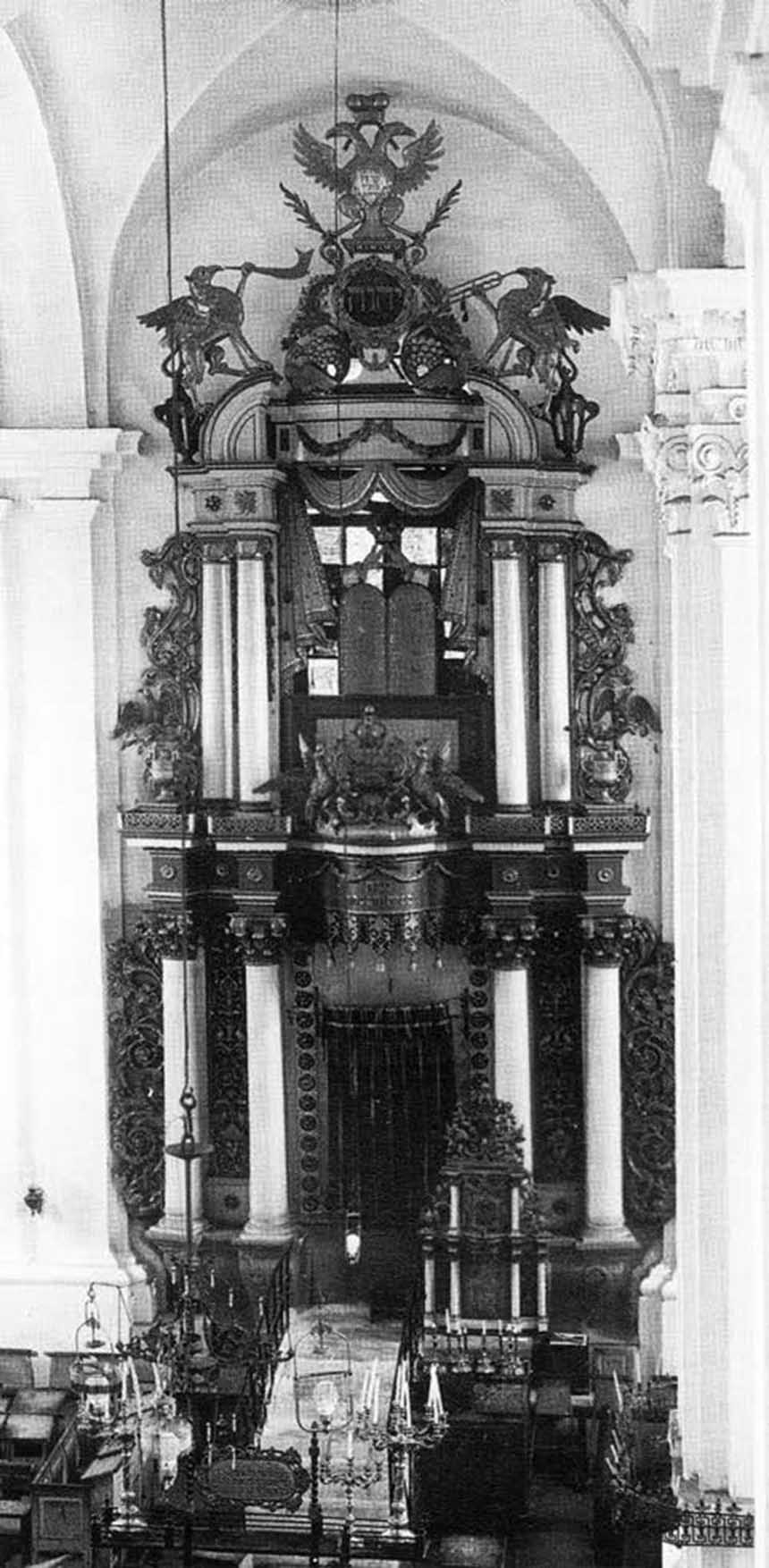

A similar transition of this image into sculptural decoration occurred in Eastern European synagogues, where a sculpted double-headed eagle symbolizing God's rulership and providence was often set atop the Torah ark (fig. 16), the bimah, and other ritual objects.

Muscovy, the late 17th or the early 18th century.

The politically charged symbol of the double-headed eagle encouraged the Ukrainians during their struggle for dominance of the Orthodox Church in their lands. After that aim had been achieved when Ukraine was more fully integrated into the Russian Empire in the late eighteenth century, this symbol disappeared from their ecclesiastic art. The aviamorphic symbol of divine providence in synagogue art sublimated the traumatic Jewish experience of the Khmelnytsky massacres. Even after these historical and psychological connotations had faded, the double-headed eagle continued to be a prevalent symbol of the divine in wood engraving. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek. Jewish art in Ukraine and surrounding lands — Lithuania, Belarus, Poland, and Romania — until the Holocaust.

[1] This research, based on my lecture at the conference "Ukrainian Jewish Encounter: Cultural Interaction, Representation and Memory" organised by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter Initiative (Canada) in collaboration with the Israel Museum and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem (Jerusalem, October 18–20, 2010), became a part of the project supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 326/13) and was published in Judaica Ukrainica, 3 (2014): 105–127.

[2] Zapheiriou, N. The Greek Flag from Antiquity to Present (Athens, 1947), 21–22; Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, ed. Alexander Kazhdan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 472, 669.

[3] I discussed the double-headed eagle motif in Habsburg art more extensively in my "The Eagle, Its Twin Heads and Many Faces: Synagogue Chandeliers Surmounted by Double-headed Eagles," Jewish Ceremonial Objects in Transcultural Context (Studia Rosenthaliana, 37, 2004): 77–129.

[4] "Nam quod extendit in patibulo manus, utique alas suas in Orientem Occidentem que porrexit, sub quas uniuersae nationes ab utraque mundi parte ad requiem conuenirent," Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius, "Epitome divinarum instituionum," Patrologia Latina, ed. Jacques-Paul Migne (Paris, 1844), 6:1058, chapter 51.

[5] The sword and the white lilies are standard symbols of Christ's judgment and mercy, respectively, in the images of the Last Judgment in Early Netherland paintings. For example, see Hans Memling's Last Judgment, oil on wood, 1466–73, Gdańsk, Muzeum Narodowe.

[6] See: Alef, Gustave. "The Adoption of the Muscovite Two-Headed Eagle: A Discordant View," Speculum 41, no. 1 (1966): 1–21.

[7] Poe, Marshall. "Moscow, the Third Rome: The Origins and Transformations of a 'Pivotal Moment'," Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas (2001): 412–29.

[8] Lakier, Aleksandr B. Russkaia geraldika (Moscow, 1990), 141–45.

[9] Alpatov, M. V. Early Russian Icon Painting (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1978), 29, 31, 318 167–68.

[10] Wortley, John. Studies on the Cult of Relics in Byzantium up to 1204 (Aldershot: Ashgate Varorium, 2009), 149–54.

[11] Shedevry ukrains'koho ikonopysu ХІІ-ХІХ st. (Kyiv: Mystetsvo, 1999), 114–15.

[12] Essential research on the Polish and Ukrainian iconography of Mater Misericordiae is found in Mieczysław Gębarowicz’s Mater Misericordiae-Pokrow-Pokrowa w sztuce i legendzie środkowo-wschodniej Europy (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1986).

[13] The standard is known to us only from its description in Bantysh-Kamensky, D. Istoriia Maloi Rossii (St. Petersburg, 1903), 528.

[14] Akty, otnosiashchiesia k istorii Yuzhnoi i Zapadnoi Rossii, 10 (St. Petersburg, 1878) no. 4, 216–17.

[15] Sumtsov, N. F. "Innokentii Gizel," Kievskaia starina, 10 (1884), pp. 183–226; Encyclopedia of Ukraine (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), 2:58.

[16] A manuscript translation of the Polish Paterykon abo żywoty ss. Oycow pieczarskich (Kyiv, 1635) into the Church Slavonic was completed by the Archimandrite Joseph Trisna in 1656. Gisel added an introduction praising the Russian Tsar to the book and inspired the symbolic design of the frontispiece. Forty-eight woodcuts for this edition were produced by Illya, a Lavra monk, in 1655–60. See: Yakym P. Zapasko and Yaroslav. Isaevych, D. Pamiatky knyzhkovoho mystetstva. Kataloh starodrukiv, vydanykh na Ukraini, 1 (1574-1700) (Lviv: Vyshcha shkola, 1981), no. 402.

[17] Gisel was born to a German reformist family in East Prussia, left for Volhynia where he converted to Orthodoxy, and then studied theology, including Catholic writings, history, jurisprudence, philosophy, and languages at the Kyiv College and at European universities. See: Sumtsov, N. F. "Innokentii Gizel," Kievskaia starina, 10 (1884), 183–226; idem, K istorii yuzhno-russkoi literatury, no. 3 (Kharkiv, 1885), p. 3. Ilya widely copied Dutch and German prints. See: Rovinskii, D. A. Russkie narodnye kartinki (St. Petersburg, 2002; reprint of St. Petersburg: R. Golike, 1900), 21–22, 39.

[18] Zapasko and Isaevych, Pamiatky knyzhkovoho mystetstva, no. 458; A. A. Guseva, T. Kameneva, N. and Polonskaia, I. M. Ukrainskie knigi kirillovskoi pechati ХVI–ХVII vv. 2 (Moscow, 1981), 1, p. 115.

[19] Numerous versions of the iconographic scheme of Gisel's allegories were popular in the Ukrainian and western Russian lands until the first half of the 18th century, as long as the struggle of Russia for control over the eastern parts of Poland continued. Several examples are reproduced in Gębarowicz, Mater Misericordiae-Pokrow-Pokrowa, fig. 42; Pamiatky knyzhkovoho mystetstva, nos. 780, 2857; Alekseeva, M. Graviura petrovskogo vremeni (St. Petersburg, 1990), 10–11. See also Krivtsov, D. Iu. "Obraz dvuglavogo orla v simvolike zapadnorusskikh posviatitel’nykh predisloviy XVII — nachala XVIII vv. (na materialakh izdaniia tipografii Kievopecherskoi Lavry," in Geraldika: Materialy konferentsii ‘10 let vosstanovleniia geral’dicheskoi sluzhby Rossii’ (St. Petersburg, 2002), 58–67. The copies of Gisel's image of the double-headed eagle in central Russia were often stripped of the political connotations relating to the encounter of the Eastern Orthodox Christians with the Polish Catholics. For example, the icon painter Semen Ivanov of Ustiuzhna near Vologda (fig. 10) placed under the eagle's arrow and palm branch a pair of identically recumbent worshipers rather than the two conflicting troops, and depicted the apostles and evangelists instead of the Kyivan saints, see Ufi Abel and Vera Moore, Icons (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2002), 128–129. On this iconography, see also Tarasov, Oleg. Icon and Devotion: Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), 277–80.

[20] Raba, Joel. Between Remembrance and Denial: The Fate of the Jews in the Wars of the Polish Commonwealth During the Mid-Seventeenth Century as Shown in Contemporary Writings and Historical Research (Boulder, CO and New York: East European Monographs, 1995), pp. 37ff, 67ff, 139. See also: Mintz, Alan. Hurban: Responses to Catastrophe in Hebrew Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 102–105; Shmeruk, Chone. "Yiddish Literature and Collective Memory: The Case of the Chmielnicki Massacres," Polin, 5 (1990): 173–83.

[21] This view of the massacres appears to be denoted by the plea of Jews in the hour of danger as described by Meir ben Samuel from Szczebrzeshyn: "We will give our lives for the holiness of our Lord, […] and may be then we desert [God's] grace," Meir b. Samuel of Szczebrzeszyn, Tsuk ha-Ettim (Cracow, 1650) (Hebrew). See: reprints in H. J. Gurland, Le-Korot ha-Gezerot al-Yisrael, 4 (Cracow, 1889), 115 (Hebrew); Rosman, M. Texts on the Massacres of the Years 1648–1649: Meir of Szczebrzeszyn, N. N. Hannover (Jerusalem: Merkuz Dinur, 1981), 6.

[22] This approach is found in the Bible. For example, Ezekiel prophesied that God does not desire the destruction of sinners, but rather that through repentance they may live (18:23). See also: Exodus 34:6–7; Hosea 11:9.

[23] Gurland, H. J. Le-Korot ha-Gezerot al-Yisrael, 1 (Cracow, 1887), 10; Raba, Between Remembrance and Denial, 70. Note also the concluding sentence of Nathan (Nata) Hannover's popular chronicle of the Khmelnytsky (Chmielnicki) massacres Yeven Metsulah (literally, "Deep Mire" and figuratively, "Abyss of Despair") first published in Venice in 1653: "the Lord should hearken to our cries and gather our dispersed 'from the four corners of the earth' [Isaiah 11:12], and send us our righteous Messiah, speedily in our day," Hanover, N. Abyss of Despair (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1983),121. See also: Rosman, Texts, 44, and similar excerptions in Raba, Between Remembrance and Denial, 70.

[24] Breyer [Breier], A. "Die hölzernen Synagogen in Galizien und Russisch-Polen aus dem 16., 17. und 18. Jahrhundert" (Ph.D. thesis, Vienna 1913), 13; Breier, A. Eisler M., and Grunwald M., Holzsynagogen in Polen (Baden bei Vienna, 1934), 9–10.

[25] On the hare as an allegory of the Jew in medieval Jewish art, see: Pasquini, Laura "The Motif of the Hare in the Illuminations of Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts," Materia giudaica 7, no. 2 (2002): 273–82.

[26] This reading was proposed by Andrzej Wierciński, "Orzeł i zając: Próba interpretacji plafonu sufitowego synagogi w Chodorowie" in Żydzi i Judaizm we współczesnych badaniach polskich. Materiały z konferencji, Kraków 21–23 XI 1995, ed. Krzysztof Pilarczyk (Cracow: Księgarnia Akademicka Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1997), 376. See more argumentation in Elliott Horowitz, "Odd Couples: The Eagle and the Hare, the Lion and the Unicorn," Jewish Studies Quarterly, 11 (2004): 243–58.

[27] Rovinskii, Russkie narodnye kartinki, 40; Belobrova, O.A. "K istorii knizhnoy miniatiury i narodnoi kartinki kontsa XVII — pervoi poloviny XVIII vieka," in Narodnaia kartinka XVII-XIX vekov (St. Petersburg, 1996), 71–81.