The Ukrainian question in the world perception of Jabotinsky the Zionist

Copyright © 2021 RFE/RL, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

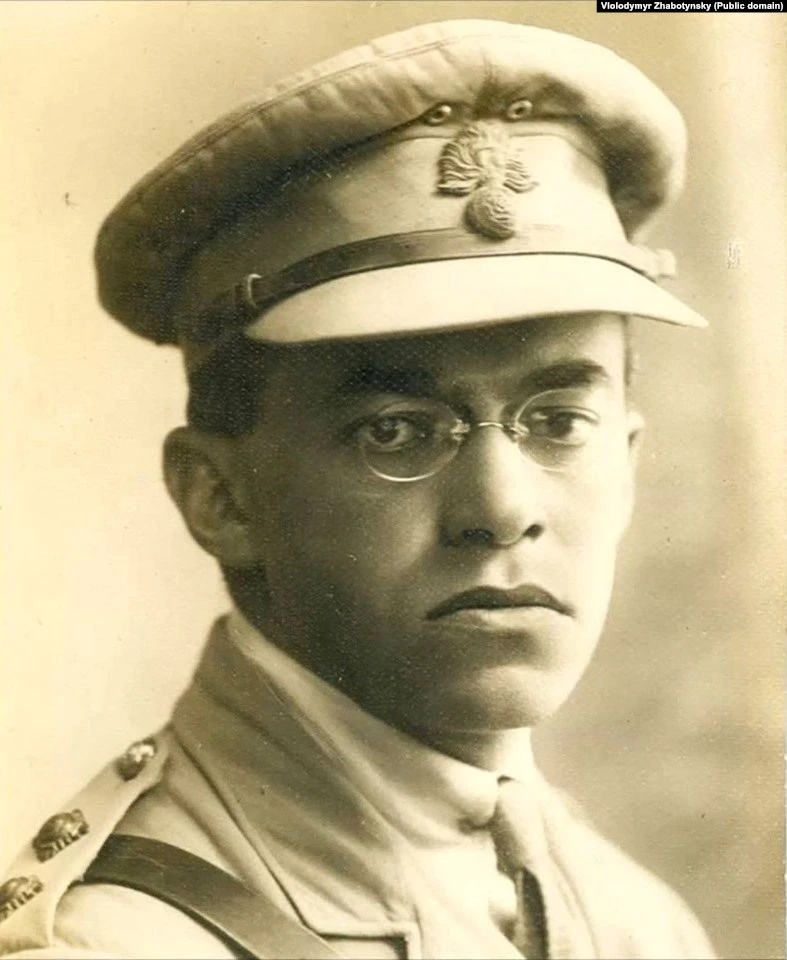

He was born in Odesa, studied in Switzerland, Italy, Austria, France, and Palestine, and died near New York City. In keeping with his Last Will and Testament, he was reburied on Mount Herzl twenty-four years after his death. He witnessed anti-Jewish pogroms at the beginning of the twentieth century, experienced the First World War, and saw the beginning of the Second World War. He could have carved out a brilliant career for himself as a journalist, writer, or lawyer, but chose the path of a revisionist Zionist and political leader of the Jewish people, and for a time, he was a soldier in a battalion of the Jewish Legion. The sixty-year-long life of Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky (1880–1940) was packed with various activities.

Jabotinsky fought for the creation of the State of Israel and was positively disposed toward the idea of the national and cultural development of all peoples within the framework of a sovereign state. In this regard, the public discussion of the "Ukrainian question" between Ze'ev Jabotinsky and Petr Struve, a member of the Russian Constitutional Democratic Party (Cadets), historian, and essayist, is little known. Struve consistently promoted the thesis of a "single Russian nation."

During the course of his polemic with Struve, Jabotinsky published several articles. The consummate ones, in the view of Jabotinsky specialists, are "The Lesson of the Shevchenko Jubilee" ["Urok iubileia Shevchenko" was published on the fiftieth anniversary of Taras Shevchenko's death in the newspaper Odesskie novosti [Odesa News] on 27 February 1911—Ed.], "The Falsification of a School," "On Language and Other Matters," and "Struve and the Ukrainian Question."

For example, in challenging Struve's question, "Are Ukrainians part of the Russian nation or a separate nation," Jabotinsky emphasizes in "The Lesson of the Shevchenko Jubilee" that "it is crucial to understand, recognize, push through, and grant a lawful place to the mighty brother, second in strength in this empire—the Ukrainian people."

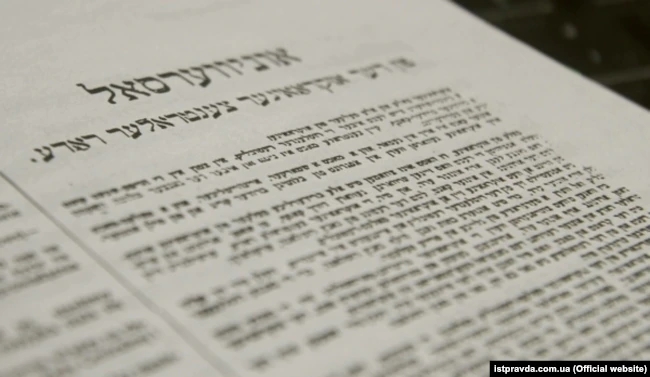

"It may be stated boldly that this series of articles is unprecedented in world journalism as an example of the protracted struggle of the representative of one people for the national rights of another people—a struggle that grew in size to a whole press campaign." This quote is from the introduction to the collection Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky: Selected Articles on the National Question, by Israel Kleiner, one of the most well-known researchers of his legacy.

The figure of the researcher is no less interesting. Israel Kleiner, a native of Kyiv, wrote material that was broadcast in the 1970s by the Voice of America and Radio Liberty. After he immigrated to Israel, he continued to work in journalism and was employed at the Jabotinsky Institute in Tel Aviv.

In his collection, Kleiner included ten articles that characterize most broadly Jabotinsky's civic and political position on both the Ukrainians and the national question in general. Kleiner's 1980 monograph, Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky and the Ukrainian Question appeared in the Ukrainian language in 1995.

As Kleiner reveals in his work, Jabotinsky called for mutual understanding with the Ukrainian national movement, a position that derived from his own principled convictions that within the bounds of one empire, the peoples oppressed by it have a common enemy and a shared national goal. Such convictions were most definitely out of step with the times. In his 1906 article "Non multum, sed multa" [Not many, but much—Trans.], the young Jabotinsky expressed himself thus: "Each going their own way, they [Ukrainians and Jews—Ed.] can help one another today."

As Kleiner reveals in his work, Jabotinsky called for mutual understanding with the Ukrainian national movement, a position that derived from his own principled convictions that within the bounds of one empire, the peoples oppressed by it have a common enemy and a shared national goal. Such convictions were most definitely out of step with the times. In his 1906 article "Non multum, sed multa" [Not many, but much—Trans.], the young Jabotinsky expressed himself thus: "Each going their own way, they [Ukrainians and Jews—Ed.] can help one another today."

According to Kleiner, Jabotinsky, thanks to his political sense, learned early on in his life that the "Ukrainian question is the key problem that will determine, to the greatest extent, the future of the Russian Empire and thus the fate of the Jews on its territory."

Another detailed biography of "Jabo," as Jabotinsky was called by his close friends and associates, was written in the early 2000s by the Israeli writer and journalist Shmuel Katz. There is a play on words in the title of his book, Lone Wolf, A Biography of Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky: in Hebrew, the name Ze'ev means "wolf."

As concerns his lone state, despite his fame and significant group of supporters, quite a few members of the Zionist movement criticized Jabotinsky and occasionally expressed hostility toward him. Katz called Jabotinsky "the most slandered Jewish leader." Also, thanks to a plethora of Marxist-Leninist works, the word "Zionist" was negatively branded along the following lines: "Zionism is an anti-Soviet, chauvinistic, reactionary ideology and policy of the Jewish bourgeoisie."

Even in Odesa, the city where Jabotinsky was born and where he launched his creative activities and where dozens of addresses are associated with him, there was a veil of silence around his memory for decades, until the early 1990s, when his most famous work, the novel The Five, was returned to the city.

Jabotinsky's treatment of the Ukrainian question: three periods

Kleiner singles out three periods during which Jabotinsky consistently addressed Ukrainian issues.

The first period: 1904–1914

Jabotinsky is published in the Russian-language newspaper, Ukrainskii vestnik [Ukrainian Herald], which came out in St. Petersburg with the collaboration of Mykhailo Hrushevsky. He writes for the Moscow-based journal Ukrainskaia zhizn′ [Ukrainian Life], and conducts a discussion in various newspapers with Struve, which became part of the convinced Zionist's broader considerations of questions regarding the rights of national minorities.

The second period: 1917–1921

When Jabotinsky devoted special attention to the "Ukrainian question."

This was a period marked by the dynamic development of the Zionist movement and the popularization of the idea of Jewish immigration to Palestine, on the one hand, and the proclamation of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), on the other.

There is a particularly historical detail that is fascinating in that it has no analogues in world history. One of the executive departments of the Central Rada was the General Secretariat of Jewish Affairs. When the UNR was proclaimed, the secretariat became a ministry. The first serious research on the Ministry of Jewish Affairs and Jews in the Central Rada was written by the University of Toronto professor Henry Abramson, author of the book A Prayer for the Government: Ukrainians and Jews in Revolutionary Times, 1917–1920.

In 1917 Jabotinsky became an officer of the Jewish Legion, which was part of the British army. In 1940, a few months before his death in the U.S., where he was living, he wrote that he was cheered by the news that a Jewish army that would be fighting against the Nazis on the side of the Allies was being planned.

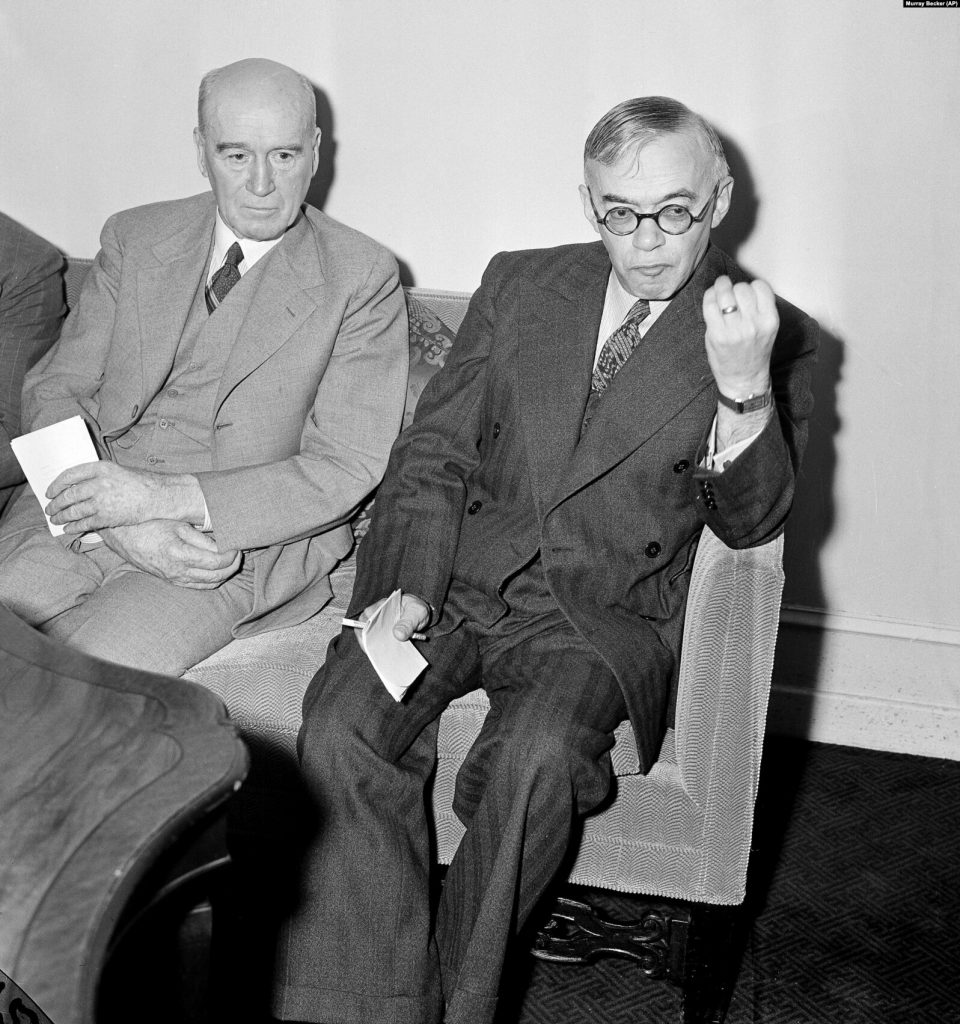

At the Zionist congress in Carlsbad in 1921, Jabotinsky and Maksym Slavynsky, the representative of the special diplomatic mission of the Ukrainian National Republic's government-in-exile (who had been Jabotinsky's colleague in the editorial offices of the newspaper Russkie vedomosti [Russian News]) reached an agreement about creating a Jewish gendarmerie in the Army of the UNR. It would be used to counteract possible pogroms and would enjoy some autonomy, but from the moment it entered Soviet-controlled territories, it would shift to supporting the Ukrainian government.

This was precisely when Jabotinsky, who had been harshly criticized by certain representatives of Jewish circles, said famously: "When I die, you can write on my grave: 'This was the person who signed an agreement with Petliura'" (the two men did not know each other personally—Ed.)

This agreement was never realized because Symon Petliura was assassinated in Paris in May 1926. Shortly afterwards, Jabotinsky told the New York-based Jewish Morning Journal: "Neither Petliura nor Vynnychenko or the rest of the distinguished members of this Ukrainian government were ever people who could be called 'pogromists.' [...] I know well this type of Ukrainian nationalist intellectual with socialist views. I grew up with them; together with them, I conducted a struggle against antisemites and Russifiers—Jewish and Ukrainian. No one will convince either me or other thinking Zionists of southern Russia that people of this type can be regarded as antisemites."

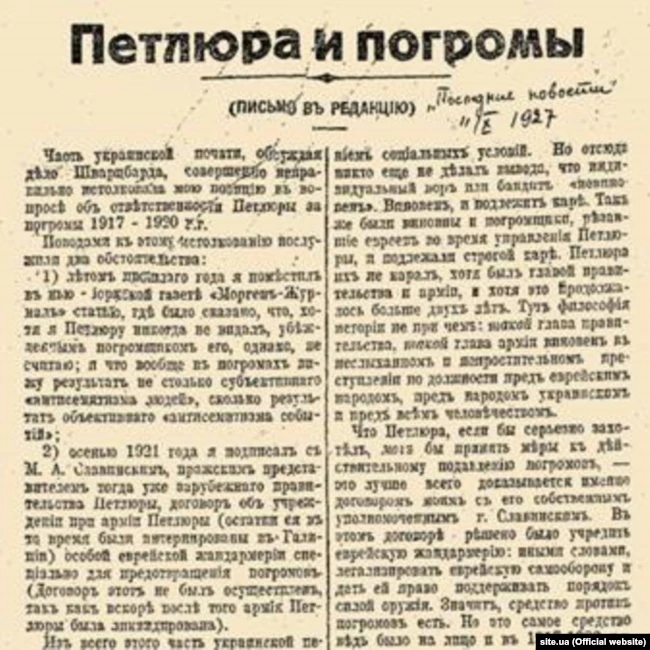

It is true, however, that a year later, in 1927, Jabotinsky stated the following in a letter to the editorial offices of the Russian-language Paris newspaper Poslednie novosti [Latest News] "Part of the Ukrainian press incorrectly interpreted my position on the question of Petliura's responsibility for the pogroms of 1917–1920."

In a subsequent article entitled "Petliura and the Pogroms," he explained that he was not accusing Petliura and the Ukrainian national movement either of antisemitism or of organizing pogroms, only their inability to halt them: "Dismissing it [responsibility] means not understanding what it is to be the head of the government and the army."

Jabotinsky concludes his article with an appeal for cooperation between the Jewish and Ukrainian national movements: "I remain a friend of the Ukrainian movement. Furthermore, I will continue to strive for concord with the Ukrainian movement."

The Third Period: 1925–1927

Biographers and researchers believe that the third period of Jabotinsky's active engagement with the Ukrainian question dates to 1925–1927 and that it was directly connected with Jewish agricultural colonization introduced by the Soviet government. The Soviet Union's policies at the time envisaged engaging the Jewish population, which had been deprived of its earnings in cities during the Civil War, in working the land.

"In its pursuit of loans, the Soviet government is seeking constant sympathy from circles of the foreign bourgeoisie, and it very much values the attitude of the foreign Jewish bourgeoisie," he warned Ber (Borys) Brutskus, an economist, agronomist, and civic activist dispatched by Lenin, in an article entitled "The Jewish Population under Soviet Rule."

Jabotinsky was categorically opposed to the plans for Jewish colonization, emphasizing its anti-Zionist orientation and provocative nature with regard to the Ukrainian peasantry. Jabotinsky laid out in scrupulous detail his position on the project of Jewish colonization in the USSR in an article entitled "Crimean Colonization" (1926).

Jabotinsky's position on the Ukrainian question was a manifestation of his general world perception with regard to national minority rights, which were reflected in a more concentrated fashion in two sources: the 1906 Helsingfors (Helsinki) Program, of which he was very proud ("The peak of my Zionist youth was the Helsingfors conference," he writes), and his little-known dissertation for the Candidate degree entitled "Self-rule of National Minorities in Areas with a Diverse Population" [He defended his scholarly work for the degree of Candidate of Juridical Sciences in 1911—Ed.].

The rare typescript of the article "Self-rule of National Minorities," which runs to thirty-two pages and includes fragments of Jabotinsky's future dissertation, is discussed in the book The Jewish People's Lawyer, which was published in Odesa in 2019.

"’Self-rule of National Minorities’ echoes the Helsingfors Program, a set of resolutions of Zionist conferences that took place in the early years of the twentieth century. The article contains thoroughly modern theses about the right to the independent conduct of national affairs by national minorities,” says Professor Tymur Korotkyi, one of the co-authors of the book.

What does Jabotinsky’s native city remember about him?

Odesa, where Jabotinsky was born in 1880, was called “the Gates of Zion” (Shaarei Zion in Hebrew). From the second half of the nineteenth century, the city became known as one of the main centers of Zionism in the Russian Empire. Literature in Hebrew was published here, and it was the place from where Jews headed to Palestine.

“In Odesa, Jabotinsky matured in the milieu of distinguished personalities, whose creativity, knowledge and worldview influenced the man that he became. Alongside him lived and worked poets, writers, and the historians Hayim Nahman Bialik and Yehoshu‘a Ravnitski, Leon Pinsker and Ahad Ha-Am, Mendele Moykher-Sforim and Sholem Aleichem, Yosef Klausner and Sha’ul Tchernichowsky,” noted the Israeli diplomat and culturologist Dr. Yatvetsky in his commentary for Radio Liberty.

When the future Zionist was living in the building pictured above, located at 1 Yevreiska Street, he was still just a talented young man. He had just begun working as a journalist for the newspaper Odesskii listok [Odesa Leaflet], but he was already recognized as the author of the finest Russian-language translation of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem, “The Raven.”

“This is the so-called Doks apartment building. It was built in 1886–1887 (various sources list different dates). Jabotinsky lived there from 1897 to 1904. One old-timer by the name of Semyon Abramovich, with whom I often communicate, believes that he lives in the attic room where Jabotinsky once lived and which he described in the novel The Five. He says that the description fits. At the same time, historians are convinced that Jabotinsky lived in apartment no. 12 on the second floor,” as Eduard Stas, one of the developers of the municipal program for the preservation of the city’s historic center, told Radio Liberty. Stas has an excellent knowledge of nearly every historic building in downtown Odesa, not just because this is his electoral district, but also thanks to his passion for local lore: “The building, like quite a few others in downtown Odesa, is not in very good shape. But some authentic elements inside have been preserved, for example, the cast-iron staircase leading to the attic.

But the most galling thing is that the high relief that was installed on the building in 1997 with the participation of Jabotinsky's grandson and great-granddaughter has been lost. A few years ago, one of its upper elements was stolen, and in May of last year, the entire high relief disappeared. Joel Lion, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the State of Israel to Ukraine, even sent an open message to the then head of the Office of the President and to the Odesa municipal government, requesting that efforts be taken to track down the thief.

Regrettably, nothing was done.

Pavlo Kozlenko, director of the Holocaust Museum in Odesa, recounted that a few years ago, attempts were made to purchase an apartment in the building at 1 Yevreiska Street and create a small museum dedicated to Jabotinsky. The residents did not support the idea and, according to Kozlenko, it is not 100-percent sure which apartment Jabotinsky occupied for seven years in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries.

“...In the fall of 1919, a ship set sail from the Port of Odesa with 600 repatriates on board. A few weeks later, they reached the Port of Jaffa in Palestine, their arrival thus turning the page on the brilliant Odesa Zionist page. Four years earlier, in 1915, Ze'ev Jabotinsky forever left his native city. Two decades later, in his novel The Five, he would write with undisguised nostalgia: “It is incredible that I will never see Odesa again. A pity. How I love it!”

Jabotinsky on language, nation, and state

“The inner life of every nation, like before, will be incarnated with the help of its national language, and this language will develop in an original way and become enriched through the evolution of the nation” (“Critics of Zionism,” 1905).

“He [Shevchenko] gave both his people and the world brilliant, unassailable proof that the Ukrainian soul is capable of the highest flights of original cultural creativity. [...] Shevchenko will always remain as he was created by Nature; a blinding precedent that does not allow Ukrainians to stray from the path of their national renaissance” (“The Lesson of the Shevchenko Jubilee,” published in Odesskie novosti in 1911).

“I consider myself fundamentally the same master in this state [Russia] as the Russian: I want to speak, study, write, and be judged in my national language; I have no intention to adapt myself to anyone. Instead, I demand that the state adapt itself to my national demands, just like it must adapt itself to the demands of Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Tatars, etc.” (“On the Wrong Path”], 1912).

“Language, which was born together with a people, will remain with it in one form or another for the entirety of its path—the national language” (about the Hebrew language in the article “The Ideology of Betar,” 1934).

Streets have been named after Jabotinsky in fifty-five cities in Israel. “Of all the distinguished personalities whose names are reflected in the names of Israeli streets, he is the most popular,” says Dr. Yatvetsky.

The journalist, essayist, and political commentator Vitaly Portnikov regards Jabotinsky as a “prophet-like” figure. “He was an extraordinary personality, and his personality changed throughout his life. The most important change in Jabotinsky’s consciousness was the Kishinev pogrom [1903; one of the bloodiest pogroms in the Russian Empire—Ed.] when the Russian writer and journalist turned into a passionate supporter and propagandist of Zionist ideas.”

Moreover, he was one of the first Zionist activists who put words into action, that is, to organize people who would protect Jews and, over time, rebuild the future State of Israel.

Regrettably, he did not live to see the emergence of an independent Israel.

Similarly, he believed that the Ukrainian people would definitely manifest their desire for statehood. He wrote about this in his works; he even predicted the appearance of Ukrainian signs on shops in Odesa, which in his time was regarded as science fiction.

Jabotinsky’s attitude to the Ukrainian people was that they had the right to statehood. This is a simple axiom: If you defend the Jewish people's right to their statehood, how can you deny the right to statehood to others? From this standpoint, Jabotinsky was indeed a prophet-like figure in our contemporary context. One important lesson that he left for today’s Ukrainians is that if you see something that does not suit you, then you must act, become a participant, not just an observer.

Iryna Nazarchuk

Iryna Nazarchuk

I have been writing and filming for the Ukrainian Service of Radio Liberty since 2017. My article “Despite Stereotypes: Women in the Navy” was the winning submission of the United Nations’ competition for journalists called Publications for Changes: Ukraine on the Path to Sustainable Development. I graduated from Odesa National University and have worked at radio and television stations as well as information agencies in Odesa. I completed several training courses at Internews Ukraine.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian @Radio Svoboda

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.