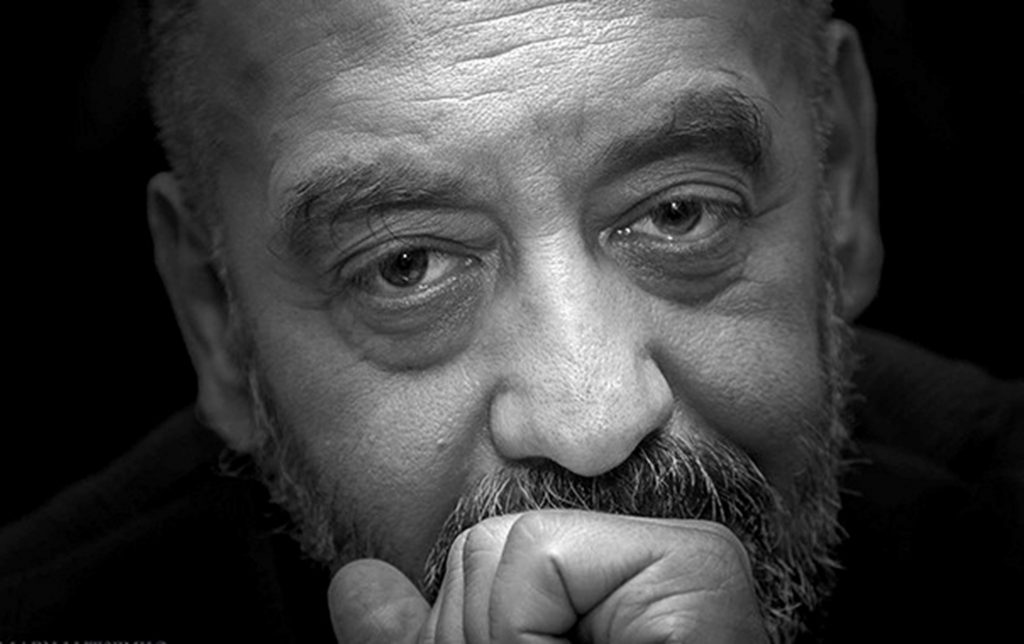

There may have been antisemites at the Maidan but there was no antisemitism: artist Matviy Vaisberg

[Editor’s note: In honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we are running a two-part series with famed Kyiv-born artist Matviy Vaisberg that aired on Hromadske Radio in 2020. The second part of the interview discusses the life of a Jewish family in Kyiv in the 1960s.]

We are continuing our conversation with the artist Matviy Vaisberg.

Vasyl Shandro: We begin our conversation with “Jewish Kyiv,” the one that you remember: the second half of the twentieth century. What are your thoughts about the coexistence of people of very different nationalities, religions, and ideological views who practically did not speak out publicly?

You lived and are still living in the so-called “writers’ building” (RoLit House). Was this a multinational building in your memory?

Matviy Vaisberg: Yes. Besides the great Ukrainian writers and poets—Malyshko, [Oles] Honchar, [Volodomyr] Sosiura, and [Pavlo] Tychyna— [Dovid] Hofshteyn, Riva Baliasna lived there. A kind of Ark.

Vasyl Shandro: What did it mean to be a child from a Jewish family living in Kyiv in the 1960s?

Matviy Vaisberg: There may be several aspects here. Let’s say, in my class at the regular school, high school no. 35, thirty percent were Jews. Now the whole class has left, not just Jews, and that’s bad because they were not the stupidest people of my generation.

I had an indirect relationship with the purely Jewish world. For example, my grandmother would go out and talk with her girlfriends in Yiddish. I really laughed at the time, but now I am sad that I don’t know this language; sometimes something pops out. I knew that I was a Jew—always. To be honest, there was a lot of everyday antisemitism. I want there to be truth always, no matter what it is. Truth heals. That’s how it was, no matter how shameful that is.

I remember all these jokes about Abraham and Sarah, and all this was truly terrible. You know, when it turned out that at the age of ten my son, Simon Vaisberg, does not know the word zhyd, I realized that something had changed. When I enrolled at the institute, I knew I had the “fifth paragraph” [declaration of nationality]; it was 1977. Quite a few people went to enroll in small towns, including in Russia, which is interesting. I finally got in, but I remember how my mother “fought,” making deals with someone.

In her day, Mama got in because [Mykola] Bazhan spoke up for her; he telephoned the institute. Mama was shielded from some historian who was the Jews’ principal opponent. For him, a word from Bazhan was no ukase. Mama passed her exam for a different lecturer and enrolled in Art History.

Vasyl Shandro: Was there some sort of impersonation?

Matviy Vaisberg: There was mimicry. Quite a few people changed their surnames, and that worked. I would never do such a thing, but I don’t blame those who did such things. People wanted to obtain a higher education, to adapt, to survive. For me this was unacceptable.

What other markers do I have if I am Matviy Semenovych Vaisberg? As my mother used to say when I did something wrong before the entrance exams, “You’re limping on your fifth leg!”

Vasyl Shandro: In a recent interview Yosyf Zissels expressed the opinion that the concept of “Ukrainian Jew” may have appeared in the 1990s when the Ukrainian state emerged. Did you see any contradictions in the concept “Ukrainian Jew” or “a Ukrainian and a Jew”?

Matviy Vaisberg: I am not entirely in agreement with Zissels. Still and all, my grandfather, a poet who wrote in Yiddish, was more involved in the Ukrainian environment. This was the “Ukrainian wave”; a lot of writers, including Jews, also took part in it.

My father very much disliked chauvinism; he believed that all troubles stem from it. Various people came to our house, including Ukrainian-speaking ones. So, I had some preparation.

The most important thing here is the degree, so to speak, of fairness, when you feel the splitting of that empire and the birth of a new country. When the first referendum took place “in favor of the Soviet Union” or “against,” I did not go. But I went to the second referendum, in favor of separation, and voted. It was a gradual thing; I’m that way too, in fact—in art as well. Perhaps I make gradual progress, but I think that it is evolutionary.

Vasyl Shandro: Propaganda was still at work during the Soviet period as well as in the 1990s, in the 2000s, and today. How did you coexist with these histories about [Stepan] Bandera, [Roman] Shukhevych, the UPA, or did this pass you by?

Matviy Vaisberg: I still believe that we should say what really happened. There were various things, and I cannot say that everyone was white and fluffy; intellectual honesty does not permit me to say this. There were such things from all sides.

I believe that we should write the truth about everything and that this not be done by imperialists or the media. We are generally the ones who need this. I have revised quite a lot of my views. I too clung to some stereotypes, why ever not? I am a person who was raised in the Soviet Union.

We need to speak about the Zolochiv pogrom, about the Lviv pogrom; about the way it was. Then all of us—Ukrainians, Jews, Ukrainian Jews—will be speaking this healing truth, no matter how difficult it was.

With respect to our times: there may have been antisemites at the Maidan, but there was no antisemitism. Do you understand? There simply was none! When someone wrote Het vladu zhydiv (“Down with Jewish power!”) on the TsUM [Central Department Store], that same day my friend, Dmytro Desiateryk, went home, grabbed some paint, and painted out the word zhydiv, leaving Het vladu (“Down with the government!”). We must talk about this. The main thing is the people’s reaction, not the fact of this inscription.

This program is created with the support of the Canadian charitable non-profit organization Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.