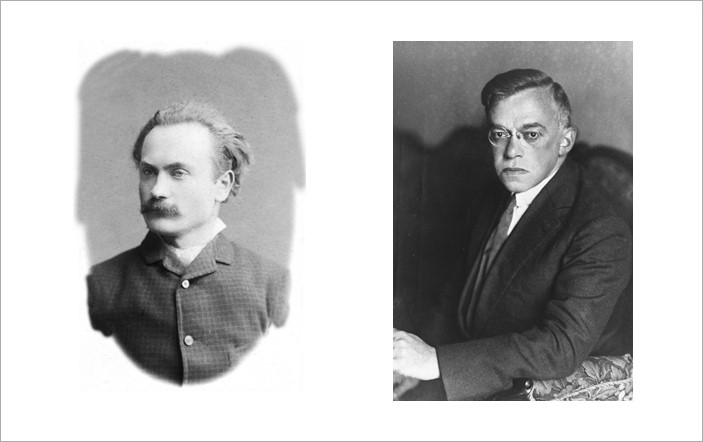

Two views on Ukrainian-Jewish relations: Franko and Jabotinsky

Both men hailed from the territory of modern Ukraine. Both were influential journalists, writers, and thinkers during their lifetimes. Both remained inspiring figures for generations to come. But they were different in one distinct way. This is a shorter version of an article by Wolf Moskovich published in the book “Ivan Franko und die jüdische Frage in Galizien” (“Ivan Franko and the Jewish Question in Galicia”).

This essay originally appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of The Odessa Review, which was supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

This essay originally appeared in the October/November 2017 issue of The Odessa Review, which was supported by the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.

Ivan Franko (1856-1916) was Ukrainian. Among the Ukrainian intellectuals of his time, he was unique for his deep understanding of the Jewish people and its cultural tradition. Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), by contrast, was Jewish. No Jewish leader before or after him paid so much attention to Ukrainian national issues and to solving the so-called “Jewish question” in Ukraine.

Franko was ambivalent in his relation to the Jews. Some of his statements and characterizations of Jews can be considered philo-Semitic, while others can be seen as antisemitic. His positions on the Jewish question shifted with time and according to circumstances and his audiences. In contrast, Jabotinsky’s position on the Ukrainian-Jewish relations and his support of the Ukrainian national struggle remained permanent through his life. His writings show only a positive attitude towards Ukrainians.

But more than anyone else, these two men attempted to cross the Ukrainian-Jewish divide in their respective societies. They helped to sow seeds off cooperation on distinctly infertile soil. Yet their efforts embody both the successes and failures of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.

Franko: Ukrainian Zionist?

Throughout his life, Ivan Franko based his position on Ukrainian-Jewish relations upon his defense of the economic interests of Ukrainian peasants and workers in Austrian-controlled Galicia. As a Ukrainian radical and a nationalist, he acknowledged the national rights of the Jewish minority in Galicia. But he also demanded that the Ukrainian peasantry and working class be protected from Jewish exploitation.

Unlike many of his Ukrainian contemporaries, Franko deeply understood the various facets of Galician Jewry and the problems surrounding it. Yet he also regarded the mass of 800,000 poor, black-clad Hassidim, who made their living as petty merchants and tavern keepers, as parasites exploiting Ukrainian peasants, who were themselves even poorer. On the other side of the social divide, he saw Jewish industrialists and bankers, the owners of enterprises where those exploited Ukrainian workers were employed. And in the middle there were assimilated Jews, who were either Polonized or Germanized, and had little contact with the Jewish proletariat.

Franko supported the recognition of Jews as a separate nation — with full equality of rights and obligations. In his view, Jews could either assimilate, emigrate or remain in Galicia as aliens without the right to possess or farm the land. Because the Jewish community showed strong cohesion and solidarity in protecting the economic interests of its members, Franko believed it necessary for Ukrainians to defend their economic position by creating cooperative institutions that would eventually eliminate the Jewish middlemen. He saw a particular danger for the Ukrainian peasants in the campaign by the ‘Alliance Israelite’ that sought to bring Jewish colonists from the Russian pale of settlement to Galicia. He warned the Austrian authorities that uncontrolled settlement in Galicia of thousands of Jewish paupers from Russia might cause a catastrophe that he wished neither the state nor the Jews.

But Franko was also presumably the first non-Jewish reviewer of Theodore Herzl’s book Der Judenstaat. His sympathy toward the Zionist idea originated from the realization that the dire economic conditions of Ukrainians in Galicia, which he rationalized as Jewish exploitation, demanded the emigration of Jews as a safety valve. At the same time, Herzl’s idea of a national state for Jews stimulated his own dreams of an independent Ukrainian state. He did not consider these plans realistic for his times. As for the future, their realization could be achieved by the will of the Ukrainian people.

Franko did not support any Jewish assimilation in Galicia that strengthened the Polish hold on the province. For some reason, he wrote, Jews had a tendency to assimilate to the more powerful nation closest to them, but not to the poorer one, the oppressed one.

Why there are no Ruthenian (i.e. Ukrainian) Jews? — asks his Jewish protagonist Vagman in the novel ‘Crossroads.’ We forget, confirms Vagman, that more than half the Jewish people live now on Ruthenian soil, and the Ruthenian hatred, accumulated over the centuries, may burst into such a flame and assume such forms that our protectors, the Poles and the Russians, will be unable to help us. Vagman calls for efforts to reach an understanding with the Ruthenian peasants. As soon as they advance a little and attain some strength, says Vagman, more and more Jews will begin to shift to their side. But it is important to assist them now, when they are still weak, downtrodden and unable to strengthen up.

In other words, despite his negative assessment of the Jewish role in Galicia, Franko articulates a positive program for the Galician Jews: to remain a Jew and yet love the country where he was born, and be useful, or at least not harmful to Ruthenians. No assimilation is necessary.

This vision was not purely theoretical. When a real representative of such a rare type of Jew appeared on Franko’s horizon, he warmly accepted and supported him — for example, the Ukrainian poet Hryts’ko Kernerenko (Grigory Kerner, 1863–1920’s?). During 1904–1908, Franko printed over ten of Kernerenko’s publications, most of them translations from Yiddish of works by Simon Frug and Sholem Aleichem, in a magazine he and Mykhailo Hrushevsky edited. In the same magazine, Franko published his own translation of the Yiddish poet and folklorist Wolf Ehrenkranz. Franko, who apparently knew Yiddish from childhood, also occasionally published his own translations of the Yiddish folk verses.

Jabotinsky: Sympathizer of the Ukrainian National Cause?

Between 1904 and 1914, Vladimir Jabotinsky wrote many articles on Jewish-Ukrainian relations.

He began to cooperate with the journal Ukrainsky Vestnik (“The Ukrainian Herald”), edited by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, in 1906 and with Ukrainskaia Zhizn (“Ukrainian Life”), edited by Symon Petliura, in 1912.

When Jabotinsky was starting his political career, Ukrainian-Jewish political cooperation largely did not exist. He began to work incessantly — against the unwillingness of Jewish circles — for the cause of Ukrainian and Jewish national forces’ cooperation.

The fact that Ukrainian democratic parties had a positive attitude toward Jewish national aspirations was a major factor for doubling his efforts. Jabotinsky saw similarities in the national destinies of both peoples. Both strove to preserve their national identities despite lacking their own states and facing oppression. As the author of the so-called Helsinki program adopted by the Zionist Organization in 1906, Jabotinsky advocated for the democratization of Russia on the basis of national autonomy, parliamentarism, and the acknowledgement of full national rights for national minorities.

Jabotinsky saw the Ukrainian national movement as the Jews’ natural ally in the fight to achieve this democratization. The future of the Russian empire, Jabotinsky wrote, depended upon the direction in which Ukraine would turn. To become democratic, Russia had to become a nation state. Ukrainians had to be given territorial and cultural autonomy. In his polemics with Russian Constitutional Democrat Pyotr Struve — who did not consider Ukrainian to be a language distinct from Russian — Jabotinsky asserted that Ukrainians have a separate self-consciousness, which for him was sufficient reason for Ukrainian to be considered an independent language.

Jabotinsky called on the Jewish national movement not to ignore the rising Ukrainian national-liberation movement. Jewish assimilation into the dominant Russian culture, their identification with Russian imperialist forces, their political blindness in face of a developing Ukrainian nationalist drive might have dire consequences for them in the future, Jabotinsky predicted.

Time and again, Jabotinsky refers in his works to two kinds of antisemitism: the antisemitism of people (which is subjective) and the antisemitism of circumstances (which is objective). The latter is a result of the dispersion of Jews in foreign lands, and has as its source the instinctive enmity of any normal person toward ‘aliens.’ To Jabotinsky, this is an ineradicable consciousness in the heart of every non-Jew. While the social climate is quiet, this does not hurt normal neighborly relations, even friendship. But in situations of social tension it bodes disaster for Jews. The circumstances in Galicia, wrote Jabotinsky, were against the Jews. Therefore, the only viable solution for Galician Jews that remained was to return to Zion and create a national state in Palestine.

Some of Jabotinsky’s pronouncements were not acceptable for other Jewish leaders. He drew the sharpest criticism for signing the Jabotinsky-Slavinsky agreement in 1921, which promoted the formation of Jewish self-defense units in the Petliura army. Jabotinsky tried to put himself right with his Jewish critics, but to no avail. Nevertheless, under Jewish public pressure, he declined the offer to appear at the trial of Petliura’s assassin, Shalom Schwartzbard, to testify that Petliura was innocent of the pogroms.

After the trial, Jabotinsky ceased to write on Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Jabotinsky considered his attempt at reaching cooperation with the Ukrainian national liberation movement his great achievement, the value of which would only be appreciated after his death.

Different Backgrounds, Common Views

Despite their differences, Franko and Jabotinsky’s approaches shared common features.

Both supported the democratization of Ukraine and Galicia on the basis of national autonomy and parliamentarism, as well as the recognition of all national groups and minorities’ rights. Both advocated for the full legal equality of Ukrainians and Jews and back the recognition of Jews’ national rights as an autonomous nation. Both supported the right of Jews to develop in the direction which they consider appropriate, with recognition of the same rights for Ukrainians and Poles. Both disapproved of Jewish assimilation into dominant nations. Both believed Jewish emigration to Palestine was a necessary safety valve for lowering the tensions in Galicia and supported for the creation of a Jewish national state in Palestine. And both rejected Jewish colonization of Ukrainian lands.

Jabotinsky understood that due to the region’s history, it would be difficult to persuade Jewish leaders to cooperate with Ukrainians. He therefore stressed their common interests.

“I am not an optimist and I do not believe in ‘love’ between nations”, he wrote. “In particular I do not in any way conceal from myself the fact that a certain antagonism exists between the Jews and Ukrainians in Galicia, one that sometimes takes on uncivilized forms. I am certain that those uncultured forms will disappear with the growth of education, but tribal conflicts will persist until there are fundamental changes in the political and ethnographic map of the world and in the socio-economic system”.

“But I am not appealing here for love”, he went on to say. “I am stating that at this moment there is a concurrence of interests between Galician Ukrainians and Galician Jews. While each pursues an individual course, they can today assist each other. That is what needs to be done”. Jabotinsky proposed a concrete plan of action: joint efforts with the Ukrainian populists for the democratization and autonomy of Galicia.

Franko’s legacy is more complicated. In Jewish memory, he remained a philo-Semite who warned that democrats had to beware of antisemitism like an infectious disease. Franko demanded equal rights for Ukrainians and Jews and in his public and political life always stood up for Jews as a humanist and a liberal. But he also could be harshly critical of Jews. Still, like Jabotinsky, he is recognized as a major figure in establishing contacts between Ukrainians and Jews.

Wolf Moskovich is Professor Emeritus at Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a Board Member of the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter.