UJE to start serializing "Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence": Introduction and Chapter 1

Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is an award-winning book that explores the relationship between two of Ukraine’s most historically significant peoples over the centuries.

In its second edition, the book tells the story of Ukrainians and Jews in twelve thematic chapters. Among the themes discussed are geography, history, economic life, traditional culture, religion, language and publications, literature and theater, architecture and art, music, the diaspora, and contemporary Ukraine before Russia’s criminal invasion of the country in 2022.

The book addresses many of the distorted stereotypes, misperceptions, and biases that Ukrainians and Jews have had of each other and sheds new light on highly controversial moments of Ukrainian-Jewish relations. It argues that the historical experience in Ukraine not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together.

The narrative is enhanced by 335 full-color illustrations, 29 maps, and several text inserts that explain specific phenomena or address controversial issues.

The volume is co-authored by Paul Robert Magocsi, Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Northwestern University. The Ukrainian Jewish Encounter sponsored the publication with the support of the Government of Canada.

In keeping with a long literary tradition, UJE will serialize Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence over the next several months. Each week, we will present a segment from the book, hoping that readers will learn more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and how ethnic Ukrainians co-existed with their Jewish neighbors. We believe this knowledge will help counter false narratives about Ukraine, fueled by Russian propaganda, that are still too prevalent globally today.

Introduction

There is much that ordinary Ukrainians do not know about Jews and that ordinary Jews do not know about Ukrainians. There is even more that Jews and Ukrainians do not know about themselves. As for the general public, here again there is considerable ignorance about these two peoples who have lived together for more than a thousand years in the lands that today comprise the European country known as Ukraine.

To fill this gap, we decided to write a book telling the story of Jews and ethnic Ukrainians in a completely new and perhaps risky manner. We chose to construct a parallel narrative, looking at patterns of settlement, history, traditional culture, religion, language, publications, literature, theatre, architecture, art, music, the diasporas of both peoples and their role in the political life and society of contemporary Ukraine. In an attempt to make a long story short, we have tried to present through a streamlined narrative our vision of Ukrainian-Jewish co-existence in all these fields. We have told the story, leaving aside mutual accusations against Jews by Ukrainians and against Ukrainians by Jews. Put another way, we as authors have chosen to be narrators, not polemicists, although we do address certain polemical issues in the text inserts.

Writing separately, one of us concentrated on the ethnic Ukrainians, the other wrote mostly on the Jews, although in some cases we changed or supplemented each other’s role. While we sought to enlighten our readers about the distinct cultural profile and different historical destinies of these two peoples, what emerged from our parallel narrative was a single story in which ethnic Ukrainians and Jews displayed as many similarities as differences.

Such a statement may seem paradoxical, considering the popular perceptions and stereotypical images held by both groups. Ethnic Ukrainians quite often saw Jews as lackeys, whether of Polish magnates, Russian landlords, or communists; as exploiters of the poor Ukrainian peasant; and as landless and cunning opportunists. Jews, in turn, saw Ukrainians as rustic, violent, rebellious peasants responsible for the destruction of Jewish communities during the mid-seventeenth-century Zaporozhian Cossack uprising and the eighteenth-century haidamak revolts, for the pogroms in the 1880s and 1919, and finally as people who helped the Nazis perpetrate the mass murders of Jews during the Holocaust.

Yet once we told the story of ethnic Ukrainians and Jews together, quite a different picture emerged: that of two decidedly heterogeneous peoples with a shared narrative. Their story may be one of difference, yet it is one with many chapters of commonality in which both ethnic Ukrainians and Jews appear as multilingual, multicultural, mobile, and highly culturally productive peoples. By emphasizing internal complexity, our story proves that there is no such thing as “the Jews” and “the Ukrainians.” Stereotypes about a people can exist in the popular imagination, but they come to naught once one explores the concrete historical, linguistic, religious, cultural, political, and artistic reality behind these stereotypes. What we thought would be merely informative turned out in the end to be instructive.

The Jewish presence in today’s independent Ukraine is much different than it was in the past. Before World War II, Jews made up more than 15 percent of the population in Ukrainian lands; at present, they represent a mere 0.2 percent of Ukraine’s population. Yet the significance of the Jewish people cannot be conveyed in figures alone. In other words, the fate of some 100,000 Jews in today’s Ukraine is as important as the fate of all of the other peoples who comprise the country’s 45 million or so citizens.

This book was conceived by two historians of diverse origin who believe that knowledge and understanding of the Jews and ethnic Ukrainians as distinct peoples should replace the bias and prejudices through which for too long each people has imagined the other. In order to achieve the goal of mutual understanding, it would behoove each people to explore the other as a historical entity and as fellow human beings who are the carriers of a specific cuture, body of religious belief, language, and social values. To help in this process, we needed to delve into the concerns, phobias, strivings, sorrows, and hopes of individual ethnic Ukrainians and Jews before we would be able to say something about them as representatives of their respective ethno-national group.

Perhaps we can share with readers our understanding of the historical experience in Ukraine as one that has not only divided ethnic Ukrainians and Jews but also brought them together. While this book may not change perceptions, it may be a first step that will bring knowledge about Jews to ethnic Ukrainians and knowledge about ethnic Ukrainians to Jews. It may also be a welcome source of information for anyone interested in learning more about the fascinating land of Ukraine and two of its most significant peoples.

Chapter 1

The land and its peoples

Ukraine is territorially Europe’s second largest country. A land rich in natural resources, Ukraine has since prehistoric time attracted numerous peoples from Europe and Asia, all of whom came there in the hope of finding a better life. Among those peoples are ethnic Ukrainians and Jews, whose story is the subject of this book.

Physical geography

The present-day country of Ukraine covers about 232,200 square miles (603,700 square kilometers), roughly the size of Germany and Great Britain combined, or, in the North American context, the size of Arizona and New Mexico combined. Its 48.4 million inhabitants (2001) make Ukraine the sixth most populous of Europe’s forty-eight countries, after Russia, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

Ukraine’s landscape is not very complex. Most of its territory consists of lowland plains and plateaus that at their highest rise only to about 1,600 feet (500 meters) above sea level. Virtually the entire southern half of the country is flat steppeland that in the past had been covered by a wide variety of lush grasses and shrubs. The rich black earth (chornozem) of the steppe has for centuries allowed for easy cultivation and incredibly productive harvests of a wide variety of grains (especially wheat), fruits, and vegetables, in particular sugar beets. Underground Ukraine has extensive mineral resources, notably iron ore and coal that is especially abundant in the eastern part of the country. The far western part of the country, which includes the Carpathian foothills of historic Galicia, has oil and natural gas reserves that were developed in the late nineteenth century, then seemingly exhausted by the second half of the twentieth century, and with new technology are about to be exploited once again in the early twenty-first century.

As one travels farther north, the open steppe gives way to a mixed forest zone of rolling hills and plateaus that are conducive to smaller-scale agriculture and dairy farming. It is only at the extreme edges of Ukraine’s territory that there are mountains: the Capathians in the far west, near the borders of Romania, Slovakia, and Poland; and the Crimean Mountains in the far south, along Crimea’s Black Sea coast. In modern times these small mountainous areas have become home to health resorts and have encouraged tourism, whether it takes the form of skiing and hiking in the Carpathians or restorative sanatoria and bathing in the mildly salty waters of the Black Sea at the foot of the Crimean Mountains.

The possibility for humans to exploit Ukraine’s natural wealth is in large part a function of its climate. Most of the country has moderate continental temperatures, which average +23º F/–5º C in January and +68º F/20º C in July. Adequate rainfall allows for an annual growing season of 205 days. It is also true that the steppe region is subject to hotter temperatures and dryer winds, which in the past have caused widespread steppe fires and periodic droughts that at times have resulted in famine and extensive loss of life.

Nevertheless, Ukraine’s physical geography has traditionally been quite favorable to human habitation. With hardly any real natural barriers (the Carpathians in the far west being the exception), a wide variety of peoples — both friendly and unfriendly — have for millennia had easy access to Ukraine. Its agricultural wealth has made Ukraine the “bread-basket” of whatever state ruled the area, allowing for extensive grain exports and, usually, an abundance of foodstuffs for human consumption. Finally, its mineral wealth has encouraged industrialization and allowed millions of the country’s inhabitants to find employment in the largely urban-based modern society that is Ukraine of today.

Human geography

Present-day Ukraine shares borders with seven countries: Russia and Belarus to the east and north; and Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Moldova to the west. In the south, Ukraine is washed by the waters of the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, beyond which is Romania, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

Like most countries, Ukraine is made up of several regions, some of which are quite distinct in terms of their geographic and cultural make-up. Historically, the most important of these regions have been Volhynia, Galicia, Podolia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia in the west; Chernihiv, Poltava, Sloboda Ukraine, and the Donbas in the east; and Zaporozhia, the Black Sea Lands, and Crimea in the south. Independent Ukraine is divided into twenty-four administrative entities called oblasts and one autonomous republic based in the Crimean peninsula. Although most of the historic regions no longer exist in any formal sense, awareness of their location is essential for understanding the historical past and cultural landscape of Ukraine.

Until the twentieth century, the vast majority of Ukraine’s inhabitants lived in rural areas. Cities, which were more like small towns with on average five to ten thousand inhabitants, had existed on the territory of Ukraine since pre-historic times. Of those that still exist today, the oldest find their roots in the medieval period and for the most part are in the north-central and western parts of the country: Kyiv (the capital), Chernihiv, and, moving westward, Lviv, Chernivtsi, and Uzhhorod. Farther west are three medieval cities, which, although outside the political boundaries of Ukraine, are located in territory inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians as well as in the past a significant number of Jews. These include Brest (formerly Brest-Litovsk) in present-day southwestern Belarus and Chełm/Kholm and Przemyśl/Peremyshl in present-day southeastern Poland. Of particular importance during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were several towns in western and central Ukraine (Nizhyn, Bratslav, Dubno, Ostroh, Slavuta, and Uman, among others), which were centers of flourishing markets that fostered both regional and international trade. Cities in the eastern and southern parts of Ukraine came into being somewhat later and were connected with the expansion of Russian imperial rule, whether in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (Kharkiv, Poltava) or the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (Katerynoslav/Dnipropetrovsk, Oleksandrivsk/Zaporizhzhya, Yuzivka/Donetsk, Mykolayiv, Odessa, and Simferopol).

Like many cities throughout central and eastern Europe, those in Ukraine were traditionally inhabited by peoples who, in terms of ethnicity, language, and religion, differed from the ethnic Ukrainians in the surrounding countryside. Whereas Jews eventually came to form a substantial proportion of the inhabitants in most towns and cities, especially in western and south-central Ukraine, the presence of other groups varied, depending on where a given city was located. Aside from Jews and a generally small percentage of ethnic Ukrainians, cities in the western regions of the country contained a substantial percentage of Romanians and Austro-Germans (in the case of Chernivtsi), of Poles and Armenians (in the case of Lviv), and of Hungarians (in the case of Uzhhorod); cities in the center and east included numerous Russians; and cities in the south had large populations of Russians, Greeks, and Crimean Tatars.

Ukraine’s ethnic diversity was not limited to its urban areas. Whereas present-day Ukraine is, like most European countries, a multi-ethnic state, the relative size of the country’s various peoples is significantly different than in earlier times, largely as a result of the demographic engineering — in the form of forced resettlement, starvation, and murder on a massive scale — that characterized much of the twentieth century. The result is that today, out of a population of about 48.5 million, by far the majority of inhabitants are ethnic Ukrainians (77.8 percent) and Russians (17.3 percent), followed in order of size by smaller numbers of Belarusans, Moldovans, Crimean Tatars, Bulgarians, Hungarians, Romanians, Poles, Jews, Armenians, and Greeks, all of whom together make up only 3.5 percent of Ukraine’s population.

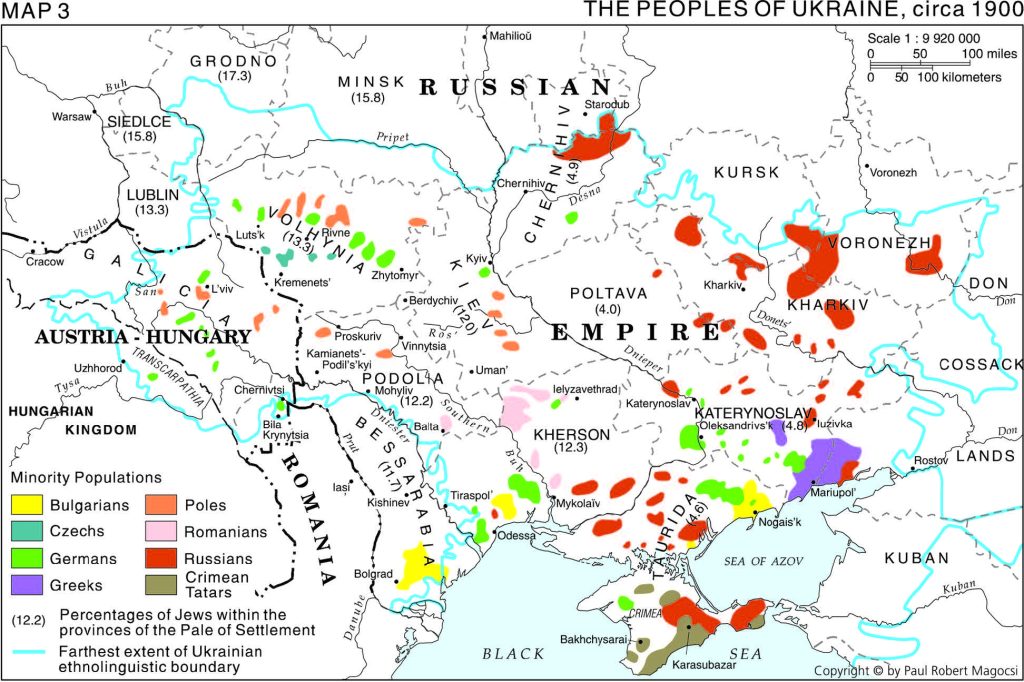

By contrast, the relative size of these various peoples was much different in the past. For instance, at the close of the nineteenth century, when the first comprehensive statistical data was being collected, the total number of inhabitants on the territory of present-day Ukraine was 30.6 million. In comparison with the present, about the year 1900 ethnic Ukrainians comprised a smaller proportion (72.4 percent) of the population, as did the Russians (9 percent), while the relative and in some cases absolute number of other groups was much higher than today: Jews (8.7 percent), Poles (4.2 percent), and Germans (2.1 percent).

The geographic distribution of these groups varied widely, with most Russians concentrated in the eastern and southern historic regions (Sloboda Ukraine, Donbas, Zaporozhia, Black Sea Lands, Crimea), Poles in the west (Galicia, Volhynia, Podolia), Germans and Romanians/Moldovans in the west and south (the former in Volhynia, Zaporozhia, Black Sea Lands; the latter in Bukovina, Podolia, Zaporozhia), and Greeks in the south (Black Sea Lands and Crimea). Certain groups were concentrated almost exclusively in one region, such as the Belarusans (in Chernihiv), Crimean Tatars (in Crimea), and Hungarians (in Transcarpathia).

With regard to Jews, their geographic distribution also varied. At the dawn of the twentieth century (1897/1900), the vast majority of the 2.6 million living on the territory of present-day Ukraine were found in its central, eastern, and southern regions. Those regions, which were located in the Russian Empire, were part of an area known at the time as the Pale of Jewish Settlement, that is, lands west of the Dnieper River, which had until the 1790s belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Of the nearly two million Jews living in the Pale of Settlement, the largest proportion in Ukrainian lands were in the tsarist provinces of Volhynia (13.3 percent), Kiev (12 percent), Podolia (12.2 percent), and Kherson (12.3 percent), the administratively distinct metropolitan district of Odessa (30.8 percent), and the neighboring province of Bessarabia (11.7 percent), which today is part of both independent Moldova and Ukraine. Of the 681,000 Jews living at that time in present-day Ukrainian territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, by far the largest proportion was in East Galicia (79.1 percent), followed by Transcarpathia (11.2 percent) and Bukovina (9.6 percent) — see map 13.

The demographic situation today is radically different. As a result of the tragic events of the twentieth century — including artificial famine, two world wars, the Holocaust, and most recently, post-Communist economic disparities — the total population of Ukraine is on the decline. The number of ethnic Ukrainians has remained stagnant at about 37.5 million, while the number of Jews has dramatically decreased in comparison to what it was at the beginning of the twentieth century. Today their number stands at 84,000, only 0.2 percent of Ukraine’s population. Most live primarily in cities, with the largest concentrations in Kyiv, Odessa, Dnipropetrovsk, and Kharkiv.

Click here for a pdf of the entire book.