Dr. Diana Dumitru: No direct evidence yet of Stalin's planned deportation of the Jews

What are the causes of postwar antisemitism in the USSR, how was cosmopolitanism combated on the ground, and is the theory about the deportation of Jews to the Far East in 1953 justified? These are some of the many questions raised in the following interview with Dr. Diana Dumitru, guest lecturer at the master’s program in Jewish Studies at NaUKMA and associate professor of Chișinău State Pedagogical University.

In the Jewish milieu there is a myth about the absence of antisemitism in the 1930s. To what extent is this statement justified?

Jews whose formative years coincided with this period recalled how they entered universities easily, obtained Stalinist scholarship, worked in various institutions, and the like. Of course, these recollections are not unsubstantiated, but one cannot speak about an atmosphere of victorious internationalism.

Sources indicate that antisemitism had not disappeared; it was simply that the state was harshly suppressing its manifestations. I once came across an OGPU report from the late 1920s. Two employees of the Odesa morgue are nostalgically recalling the 1905 pogrom in Kyiv, as the agent emphasizes, savoring the details; like, it would be great to go and carve up the Jews, but the time is not right. At the same time, the state tried to combat enrooted antisemitic stereotypes and to cultivate a positive image of the Jews among the population. As a result of these efforts, Jews gradually began to be perceived as “normal” Soviet citizens. After two decades of Soviet rule, the nationality question was extremely peripheral to the new generation.

How can one characterize the Soviets’ information policy during the Holocaust—as the deliberate concealment of the Catastrophe out of fear of Nazi propaganda, which had imposed the stereotype of “Judeo-Communism”?

The latest research, Karel Berkhoff’s, for example, refutes the myth that there was no information in the Soviet press about the crimes committed against the Jews. There was information—clear and unequivocal—in the central newspapers, specifically about the destruction of the Jews, not some abstract civilian population. For example, in August 1941 Pravda and Izvestiia published a speech by Solomon Mikhoels in which he stated openly that Hitler was intent on exterminating the entire Jewish people. In September 1943 [Ilya] Ehrenburg wrote in Krasnaia Zvezda that Jews from various countries had been gathered in Minsk, and they were all killed, and in April 1944 Pravda noted that there were no Jews left in Kyiv, Prague, Warsaw, and Amsterdam. In December 1944 that same newspaper reported the number of Jews who had been destroyed in Europe: six million.

Of course, the Soviet government was vulnerable, especially in the new Soviet territories. In western Ukraine, Bessarabia, and the Baltic region, local residents equated Jews with Bolsheviks. Grasping the entire complexity of the situation, the regime tried not to focus on the “Jewish question” during the war. At the same time, Soviet Jews were following the official discourse attentively and reacted badly to any attempts to ignore Jewish identity, both as heroes and victims. It is difficult to say how successful Nazi propaganda was in inciting antisemitism, but it definitely succeeded in placing the “Jewish question” on the agenda. Even Soviet people who were not considered antisemites had a possible explanation for certain problems…

Meanwhile, after the war the authorities were very serious about manifestations of antisemitism. I know of a dozen cases in Moldova that resulted in convictions for statements like “in our republic only Jews and communists live well.” Such revelations ended badly in 1948 and 1950, even when the Jews found themselves under attack by Moscow.

The growth of antisemitism in late 1945 was recorded in various European countries: in France and Germany, Poland and the USSR. What were the reasons behind this in the Soviet Union, especially in the new territories that were annexed in 1939–40?

In Moldova, for example, there were two kinds of antisemitism: the traditional, prewar kind; and a new, Soviet-style one. The point is that Sovietization led to an influx of new cadres, the majority of whom were not Moldovans. There is a multitude of reasons for this: doubts about the loyalty of the local population; poor command of the Russian language; and, on the whole, the level of illiteracy among Moldovans (in 1930 it was 61 percent). It is not surprising that many Jews, both locals and newcomers, ended up in key positions. There was talk of Soviet power being Jewish power.

A stream of antisemitic letters began flooding in. In one of them, addressed to Stalin, the anonymous author complains about the national policies that turned Moldova into a republic with “Jewish dominance.” Apparently, it was written by an intellectual because he mentions that a Moldovan play usually does not even attract ten spectators, but if there is a “Jewish” performance, there is no hall in Chișinău that could accommodate everyone.

Everybody was blamed, one after another. For example, a stream of letters was directed at Koval, first secretary of the Central Committee of Moldova, who was married to a Jewish woman. The denunciations note that Sofia Koval “feels like a queen and is implanting Jews; wherever you look, Jews have become ensconced and are bringing home everything to their queen.” There were complaints that Jews walk around “in exquisite silks, wool, fashionable shoes (“they have won”), while Moldovans are ragged, barefoot, hungry.” That’s Soviet (read: Jewish) impartiality, it was said. All this continued until Moscow made it clear that all of Koval’s wife’s connections and her background had been checked and rechecked and that no further requests would be considered.

After 1948 political antisemitism, triggered by the proclamation of the State of Israel, appeared in the USSR. The meeting that 50,000 Jews organized for Golda Meir in a Moscow synagogue was a shock to Stalin; he realized that the Jews might have an alternative loyalty. This might be likened to the fury of a jealous husband who does not want to share his wife with anyone. Moreover, in the context of the Cold War and Israel’s accession to the Western bloc, the leader and his entourage become infected with spy mania and political distrust of the Jews—they see the world through this filter.

And on this is superimposed the everyday antisemitism of the masses…

The roots of hostility toward Jews were diverse. For example, one of the main problems in the postwar years was housing. When Jewish survivors returned to their apartments, they could hear from the new tenants things like, “Too bad you weren’t all killed…” On the one hand, there was the influence of Nazi propaganda—people were no longer ashamed of antisemitism; on the other, they were ready to pounce on anyone who encroached on “their” home, whether a Jew, a Russian, a Ukrainian, or a Moldovan.

I have seen a document in which the Deputy Minister of Health of the Moldovan SSR, by the name of Gekhtman, requests that he be released from his duties because of his inadequate housing situation; he was living in a tiny apartment without a bath with his two children and 70-year-old mother. What can be said about ordinary citizens…

It is 1944. A Jewish war veteran writes to Stalin from the front about how SMERSH officers tried to evict his wife and children from their apartment. They were shouting that his wife had taken those Jewish children from an orphanage, in order to obtain benefits for a large family. And along the way, they accused her of obtaining the Order of the Red Star by sleeping with someone. You think they believed that nonsense? Of course not. It was just that there was very little suitable housing, and all means were used in the struggle for it.

How did the authorities react to such excesses?

In various ways. I've read cases of bullying. But I’ve also seen an Agitprop document summarizing the gist of the issue. Yes, it admits that anti-Jewish sentiment increased because of the influence of Nazi propaganda during the war, but it also emphasizes that after the Catastrophe, Jews tend to exaggerate antisemitism. The authorities think that the problem is not as terrible as the Jews imagine it to be.

It is clear that in those years the situation has reached the boiling point. In the former archives of the CPSU there is a record of a summons issued to a Jew ordering him to come to the Central Committee because of conversations about the condoning of antisemitism. He went, confirmed that the problem exists, and declared that if the government doesn’t change its attitude to it, he will commit suicide.

In the fall of 1945, a housing crisis nearly caused a Jewish pogrom…

Yes, Jewish survivors returning to their apartment now occupied by another family—that’s a typical incident. But it was not very typical when, at the demand of the previous tenants, a Ukrainian family was forced to leave, after which one of its members, a Red Army soldier (who happened to be home on a brief furlough), got drunk and, together with a friend, beat up an NKGB lieutenant named Rozenshtein, who was in the vicinity. The latter could not stomach the offense, went home, put on his uniform, and grabbed his TT pistol, after which he returned to the home of his assailants, and laid both men out. The tribunal sentenced the lieutenant to be shot, but Kyiv was already in the grip of pogromist moods. During the funeral procession several Jewish passersby were beaten up.

A letter written by four war veterans—Kyivan Jews—to Stalin, Beria, and Pospelov, the editor of Pravda, is interesting in this connection. The tone of the letter is very sharp; the authors directly accuse the Ukrainian authorities of conniving at antisemitism and compare their stance with the course that “came earlier from Goebbels’s office, the worthy successors of which turned out to be the CC CP(B)U and the SNK [Council of People’s Commissars] of the Ukrainian SSR. The signatories threaten, saying that the Jewish people are “availing themselves of every opportunity to defend their rights, all the way to an appeal to the International Tribunal.”

The letter is not anonymous and demonstrates that it is difficult to intimidate people who address Stalin this way; this was a new brand of Jew.

In general, the war loosened the reins not only for antisemites. Here is a typical example. In the early morning hours of 10 May 1945 Aleksei Shcherbakov, head of the International Information Department of the CC AUCP(B), died in Moscow. The editorial boards of the major newspapers dispatched their correspondents to cover the funeral. Some Jewish journalists from the All-Union Radio Committee refused [the assignment]. I saw this internal correspondence. One of them said outrightly that the deceased had been an antisemite, two others pleaded weak nerves. They were reprimanded for refusing to carry out their assignment.

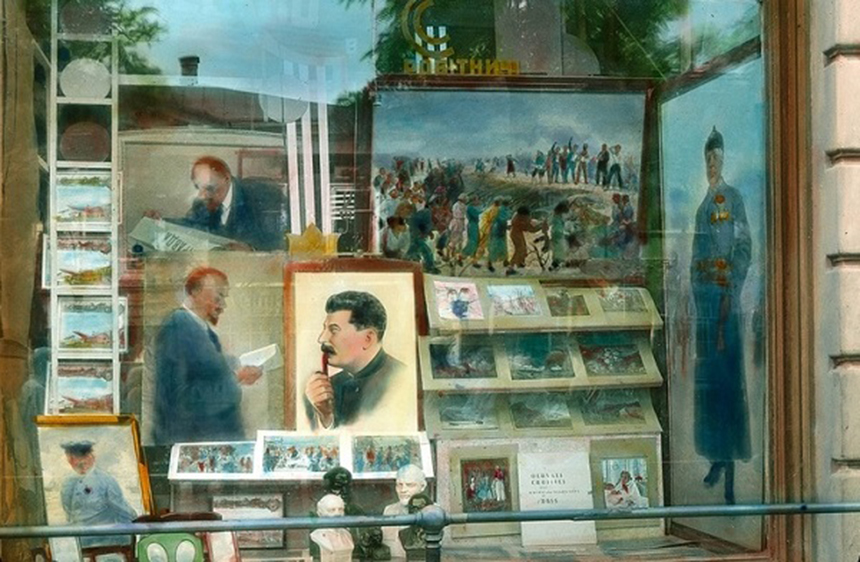

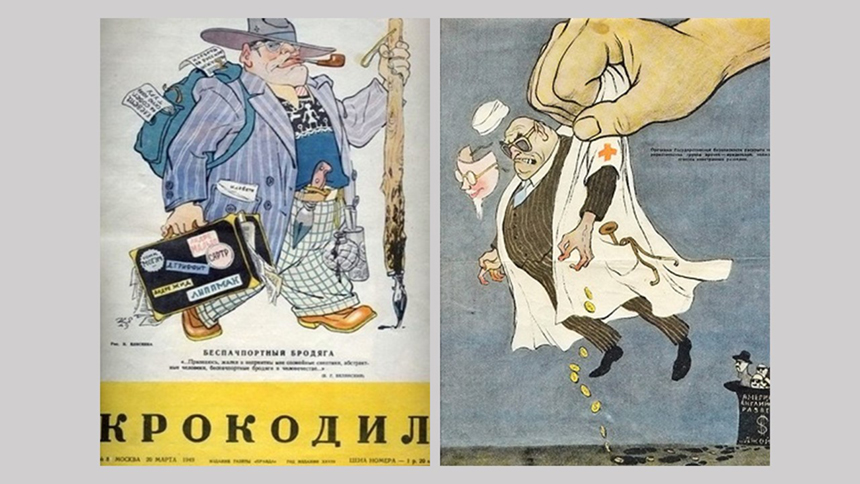

In 1948 the so-called struggle against cosmopolitanism was launched in the country. Is this in principle a Jewish story or did Jews simply end up as scapegoats in the fight against adulation of the West?

That is an excellent question, for which historians offer various answers. Studying documents, I see how vague the directives from the center were. That is why local leaders tried to guess what it was all about and whom they were supposed to struggle against specifically. Many decided that the Jews fit the definition of cosmopolitans in all respects, while others, who were more cautious, sought to avoid openly antisemitic accents.

To this day we do not know exactly what the government wanted to achieve; the only clear thing is that it was irked by comparisons with the West, which were not in the USSR’s favor. The authorities were displeased that millions of Soviet people during the war had seen the high living standards in the West with their very own eyes, and they tried to nip these sentiments in the bud.

Then why did the campaign take on a Jewish tinge, rather than an Estonian or Lithuanian one. After all, in these new republics, comparisons with “before” simply begged to be made.

A struggle was waged against nostalgia for the previous regimes in the new territories, not just in the Baltic region. And they imprisoned people who recalled that life was better under the Poles/Romanians or the independent government of Estonia or Lithuania. For example, a Jew from Bessarabia named Saul Goldshtein was sentenced to ten years for saying that “life was better under the Romanians than in the USSR…here, even doctors and engineers walk around coatless and in canvas shoes in 20-degree weather.” This comparison cost him dearly.

As regards the Jewish tinge, it was no accident. If we examine the social profiles of people with higher education, for example in Bessarabia, many of them turn out to be Jews. Many local physicians studied in Italy, France, and Belgium simply because in Romania in the 1930s a Jew could not obtain a medical education easily. They were fluent in several foreign languages, had lived in the West for some years, and had seen a different world. They could easily be called cosmopolitans in the direct meaning of this word. Meanwhile, the preponderant majority of Moldovans did not perform this role.

Obviously, in the collective conscious, many Jews were perceived as not being quite Soviet people, but the extermination of the Jewish intelligentsia began with the top ranks of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which was thoroughly Soviet and devoted to Stalin. What was this: paranoia on the part of the aging dictator or a pragmatic step in the spirit of Great Processes, when Stalin clearly understood whom he was destroying and why?

Perhaps the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee made a strategic mistake when they decided to maintain the Committee’s influence even after the war. They thought they would become the spokesmen of the interests of Soviet Jewry, failing to understand that the need for them had already disappeared.

Furthermore, they submitted a request for the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee to be removed from the jurisdiction of Agitprop and report directly to the CC. Through Polina Zhemchuzhina, they transmit a letter criticizing the Birobidzhan project and take other political steps that a few years hence will take on a dangerous coloration. Solomon Lozovsky, a member of the CC AUCP(B) and one of the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, tries to explain the importance of the Committee, with its ties to most foreign heads of government and the world’s financial and business elite. In April 1945 this sounds not too bad, but in late 1948 that’s tantamount to admitting to a crime. All of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee’s previous experience, including Mikhoels’s many-months-long trip to the U.S. and Canada, looks like a guilty verdict now.

The last period of Stalin’s life was the “Doctors’ Plot.” Was this an irrational move by the elderly leader or was he playing some sort of game, whose goals are not known to us?

Perhaps Stalin, overcome by his phobias, did not take kindly to the advice of his doctor, Vinogradov, “to rest.” He might have taken it as a call to retire, to withdraw from public affairs, and he saw the doctors as a tool for removing him from power. When we talk about whether he believed in a conspiracy, we are on very shaky ground. For a normal person, it is difficult to see sense in this.

How likely is the theory about the planned deportation of the Jews?

So far there is no direct evidence; we see it as a rumor and a reflection of the public mood. Jews were paralyzed with fear; that’s a fact. But stories about someone spotting train cars standing on a siding are not documents.

As for moods, they dovetail perfectly with the logic of that era. Literally that same year, after Stalin’s death, [Lavrenty] Beria began to promote the policy of korenizatsiia [indigenization] in Latvia in the style of the 1920s. An order was given to replace Russian Latvians in leadership positions, and rumors instantly began to spread about the upcoming deportation of all Russians from Latvia! The Soviet people perceived reality this way: They knew that deportation was one of the methods of collective punishment, so they were ready for it.

So, the deportation of Jews to the Far East is one of several possible scenarios; nevertheless, it has not been confirmed. But time is unpredictable. For a long time, the Soviet Union disavowed both the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the Katyn tragedy, but in the end the relevant documents were found…

Interview by Mikhail Gold

Originally appeared in Russian @ Хадашот.

Translated from the Russian by Marta D. Olynyk.

Edited by Peter Bejger.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.