Professor Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern on Ukrainian-Jewish Encounters

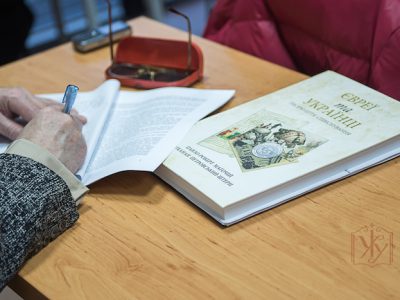

Dr. Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, co-author of “Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence” has over the last several months lectured in Europe and taught in Ukraine about Ukrainian-Jewish relations. The following are questions provided to the academic by Ukrainian Jewish Encounter before he returns to the classroom at summer’s end. Dr. Petrovsky-Shtern is the Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Northwestern University and is a member of UJE’s Academic Council.

Ethnic Ukrainians have lived side-by-side with different nationalities over the centuries. What makes the Ukrainian-Jewish relationship so special? Why should anyone care about this particular relationship?

There are several ways to answer this question. The answer depends with whom you are speaking.

If this is a university student, say: “Jews made Ukrainian villages into towns. Jews integrated Ukraine economically into Europe three hundred years before the EU came into being. Jews such as Ze’ev Jabotinsky shaped the mentality of leading Ukrainian national-democratic thinkers. And Ukraine was home to the biggest Jewish community in Europe. To appreciate this, we need to study Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Such study helps us to better and more deeply understand Ukraine.”

If this is a random yet curious person, say: “It is impossible to understand Ukrainian history and culture without the role of the Jews. East European Jewish history and culture is inconceivable without Ukrainians and Ukrainian culture and history.”

If this is a person who seems to reject the Ukrainian-Jewish link to begin with, say: “If you’d like to understand who you are, and only if you really want to, you should ask who your people have been living together with—for at least a thousand years—and how and why they lived together.”

What are the most common stereotypes your audiences and students have voiced about Ukrainians and Jews and how did you respond to those stereotypes?

I am enormously grateful to the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter for giving me an opportunity to teach in Ostroh, Dnipro, Munich, and Lviv. I was learning new things and mastering new methods at every site. After my first class at the Ostroh Academy, a seventeen-year-old female freshman, implying the Ukrainians, asked a question: “Why do they still not like the Jews?” It was a shock for me and for the audience of about thirty-five students and professors. I asked her, “Who are they? You are here to learn something about Jews, correct? So, it is ‘they’ minus one. Now, we have another thirty-plus people in the room eager to learn about Jews and Ukrainians. So, it is ‘they’ minus thirty-plus. The first printing of the book Jews and Ukrainians: A Millennium of Co-Existence is exhausted. About a thousand readers wanted to learn new things about that subject matter. So, now, it is ‘they’ minus a thousand.”

The girl then answered: “Well, in my family… my parents… in my village…”

I replied: “But you are taking this course on a voluntary basis! Nobody forces you to take it. Which means you make a difference. And you have a good chance to change what ‘they’—your parents—think or feel. Tell them about what you learn here. Your enthusiasm for the subject matter will shatter their bias.”

What has surprised you the most in your lectures and teaching about the people you've interacted with vis-a-vis the Ukrainian-Jewish relationship? Is there a difference in the understanding of this relationship in the various countries you've been to, and what are those differences?

People in the United States and Canada think they know the basics and ask sharp questions about the Ukrainian-Jewish grand historical narrative, in which pogroms, migrations, and antisemitism dominate. Jews and Ukrainians in North America quite often just need a reminder of the Russian imperial context, the meanings of the Nazi Germany occupation of Ukraine, and of Soviet xenophobic imperialism to figure out how to overcome their bias. These people need to reconsider and modify what they already know.

Students in Ukraine don’t know the basics. Born around the early 1990’s, they learned a Ukrainian history that was only about ethnic Ukrainians. These students learned that some Jews lived in Ukraine and were killed by the Nazis—that’s it. They have no idea who these Jews were, how they ended up in Ukraine, and why they stayed. For such students the discovery of any Jewish role in the Ukrainian economy, politics, culture, music, arts, and literature is astounding. They are thirsty for basic knowledge that influences the way they think and understand themselves and their native land. For them, the discussion of Jews and Ukrainians is an eye-opening intellectual experience. It is the first serious opportunity to study the Other as a neighbor, not as an enemy alien.

What have you learned about the relationship from your travels and teaching in the past several months? Has your opinion changed on certain aspects of the relationship and if so, how? And if not, why not?

I understood that the Jewish-Ukrainian relationship couldn’t be a mantra we preach. Rather, it should be a mantra we question, revise, and teach. What were the problems that triggered the catastrophes for both peoples? What where the productive cross-fertilizing aspects of this relationship? Why did Ukrainians and Jews start to move out from Ukraine to the New World at the same time? Why are both Ukrainian and Jewish intellectuals national-democratic thinking people, whereas most ordinary Jews and Ukrainians share the principles of Homo Sovieticus thinking? The best way to question what we do at the UJE is to give the audience some basic primary sources and let people of any age and study experience discuss these documents. We should be instrumental in helping them think. The ensuing intellectual exchange builds better bridges than any one-time lecture. We show thus that we are not a politically biased group of people. On the contrary, we are ready to question our premises and create new visions together with those who come to learn with us. By us I mean not only Paul Robert Magocsi and myself, but the entire extended UJE team.

What is the single most important thing that Jews and Ukrainians have to learn from one another? What is their biggest misconception of each other?

Many Jews still think that all Ukrainians are the same and that they are antisemites. Some Ukrainians think that all Jews are the same and they are Ukrainophobes. The most single important thing both people should learn about one another is that, first, there are many more things the two people share than they don’t, and second, that neither Ukrainians nor Jews are homogenous people. It is crucial to discard Soviet and post-Soviet style xenophobic generalizations. Difference matters; it teaches tolerance within the ethnic group and beyond it. Without this newly mastered tolerance this generation of Ukrainians would not be able to become part of Europe.

Some have argued that now is not the time to raise painful chapters in the history of Ukrainian-Jewish relations since Ukraine is in a state of war and Israel is facing its own problems internally and externally. Some say that doing so will only create an antagonism and actually create barriers to understanding so it's better that these questions be discussed at another time. Where do you stand on this issue?

Only a people with a slave mentality are afraid of painful issues. Freedom starts when a nation is ready to discuss the most difficult chapters of its own history. Particularly because such discussion means responsibility, which a group with a slave mentality does not want to deal with. Yes, it is time to raise painful chapters in Ukrainian-Jewish relations and assume responsibility for them in the most forceful manner.

Much emphasis has been given to the painful topics in Ukrainian-Jewish relations. Why do we not speak more about the positive chapters in the relationship? The territory of contemporary Ukraine after all was the birthplace of some of the great Jewish minds and of Hasidism. This would it have been impossible if an atmosphere of tolerance did not exist there.

Early modern and modern Ukraine was neither multicultural nor tolerant, since both notions are relatively recent and convey modern-day phenomena. Yet Ukraine has always been multiethnic and its ethnicities coexisted in productive relations, albeit they occupied different sociocultural and economic levels. But it was precisely that fruitful socioeconomic balance that allowed Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians to build churches, cathedrals, and synagogues, trade in the shtetl marketplace, share food recipes, ornaments, tales, and songs, and freely borrow from one another forms of thinking and modes of behavior. Such Jewish writers as S.Y. Agnon, Sholem Aleichem, and Vasily Grossman are impossible without Ukrainian characters, while such Ukrainians as Ivan Franko, Ivan Bahrianyi, Yuriy Kosach, and Oleksandr Irvanets are impossible without their Jewish images. Of course, the Hasidic movement was an early modern pietistic movement of religious revival born and developed in the Ukrainian lands. Its folklore tales, parables, and songs bear an indelible imprint of the Ukrainian folk culture.

What do we not know about the relationship, but should know?

The study of that relationship allows Ukrainians to revisit their post-Soviet vision of Ukraine as a country with an exclusively Ukrainian ethnic history and culture. It opens up wonderful intellectual opportunities to see Ukraine as historically multiethnic and build the future of Ukraine as multicultural. It allows Ukrainians and Ukrainian Jews to think differently about who they are as a people.

The same should have happened to the Israeli Jews who have Ukrainian roots. They should have appreciated various opportunities to get beyond the received wisdom. Yet this did not happen. Israeli academia has few experts on Ukraine (actually there are three, and all three are part-timers) and the Israeli establishment, by and large pro-Russian, resists any new knowledge that challenges its received academic wisdom. A Hebrew-language version of Jews and Ukrainians would significantly help change the situation, but so far Israeli publishers have not welcomed the book.

(Photos are courtesy of the professor.)

(In Ukrainian).